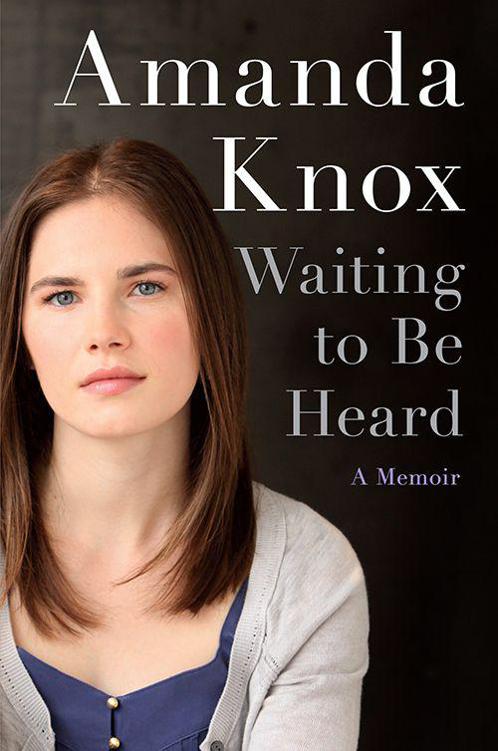

Waiting to Be Heard: A Memoir

Read Waiting to Be Heard: A Memoir Online

Authors: Amanda Knox

Contents

Prologue:

December 4, 2009, Perugia, Italy

Part One:

PERUGIA

Chapter 1

April–August 2007, Seattle, USA

Chapter 2

August 30–September 1, 2007, Italy

Chapter 3

September 2007, Perugia, Italy

Chapter 4

October 2007

Chapter 5

October 25–November 1, 2007

Chapter 6

Morning, November 2, 2007, Day One

Chapter 7

Afternoon, November 2, 2007, Day One

Chapter 8

November 3, 2007, Day Two

Chapter 9

November 4, 2007, Day Three

Chapter 10

November 5, 2007, Day Four

Chapter 11

Morning, November 6, 2007, Day Five

Chapter 12

Evening, November 6, 2007, Day Five

Chapter 13

November 7, 2007

Chapter 14

November 8–9, 2007

Part Two:

CAPANNE I

Chapter 15

November 10–13, 2007

Chapter 16

November 9–14, 2007

Chapter 17

November 15–16, 2007

Chapter 18

November 2007

Chapter 19

November 18–29, 2007

Chapter 20

December 2007

Chapter 21

January–May 2008

Chapter 22

June–September 2008

Chapter 23

September 18–October 28, 2008

Chapter 24

October–December 2008

Chapter 25

January–March 2009

Chapter 26

March–July 2009

Chapter 27

September 1–October 9, 2009

Chapter 28

October 10–December 4, 2009

Chapter 29

December 4, 2009

Part Three:

CAPANNE II

Chapter 30

December 2009–October 2010

Chapter 31

November–December 2010

Chapter 32

December 11, 2010–June 29, 2011

Chapter 33

June 29, 2011

Chapter 34

June 30–October 2, 2011

Chapter 35

October 3, 2011

Epilogue:

October 3–4, 2011

December 4, 2009

Perugia, Italy

I

walked into the ancient Perugian courtroom, where centuries of verdicts had been handed down, praying that a tradition of justice would give me protection now. I glanced at the large crucifix on the wall, crowning the judge’s seat. Blue-capped guards surrounded me, propelling me forward. The room was packed with police officers, lawyers, and journalists, but it was unnervingly quiet. I saw family—my mom, dad, stepmom, stepdad, my sister Deanna—standing over to one side, mouthing, “I love you, I love you.” My other sisters were too young to be allowed in the courtroom, but they were waiting for me just on the other side of the double doors.

The injustice was finally—almost—over.

