Voices from the Dark Years (44 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

On 5 June 1943 Laval announced the departure of another 220,000 young men including agricultural labourers to Germany, resulting in widespread comments that the Germans were going to bleed France white by taking all its young men. Yet even this did not pacify Fritz Sauckel, who reported to Hitler on 9 August:

I have completely lost belief in the honest goodwill of French Prime Minister Laval. His refusal to execute a further programme for recruiting 500,000 French workers to go to Germany before the end of 1943 amounts to downright sabotage of the German struggle for life against Bolshevism.

11

Although exempt from the STO because employed as a Paris fireman, Raymond Bredèche decided to go absent without leave while he still had the chance, despite this making him technically a deserter from the armed forces. With a compass and rucksack of warm clothing and food, he took a train to Grenoble and simply walked into the countryside until challenged by a sentinel at the approach to a Maquis camp. For him, it was as simple as that. Whatever his dreams of glory, the reality was hard. The group had no weapons until an Italian unit withdrawing over the Col de Muzelle in September dumped three crates of ammunition, handkerchiefs, socks and two rifles. Only then could the band of young men pretend that they were fighters.

12

Their diet was mainly potatoes bought from local peasants, who would have preferred to sell their surplus to the black market at higher prices. It was a feast when Bredèche killed a 1m-long

couleuvre

snake and roasted it over a fire. Maquis ‘wages’ did not run to restaurant meals: camp leaders received 20 francs a day; ‘NCOs’ had from 9 to 15 francs; the other men got 5! Even this money had to be stolen from railway stations, post offices or houses of suspected collaborators or black marketeers. As late as five months before D-Day, one Maquis unit in Dordogne had only three Sten guns with ninety-two rounds of ammunition, seven revolvers and twenty-three rifles. Another group further north had three Sten guns, six grenades, thirty-five revolvers and thirteen rifles between them.

In most Maquis units, Reveille was at 6.30 a.m., followed by toilet and breakfast. The salute to the flag, if observed, was rarely accompanied by a bugle call, more often by accordion or mouth-organ. Cleaning camp and other chores occupied the rest of the morning; obtaining food much of the afternoon. Often, foraging turned to robbery – the Chantiers and Compagnons camps were targets of choice to get winter clothing and boots. One unit in the Ardennes hijacked mail bags containing several villages’ food tickets and then went on to steal 150kg of government tobacco next day.

On 25 July Mussolini was overthrown after the Allied invasion of Sicily. During the resulting confusion, General Lospinoso managed to illicitly acquire the Gestapo’s list of Jews registered in Italian-occupied territory, and hastened back to Italy to organise a gigantic rescue operation – as Bastianini had done in Dalmatia. With the SS hard on his heels, he set up a complicated operation to ship all the refugees at risk to North Africa, with American help. Arrangements were made to move 30,000 men, women and children.

13

On 8 September the scheme’s banker Angelo Donati was finalising the details in Rome when Eisenhower’s HQ prematurely released the news of the Italian surrender. With the Germans immediately occupying Nice, it seemed that the rescue plan had failed.

Particularly at risk were up to 527 children hidden short- or long-term in convents and elsewhere by Odette Rodenstock and Moussa Abbadi. To keep in touch with them and bring letters from parents, Odette travelled day after day on

gazogène

-powered buses to visit foster-parents – all too often finding them at the end of their tether, not just because they were risking their lives but because the small child they had welcomed into their home would say nothing to them but, ‘I want my Mummy. I want my Mummy.’ Older children caused different problems. Unable to resist divulging a secret, a boy might tell a classmate, ‘My name isn’t really Rocher. It’s Reichmann, but you mustn’t tell anyone.’

14

In August 1943, while the famous Parisian boys’ choir Les Petits Chanteurs à la Croix de Bois were singing in Berlin, the insanity of the Final Solution saw eighty-seven detainees transported

westwards

from Auschwitz through Poland and Germany to Alsace. Dr Josef Hirt, director of the Institute of Racial Anthropology at Strasbourg University, wanted freshly killed Jewish bodies undamaged by bullet wounds or ill treatment for his experiments. These unfortunates were thus to be gassed in a specially adapted gas chamber at Natzwiller. Although not a death camp designed for mass slaughter, Natzwiller and its twin camp in neighbouring Schirmeck took the lives of many thousands of prisoners through slave labour in a quarry of pink granite used for Nazi monuments. They died from overwork, ill treatment, malnutrition, exposure in the -30°C winter weather, random killings and ‘medical experiments’, including deliberate burning with mustard gas and injection with lethal diseases.

