Voices from the Dark Years (24 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

N

OTES

1.

P. Webster,

Pétain’s Crime

(London: Pan, 2001), p. 88.

2.

Burrin,

Living with Defeat

, p. 420.

3.

Ibid., p. 28.

4.

Pechanski,

Collaboration and Resistance

, p. 39.

5.

Amouroux,

La Vie

, Vol. 1, pp. 85–6.

6.

Interviewed in Pryce-Jones,

Paris

, p. 250.

7.

Ibid., p. 94.

8.

No single source is available. The figures given are from historian Robert Aron and L’Institut National de la Statistique.

9.

Burrin,

Living with Defeat

, pp. 264–7.

10.

Ibid., p. 273.

11.

Ibid., p. 373.

12.

Chronique de la France et des Français

(Paris: Éditions Legrand, 1987), p. 1,107.

13.

Quoted in Burrin,

Living with Defeat

, p. 75.

14.

Ragache,

La Vie des Ecrivains

, p. 64.

15.

Kernan,

France

, p. 26.

16.

Laval,

Unpublished Diary

, pp. 86–7.

11

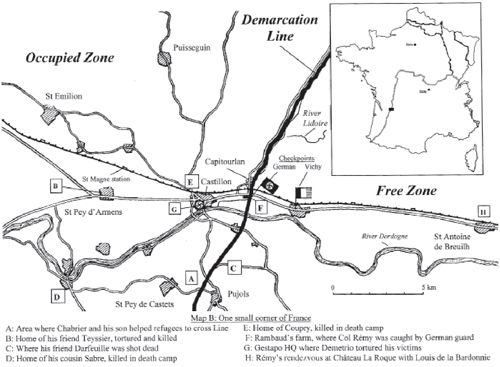

While the intellectuals talked, the politicians manoeuvred and the businessmen schemed, a number of ordinary people living less than 15km from the author’s house in south-west France decided independently of each other to do what they could to keep the fluttering flame of freedom from being extinguished altogether.

Georges Chabrier returned home to St-Pey-de-Castets after being demobilised in Pau to find that his home was 300m on the wrong side of the Demarcation Line. Volunteering underage in the First World War, he was twice wounded during three years at the front. Demobilised in 1918 aged 20 and with a leg troubled for the rest of his life by pieces of German shrapnel, his respect for authority survived the hardships of the 1920s and 1930s. Called up again in 1940, he served with a unit of other wounded veterans in Pau until demobbed at the Armistice. Believing that the marshal had saved his life at Verdun, Chabrier supported him as legal head of state, but nevertheless decided that his duties as a patriotic French citizen were not yet discharged, whatever the generals and politicians had decided.

Picking up the pieces of his peacetime life, he spent weekday mornings as an auxiliary postman; in the afternoons he worked as a carpenter and the local road-sweeper and school caretaker. Collecting the mail from the nearby town of Castillon, where it arrived by train, he cycled back with it to the village of Pujols, where there was a sub post office inside the thirteenth-century castle built there on the orders of England’s King John I. After the incoming mail had been sorted, Chabrier set off on his bicycle again with his bag of letters in order to deliver them.

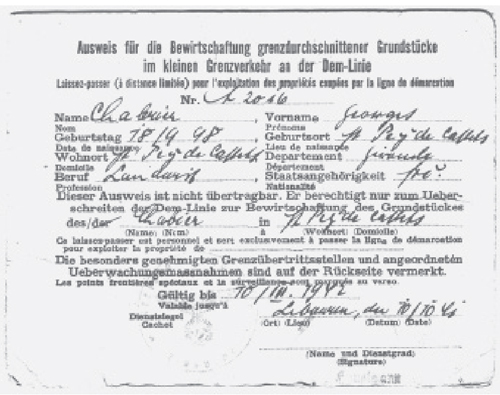

St-Pey and Castillon were in the Occupied Zone, Pujols in the Free Zone, so Chabrier had a pass from the local Kommandantur entitling him to cross the line at any time between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. The first risk he took was to carry across the line letters slipped inside the wrappers of rolled-up magazines for ex-servicemen whom he knew. Most covered family matters too complicated or too intimate for the official printed postcards; others were business correspondence that the writers did not want seen by German censors. If caught, the routine penalty for this was seven days in prison, and two weeks for a second offence but, had any of the letters contained military information, the penalty would have been a firing squad or deportation to a concentration camp.

For a man with a wife and children, whom he was also putting at risk, to take this decision required a very steadfast kind of courage. Twice Chabrier was denounced: on the first occasion, the guards searching him did not think to look inside the magazine wrappers; on the second occasion, the Germans arrived to search his carpentry workshop while he was having his hair cut by the village barber. Luckily, a neighbour secreted the post-bag with a bundle of clandestine mail in a deep pile of wood shavings. The Alsatian sniffer dog sneezed several times at the pungent resin in the pitch-pine shavings, but his handler did not think of digging into the pile. Later, Chabrier told a fellow

résistant

: ‘The Germans searched everywhere in the house and the barn. They took away all the letters I had written my wife while in uniform, and kept them two weeks before telling me I could have them back. By God, I was frightened that time!’