Four minutes after midnight a bell rang once, and the court secretary announced, “

La corte

.” The judges, wearing black robes, and the jury, draped with the green, white, and red of the Italian flag, came somberly through the chamber door. They looked stubbornly above and beyond our expectant faces as they walked to their places. I was standing between my two Italian lawyers, gripping the hand of the bigger man, the one who had told me again and again over all these months, “Courage, Amanda, we need you to have courage. We will do the rest.”

I took in a deep breath as the judge lifted the paper and began reading the articles on which I was being tried, quietly, monotonously.

Someone behind me wailed, “No!” a second before I heard the judge pronounce, “

Colpevole

”—“Guilty.” Trembling, I slumped into my lawyer, who put his thick arm around me and pushed my face into his chest. Blood was pounding in my ears. I kept moaning, “No, no, no.” I thought,

This is impossible, this is impossible, this is a nightmare, this can’t be true, it’s not fair, it’s not fair.

People were everywhere, shouting for or against me. Hands reached out to me, touched me—I didn’t know whom they belonged to. Over all the noise and confusion, I could hear my sister and mother sobbing.

My legs couldn’t support me. The guards held me up by my armpits and carried me, crumpled, out of the courtroom. In the chaos of my shattered world, I never heard the judge sentence me: “Twenty-six years.”

Done. It was done.

April–August 2007

Seattle, USA

M

om sat next to me in our favorite tall-back booth. Dad slid in across from us. “What’s this about?” he asked.

I couldn’t believe the three of us were actually doing this.

Eating salads with my parents doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it was for me. I’m sure that for them it was hugely uncomfortable. I was nineteen, and as far back as I could remember I’d never seen my parents sit at the same table, much less share a meal. I was a year old and my mom was pregnant with my sister Deanna when she and my dad split up. They had rarely talked to each other since, even on the phone. Proof of how much they both loved me was this reunion at the Eats Market Café in West Seattle. Mom picked at her fingernails. Dad was businesslike. All smiles were for me.

The biggest testament to my parents’ love for Deanna and me was how they’d handled their divorce. They bought houses two blocks apart to give us the benefits of a two-parent family and the gift of never feeling pulled between them. I never once heard either criticize the other. But they were invisible to each other, whether separated by two blocks or two rows at a school play. At soccer games, both cheered on the sidelines buffered by a line of other parents.

The permanent divide meant that when I had news to tell I always had to do it twice. Bringing my parents together this one time was my way of saying: this is the most important decision of my life so far. It was a drumroll to let them know that I was ready to be on my own.

As always, I had gone to my mom first. She’s a free spirit who believes we should go where our passions lead us. When I told her mine were leading me 5,599 miles away from home, to Perugia, Italy, for my junior year of college, her unsurprising response was “Go for it!”

Mom was born in Germany and moved to Seattle as a child, and my grandmother, Oma, often spoke German to Deanna and me when we were growing up. It wasn’t until my freshman year in college that I realized I had a knack for languages and started playing around with the idea of becoming a translator. Or, if only, a writer. When it came time to decide where to spend my junior year, I thought hard about Germany. But ultimately I decided to find a language and a country of my own—one my family hadn’t already claimed. I was sure that would help me become my grown-up self—whoever that was.

Germany would have been the safer choice, but safety didn’t worry me. I was preoccupied by independence. I trusted my sense of responsibility, even if I sometimes made emotional choices instead of logical ones—and sometimes they were wrong.

If I really wanted to become a translator, Spanish or French would have been a more practical choice than Italian. But everyone took Spanish, and I didn’t feel connected to French. My fascination with Italian culture went back to middle school, when I studied Latin and learned about Roman and Italian history. I loved Italy even more when I was fourteen and saw it close up, on a two-week trip with my mom and her family. My Oma, aunts, uncles, stepdad, Deanna, and I piled into two minivans and drove through Germany and Austria to visit relatives and celebrate Oktoberfest in Munich before heading south into Italy, to see Pisa, Rome, Naples, Pompeii, and the Amalfi Coast. The history I’d studied became real when we visited the Coliseum and the ruins of Pompeii. I remember pointing out things to my family and babbling about factoids I’d stored away, so much so that they nicknamed me “the tour guide.” I was charmed by the narrow, cobblestone streets and the buildings rooted into the earth that were so different from what I was used to in Seattle. It was a month and a half after 9/11, and all the Italians we met were warm and sympathetic. I came away thinking Italy was a welcoming, culturally and historically rich country.