Among the prisoners were Norwegian Resistance workers, German criminals, communists, French

résistants

and homosexuals, among them 18-year-old Pierre Seel, who had unwisely reported being relieved of his watch during a nocturnal adventure in a Mulhouse park in 1939. The imprudence was to cost him dearly: his name was on a file inherited by the Gestapo after the German invasion. Arrested, tortured and sent to Natzwiller in 1940, he survived and was eventually released because his uniform was distinguished by a blue bar signifying ‘Catholic’, rather than the pink triangle of the homosexual prisoners, mistreated by other prisoners and guards alike. In his book

15

, he reports the death of his lover Jo-Jo, literally savaged to death after several Alsatian dogs were set on him for fun by the guards. A metal pail had been tied onto his head to amplify his screams so that all the assembled prisoners would hear.

16

Natzwiller had witnessed one of the most daring escapes of the war on 4 August 1942 when Czech Major Josef Mautner and four equally desperate detainees, including a French air force officer and a Polish ex-Foreign Legion volunteer, decided to escape before they were starved or beaten to death. Dressing in stolen SS uniforms and driving a car with SS plates ‘liberated’ from the camp garage by a prisoner working there as a mechanic, they succeeded by sheer nerve.

Kapo

Alfons Christmann’s luck ran out when he was caught near the Swiss border a month later. Brought back to Natzwiller, he was tortured in the

Appelplatz

before the assembled prisoners – and slowly hanged on the gallows when the trap twice failed to open. Of the others, Mautner and an Austrian communist named Haas reached Britain via Spain and Portugal; Josef Cichosz survived to join the Free Polish Army; and Alsatian former air force officer Winterberger joined the Free French forces in Tunisia.

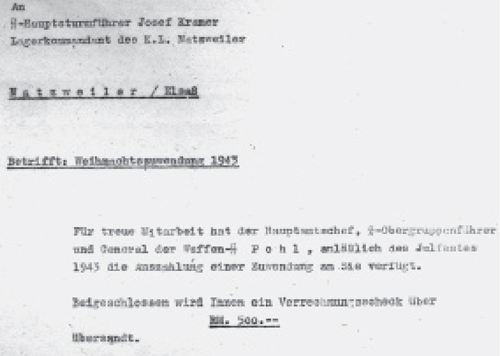

The prisoners from Auschwitz arriving in August 1943 found the Natzwiller camp commanded by Josef Kramer, subsequently promoted to run Bergen-Belsen. Hanged by the British after writing a no-punches-pulled record of his work in the Allgemeine-SS, he recounted his testing of Zyklon-B gas on the first batch from Auschwitz, to ensure the building was airtight. He ordered fifteen female prisoners to undress and go into the chamber. Force was needed to close the door on the screaming women, who had realised that this was not a disinfectant facility as they had been told. One naked woman fought back so desperately that she had to be shot outside. The doors closed, Kramer inserted the precise dose of crystals given to him by Dr Hirt into a special chute and activated them by pouring in water. He switched on the light inside to watch the women die through an armoured glass window, noting that they lost control of their bowels and fell to the floor after ceasing breathing in roughly thirty seconds. For this devotion to duty, he received a Christmas bonus.

Kramer’s bonus award of 8 December 1943. It reads: ‘Re Christmas Bonus. For faithful service, head office chief SS-Obergruppenführer and Waffen-SS General Pohl has authorised payment of a Christmas bonus to you. Please find enclosed a cheque for 500 Reichsmarks.’

In due bureaucratic form, a receipt for the money was requested. By then the other prisoners from Auschwitz had all been killed in small groups, Kramer sending the bodies to Professor Hirt for autopsy, after which the skulls were preserved in Hirt’s ‘racial anatomy’ collection.

17

A number of such spurious anthropological institutions in France were subsidised by German money.