George Chabrier’s pass to cross the Demarcation Line.

Running the village telephone cabin and cooking lunch for sixty-three pupils in the village school, his wife looked after him and their two sons. She was soon pregnant again, but the couple had to move out of their bedroom into the spare room when two German soldiers patrolling the line were billeted on them. One of the lodgers was the driver of the Oberleutnant who had signed Chabrier’s

Ausweis

. Having been a German teacher in Paris before the war, this officer spoke excellent French, confessing to his involuntary hosts with a conspiratorial wink that he hoped one day to join his wife and children in America. Judging that his consistent under-performance in the Wehrmacht made him a likely candidate for the eastern front after the launch of Operation Barbarossa, he drove the car into the Free Zone one day and was never heard of again.

With two less amenable Wehrmacht men sleeping in the house every night, Chabrier’s next step was even more courageous. Although bona fide refugees were allowed to return home in the summer of 1940, once the controls were tightened up there were many thousands of people who wanted to cross illicitly. The risk of being caught was high and only local inhabitants knew when the mobile patrols were likely to pass a given point, so Chabrier quietly informed his ex-service friends that he was prepared to help people who needed to cross without papers.

French gendarmes and SS troops checked the identity of all passengers alighting at Castillon station because it was the last stop before the frontier. Line-crossers, therefore, left the train at the previous stop, St-Magne, leaving their bags on the train. Railway staff turned a blind eye when Chabrier’s 15-year-old elder son arrived at Castillon station to load the luggage onto his father’s cart pulled by an aged mare and brought them home, where they were hidden until nightfall. While the two Germans slept in the main bedroom, he then reharnessed the mare and drove the luggage quietly through the curfew to a bridge over the stream that ran along the line. There, he loosed the family’s ancient sheepdog to cast about sniffing for anyone nearby. Since the guards had orders to shoot to kill, it was only when the dog was satisfied there was no one around that the boy carried the bags across and hid them on the other side.

Map of the Castillon area.

His father meanwhile rendezvoused with his friends bringing the refugees and led them across the line between patrols. They collected their luggage – sometimes far too much of it – and followed him up to Pujols on its hill, where he discreetly left them with the local café owner before retracing the dangerous route homewards to snatch a few hours’ sleep before dawn.

No one kept a record of how many people father and son helped in this way. All Chabrier would say was that they included women with babies and children, escaped POWs and even an English colonel. Usually, he was warned to expect a group by the Mayor of Libourne or the Procureur de la République, a sort of district prosecutor. Having belonged to no organised group, neither they nor Chabrier received any medals or commendations after the Liberation; nor did he or his elder son ever talk about what they had done.

As to why so many people wanted to cross into the Free Zone, where they were still far from safe, a large part of the reason was simply ignorance of conditions there, due to the unavailability of Vichy newspapers in the Occupied Zone and the frequent attacks on Pétain in the German-controlled press in Paris, which made life in the Free Zone seem attractive. In a sense it was preferable: Simone de Beauvoir noted on a visit to the Free Zone in 1941 the availability of foreign newspapers and American films no longer available in Paris.

1

For immigrants at risk there was also a powerful magnet at Vichy in the presence of US and other neutral diplomatic missions, from whom a visa might be forthcoming.

On one occasion an attractive and well-dressed woman in her mid-30s with a Parisian accent arrived at Chabrier’s house out of the blue carrying a small suitcase and saying that she worked in the War Ministry and needed to cross the line, but had lost her papers. With his wife still in bed after the birth of their third child, Chabrier played the part of a stupid peasant, ignoring the woman’s show of distress and explaining that all she had to do was go to the German Kommandantur and ask them for a duplicate pass. His instinct was proved right a couple of weeks later when she was seen in uniform at the check-point in nearby Capitourlan, strip-searching women crossing the line there.

Had Chabrier needed any reminder of the penalties for the risks he ran, it came when an old service comrade named Teyssier, living a few kilometres to the north of St-Pey, was caught, tortured and returned dead to his family. His cousin Sabre, who was the butcher in another neighbouring village, died in a death camp crematorium – as did Coupry, another friend caught in August 1944 taking people across. A fourth friend, Darfeuille, was taking some documents across when shot dead by the guards several hundred metres inside the Free Zone.

Some were just unlucky, but who betrayed the others? Chabrier answered:

It wasn’t just the vigilance of the guards and German customs officers. Other

passeurs

who worked for profit – ten francs for a letter and as much as 10,000 francs for taking a person across – denounced those of us who did it for free. Nobody will ever know how many bodies of rich Jews who had been carrying all their wealth with them were fished out of the Lidoire [a tributary of the Dordogne, along which the Line ran] after being killed by these people.

2