As a sophomore in college, I signed up for Italian 101. Then, when I found out that the University of Washington hosted a summer creative writing program in Rome, taught in Italian, it felt like kismet. It combined everything I was looking for. Step one was to master Italian and immerse myself in the culture for nine months in tiny Perugia. Then I’d be ready to take on Rome in June.

Now I had to convince my dad. He’s a linear thinker who works in finance. He’s into numbers and planning. As practical and organized as he is, he’d have a lot of questions. So I approached him armed preemptively with the answers.

I also had another mission when I’d set up the two-parent lunch. I wanted to show my dad that I loved him and my mom equally. While I was asking him to trust me in Perugia, I was also asking to be forgiven.

During my first two years in college, I’d gotten better at seeing things from other people’s perspectives. I started mentally cataloguing the times I’d been selfish. A big one was how I’d treated Dad when I was a teenager.

Growing up, I officially spent every other weekend with him. Dad wasn’t a micro-parent; he left all the day-to-day details to my mom. When I had a decision to make I turned to her. She would lay out the options and encourage me to make the choice myself. Dad wasn’t part of the process.

The house he shared with his second wife, Cassandra, was theirs, not mine. When my half sisters, Ashley and Delaney, were born, Deanna and I were relocated from our shared bedroom in that house to pullout couches in the playroom. My real home was the one with my room, my sister, my mom, and her second husband, Chris. That’s where I felt most myself. Mom let us wear whatever we wanted and build forts in the backyard. On rainy days, it was Deanna’s and my job to redirect the lost slugs that pilgrimaged into the dining room beneath the backdoor. Dad required us to use drink coasters, arrange the movie cassettes and CDs in alphabetical order, and wear matching outfits.

At fourteen, I told Dad I was too busy with my extracurricular activities and friends to stay over with him anymore. The truth was that I was uncomfortable with the awkward divide between my life and his, so I widened the gap between us. Now I wanted to close it.

As I began researching programs in Italy, I realized that having my dad’s support was fundamentally important to me. I’d never rehearsed any part in a play as hard as I had this conversation in my head. I wanted my dad to be impressed. I wasn’t at all sure what I would do if he said no. Once we were seated, I couldn’t wait a second longer. I started making my case even before the waiter brought us menus.

“Dad,” I said, trying to sound businesslike, “I’d like to spend next year learning Italian in a city called Perugia. It’s about halfway between Florence and Rome, but better than either because I won’t be part of a herd of American students. It’s a quiet town, and I’ll be with serious scholars. I’ll be submerged in the culture. And all my credits will transfer to UW.”

To my relief, his face read receptive.

Encouraged, I exhaled and said, “The University for Foreigners is a small school that focuses only on language. The program is intense, and I’ll have to work hard. The hours I’m not in class I’m sure I’ll be in the library. Just having to speak Italian every day will make a huge difference.”

He nodded. Mom was beaming at my success so far.

I kept going. “I’ve been living away from home for almost two years, I’ve been working, and I’ve gotten good grades. I promise I can take care of myself.”

“I worry that you’re too trusting for your own good, Amanda,” he said. “What if something happens? I can’t just make a phone call or come over. You’ll be on your own. It’s a long way from home.”

Dad has a playful side to him, but when he’s in parent mode he can sound as proper as a 1950s sitcom dad.

“That’s the whole point, Dad. I’ll be twenty soon, and I’m an adult. I know how to handle myself.”

“But it’s still our job to take care of you,” he said. “What if you get sick?”

“There’s a hospital there, and Aunt Dolly’s in Hamburg. It’s pretty close.”

“How much is tuition? Have you thought about the extra costs involved?”

