Voices from the Dark Years (59 page)

Read Voices from the Dark Years Online

Authors: Douglas Boyd

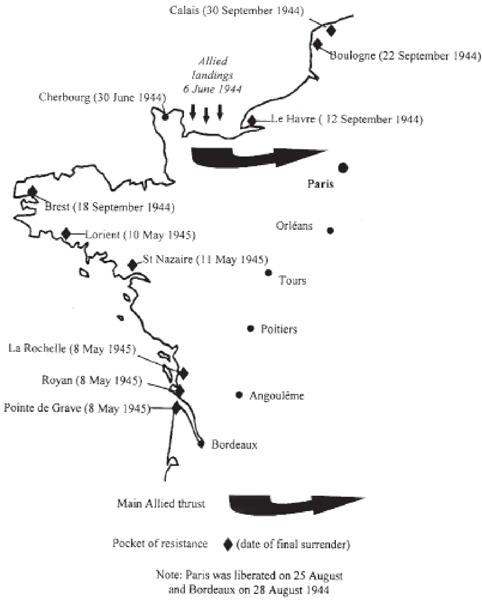

Leclerc’s Free French forces being under Allied command, the liberation of the rest of France was not a tidal wave of freedom washing rapidly across the map, for there was no way that the unassisted FFI could tackle the heavily fortified pockets of resistance around the Atlantic ports. Therefore, when French troops entered Strasbourg on 23 November – the German border had been briefly crossed by US forces early in September – there were many hundreds of thousands of French civilians still living under German occupation in conditions worse than ever, for rations were reduced. German paranoia understandably rose and RAF and US air forces diverted resources to ‘keeping the enemy’s heads down’ and reducing morale to the point where surrender became acceptable to the pocket commanders ordered by Hitler to hold out to the last man and bullet.

Le Havre was not liberated until 12 September, Boulogne on 22 September and Calais on the last day of that month, their civilian populations suffering great privation during this time. At Le Havre, where Allied bombing continued until the day of liberation, each evening after a day’s work in appalling conditions even those few civilians whose homes were still habitable took a bus or train to spend the night in nearby villages less likely to be bombed. Each night 2,000 people carried their remaining belongings or wheeled them on barrows into a partly constructed road tunnel, where they cooked supper over hollowed-out swedes filled with sump oil by the light of carbide lamps and slept on mattresses laid on the damp floor.

On 5 September 1944 the tonnage of high explosive and incendiaries dropped on the town was such that a fire-storm engulfed half the built-up area, melting and igniting road surfaces to produce a column of superheated gases that blew human remains and other large and small debris as far as 30km away. Even those taking refuge in the deep tunnel were not safe, an uncounted number being engulfed by a subterranean river of mud liquefied by the explosions. Survivors were trapped for forty-eight hours without food or water. In the Atlantic port of Brest the entire Sadi-Carnot shelter literally blew up on 9 September, when an unidentified projectile hit a German arms dump in one section of the shelter, killing 350 French civilians in less than a second.

Keenly aware that more of France had been liberated by men in US, Canadian and British uniforms than by General Leclerc, de Gaulle wanted to see the strategically unimportant south-west of France liberated by men in French uniform. The three pockets around La Rochelle, Royan and Pointe de Grave totalled 710 concrete blockhouses surrounded by extensive minefields and barbed-wire entanglements, defended by 30,000 men in German uniform, including anglophobe Sikhs who had changed sides after being captured in North Africa. On 18 September 1944 at Saintes, de Gaulle congratulated Colonel Adeline, provisional commander of FFI forces in the south-west, on the way his men had been containing the Germans in the pockets. ‘However,’ he continued, ‘I want no local armistice of any kind. The German pockets must, and will, be reduced by force of arms.’ The armistices referred to were exchanges of wounded on the front line under flags of truce, for the skirmishes along the coast produced casualties in this forgotten war – forgotten outside France even while it was being fought, the world’s media being focused on the Allied drive into Germany.

Promising that a French armoured division would be sent, de Gaulle could not say when because it required Eisenhower’s consent.

1

After notifying Supreme Allied HQ on 21 September of his intention to liberate the two pockets blocking the port of Bordeaux, de Gaulle ordered General de Lattre de Tassigny on 7 October to relinquish two divisions for this campaign, but Eisenhower made clear who was in charge by not agreeing until the end of November to let them go, effective 25 December – perhaps as an ironic Christmas present.

By then de Gaulle had given General Edgard de Larminat command of the Forces Françaises de l’Ouest (FFO), as of 14 October 1944

2

tasked with the liquidation of the pockets as a matter of national honour. Significantly, de Gaulle baptised the operation

‘

Independance’. There was more to this than personal arrogance: once the US military presence was installed in France, it would take him twenty-two years to eject his transatlantic allies.

Not until 23 October 1944 did the White House and Downing Street recognise de Gaulle’s government ‘subject to the military requirements of the Supreme Commander’.

3

Three days later he decreed that all FFI units not incorporated into the uniformed services or under military command must hand in their weapons or face the consequences – an order that was directly aimed at the communist factions. Since, as head of the provisional government, he had already announced on 15 September that ‘Vichy war criminals’ would be placed on trial, all that remained was to define who was a criminal.

On 7 November de Gaulle used his newly confirmed authority to demand a million German POWs to repair war damage in France and French zones of occupation in Germany and Austria after the end of hostilities. Since Stalin refused to give up any of ‘his’ territory, this meant the UK and US allowing France to occupy some of their territory in occupied Germany. In return for his sometimes wavering support, on 12 November Winston Churchill was given the freedom of the city of Paris.