In Bastia prison on the island of Corsica, school teacher Jean Nicoli spent the night of 29/30 August writing letters in his cell. Betrayed by a rival Resistance group, he had been sentenced to death by an Italian military court for running a PCF cell stockpiling arms dropped by Allied aircraft from bases in Algeria. To protect the members of the cell not arrested, he and the other prisoners pretended they had been working for money: a figure of 1,640,000 francs was mentioned during the trial and reported in the press. Told that he was to be shot at 4 a.m., Nicoli’s only concern was to set the record straight after his death, so that his party comrades would know he had taken no money for himself. He was actually not shot but decapitated instead at the Carré des Fusillés of Bastia, four days short of his 45th birthday.

18

Eight days later, the Corsican Resistance rose against the Axis occupation and freed itself with the help of Gaullist forces from North Africa.

On 8 September 1943 the Germans occupied the Italian zone. Two days later Hauptsturmführer Brunner arrived in Nice with a staff of fourteen, to find the Italians completing paperwork necessary to transfer hundreds of Jews by truck across the frontier to safety. The Italian Consulate in the Hotel Continental was raided by SS troops under his command, just after all its files had been removed to Rome. All Brunner could do was arrest the consul and staff, and forcibly deport them. Unaware that thousands of refugees were being spirited across the frontier by French and Italian volunteers, he installed himself in the Hôtel Excelsior by the main railway terminal, anticipating a cull of 2,000 people a day to despatch to Drancy for forwarding on to Auschwitz.

With the Wehrmacht refusing to help, Brunner at first showed more subtlety than in Salonika by publicising forged proof that the transported Sephardim were happily working in Poland and cynically exchanging the French currency of arrested Jews for

zlotys

which they ‘could spend on arrival in the east’. However, even the offer of 10,000 francs head-money to informants saw him unable to assemble more than 2,000 victims in all by mid-month, proving that without the active participation of the French police, the SS and Gestapo would never have amassed so many victims. Finally Brunner used torture to force the first refugees caught to reveal the whereabouts of their relatives and friends.

In September, too, Laval informed General de la Porte du Theil that the poor response to the STO now required him to make up the deficit by handing over all young men in the Chantiers. Refusing to accept this order, the general avoided immediate arrest by stating that he had left instructions for all conscripts to be released, should he fail to return from his visit to Vichy. Shortly afterwards, de Tournemire was forced to go underground to avoid arrest by the Germans, leaving his deputy to find subsidies to keep the movement going. Fobbed off by a succession of top civil servants, he was eventually granted a handout by Laval in the hope of thus gaining control of the Compagnons. Refusing to resign, de Tournemire joined the Alliance network of Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, and activated an undercover spin-off of the Compagnons called ‘Druids’, whose members protected STO runaways by finding false papers for them and helped downed Allied airmen escape France. Its biggest coup was described by Professor R.V. Jones, scientific adviser to SIS, as ‘the most important single piece of intelligence in the war’, after Druids member Jannine Rousseau sent to London detailed information about the V-weapon launch ramps in the Pas-de-Calais.

With society crumbling, parents still had problems with their children. At the end of the summer term, Renée de Monbrison had been asked to remove her daughters from the Collège Cèvenole at Chambord. Having not surprisingly failed their exams because they had been unable to concentrate on lessons, they had fallen foul of the authoritarian headmistress, who made no allowances for the exceptional times. Pastor Trocmé’s daughter was a school-chum of Françoise, but he could not change the teacher’s mind, nor could the popular English teacher Miss Williamson. So Rénée brought the girls back with her to St-Roch and put Françoise’s name down for the

collège

in Moissac, where she immediately made friends with Andrée Giraud, whose family offered her a bedroom. In Chambord 16-year-old Françoise had been considered a child, but Shatta Simon needed every pair of hands and recruited her to guide refugee children from the train station to the Maison de Moissac, cautioning them not to speak loudly in their give-away accents in front of strangers. Twice she was stopped when carrying in her school satchel official stamps of bombed towns and places in North Africa – useful for forging ID cards, as they could not be checked. Afterwards, she despised herself for flirting with the German soldiers to distract their attention.

19