To invest the landward sides of the three pockets in the southwest, de Larminat had 10,700 men containing the 16,000-man garrison at La Rochelle. Another 5,000 were on the Médoc Peninsula containing the Pointe de Grave pocket. The major pocket of Royan, with its 5,000-plus defenders, was contained by 10,040 FFO men. Their few artillery pieces were captured German or Italian cannon, with limited ammunition supplies. The only advantage they enjoyed was freedom of the air in the form of occasional support from Allied aircraft and the

promise

of aerial bombardment to ‘soften up’ the pockets before an eventual all-out attack.

The German pockets of resistance after June 1944.

It was to plan this that de Larminat conferred at Cognac with US General Ralph Royce commanding 1st Tactical Air Force on 10 December. He claimed afterwards they discussed intensive bombing of the allegedly exclusively military zones of the Royan and Pointe de Grave pockets after the expected reinforcements arrived. Yet, the bombing mission was misleadingly described on the teletype as ‘to destroy town strongly defended by enemy and occupied by German troops only’.

4

The first of the promised armoured troops arrived on 12 December, but Hitler’s Ardennes offensive, opening four days later, and only two days after Montgomery had assured the world that Hitler had no reserves with which to undertake another major initiative, caused Eisenhower to cancel Operation Independance and recall the troops already in the south-west. If he had also cancelled the planned air support for Independance, that would have saved many civilian lives but, in the confusion caused by the unexpected German offensive, Air Chief Marshal ‘Bomber’ Harris received no order to cancel the planned raid.

Photostat of the Royan bombing mission telex.

On Friday 5 January 1945 six Pathfinder Mosquitoes and 217 fully laden Lancasters, plus a Lancaster as airborne command post, took off from aerodromes in Britain, headed for Royan. Between 3.50 a.m. and 4 a.m., the first bombs dropped on the town, and not on the military fortifications outside. A second wave of Lancasters appeared at 5.30 a.m. and dropped their cargoes onto the flaming debris below, causing high casualties among civilians who had emerged from shelters to rescue the first victims. A total of 1,576 tonnes of high explosive and 13 tons of incendiaries destroyed the town centre. Trapped in the burning debris were the bodies of 284 female and 158 male civilians – and thirty-seven Germans.

5

The exact number of French civilian wounded was never agreed. The declared number of dead was also modified, as body parts were recovered during reconstruction up to five years later. The cost of all this destruction with hardly any damage to the 249 blockhouses in the Royan pocket was seven aircraft shot down by German flak crews.

Allied embarrassment resulted in alibis ranging from poor visibility over the target confusing the marker aircraft to an accusation that the French casualties must have been

collabos

and deserved what they got. As to the first alibi, the town was clearly visible by the bomb-aimers during the raid, due to the marker flares and parachute flares. Even more embarrassingly, the navigator’s maps found in shot-down Lancasters had aiming points exclusively in the town area,

6

as indicated by the mission teletype. As to the second, many people remaining in Royan at this late date – after hundreds of civilians had been allowed to leave, to reduce the numbers the German had to feed – were refugees living there under false identities or with no papers at all, and of whom there were no records. It was little consolation that anyone could now obtain papers claiming to have been born in Royan, since all the

état civil

registers had been destroyed.

Historian Peter Krause avers that General Royce’s adjutant in Vittel asked de Larminat in Cognac to give the go-ahead the previous evening, after the ‘target for tonight’ had been decided once meteorological conditions over the Continent were known. The telephone line being out of action, the adjutant’s signal was encoded and sent by radio, received at de Larminat’s HQ at 7.50 p.m. on 4 January. Because staff were at dinner, the signal was not decoded until 12.40 a.m. There was a further delay until 5.30 a.m., when it was translated and finally handed to de Larminat at 8 a.m., by which time Royan was a smoking pile of rubble.

Apart from a truce between 9 and 18 January, during which the Red Cross supervised the evacuation of the wounded and all remaining civilians in the town, the tragedy did nothing to stop the fighting on the ground. The status of FFI men taken prisoner, at first judged terrorists under the Armistice of June 1940 by their captors, was only resolved after de Larminat threatened to shoot ten German prisoners for every FFI fighter executed after capture. At first the Germans refused, but then agreed that all FFI forces taken prisoner would be treated as POWs, on the grounds that the Armistice had been vitiated by their own invasion of the Free Zone in November 1942.

7

On 14 April 1945 – the day after the raid on Dresden – a second huge bomber fleet took off from UK bases: 1,200 B-17 Flying Fortresses headed down the Atlantic coast of France and dropped 7,000 tonnes of bombs, generously distributed throughout the Royan pocket. De Larminat’s men cowering in their shelters on the landward side of the minefields reckoned there were more ‘

amis

’ above the pocket than Germans in it. This was followed up twenty-four hours later by a final US raid, in which three-quarters of a million litres of napalm were dropped in the first use of this new weapon on French soil. Photographs taken afterwards of the town centre of Royan, which had rivalled Biarritz for elegance before the war, resembled those of Ground Zero at Hiroshima – an unbroken wasteland where only a few twisted metal girders poked above the smoking mounds of rubble to show where major buildings had stood.

It is hard to arrive at total casualty figures for the Royan pocket, but in the assault on the Pointe de Grave pocket across the mouth of the Gironde between 14 and 20 April French losses were approximately 400 dead and 1,000 wounded, with 600 dead, eighty missing and 3,230 taken prisoner on the German side. All this was to restore national pride, because the German capitulation was signed just over two weeks later.

8