“I’ve done all the math. I can pay for my own food and the extra expenses,” I said. “Remember I worked three jobs this past winter? I put almost all of it in the bank. I’ve got seventy-eight hundred dollars saved up.”

Dad wove his fingers together and set them, like an empty basket, on the table. “How would you get around?”

“The university is right downtown, and there’s a city bus,” I said. “And Perugia is small. It’s only about a hundred and sixty thousand people. I’m sure I’ll learn my way around really fast.”

“How will you stay in touch with us?”

“I’ll buy an Italian cell phone, and I’ll be on e-mail the whole time. We can even Skype.”

“Will you live in a dorm?”

“No, I’ll have to find my own housing, but I’m sure I can get a good apartment close to campus. I checked with the UW foreign exchange office—they say the University for Foreigners will give me a housing list when I get there. I’d really like to live with Italians so I can practice speaking the language.”

I didn’t know what my father would think, but I was pretty sure we’d be going back and forth for weeks no matter what. To my astonishment, he said yes before I’d picked up my fork.

“I’m proud of you, Amanda,” he said. “You’ve worked hard and saved a lot of money. I can tell how much this means to you.”

I knew I’d be just one of about 250,000 American college kids heading abroad in the fall, but this was the most momentous step I’d taken in my life so far. And I was unusual among the people I knew—most of my UW friends weren’t studying abroad. I felt exceptional. I felt courageous. I was meeting maturity head-on. I’d come back from Italy having evolved into an adult just by having been there. And I’d be fluent in Italian.

T

his year overseas would be the first time I’d ever really been on my own. During senior year at my Jesuit high school, Seattle Prep, almost all my friends sent applications to schools hundreds of miles from home. Some even wanted to switch coasts. But I knew that I wasn’t mature enough yet to go far away, even though I didn’t want to miss out on an adventure. I made a deal with myself. I’d go to the University of Washington in Seattle, a bike ride from my parents’ houses, and give myself a chance to season up. By the time high school graduation came around, I’d already started looking into junior-year-abroad programs.

Most of my high school class had been more sophisticated than I was. They lived in Bellevue, a decidedly upscale suburb with mansions on the water. Their neighbors were executives from Boeing, Starbucks, and Microsoft.

I received financial aid to attend Prep and lived in modest West Seattle, not far from my lifelong friend Brett. I was the quirky kid who hung out with the sulky manga-readers, the ostracized gay kids, and the theater geeks. I took Japanese and sang, loudly, in the halls while walking from one class to another.

Since I didn’t really fit in, I acted like myself, which pretty much made sure I never did.

In truth I wouldn’t have upgraded my lifestyle even if I could have. I’ve always been a saver, not a spender. I’m drawn to thrift stores instead of designer boutiques. I’d rather get around on my bike than in a BMW. But to my lasting embarrassment, in my junior year, I traded my friends for a less eccentric crowd.

I’d always been able to get along well with almost anyone. High school was the first time that people made fun of me or, worse, ignored me.

I made friends with a more mainstream group of girls and guys, attracted to them by their cohesiveness. They traveled in packs in the halls, ate lunch together, hung out after school, and seemed to have known each other forever. But in pulling away from my original friends, who liked me despite my being different, or maybe because I was, I hurt them. And while my new friends were fun-loving, I was motivated to be with them by insecurity. I’m ashamed for not having had the guts to be myself no matter what anyone thought.

This didn’t change who I was. Like most teenagers, I was too well aware of my flaws. I felt lumpy in my own skin. I was clumsy with words, and I knew I was way too blunt. I’d do things that would embarrass most teenagers and adults—walking down the street like an Egyptian or an elephant—but that kids found fall-over hilarious. I made myself the butt of jokes to lighten the mood. The people who loved me considered my kookiness endearing. My family and friends would shake their heads good-naturedly and sigh, “That’s Amanda.”

Soccer is where the boundaries fell away. I was good at it, and that always allowed me to feel on par with others.

In college I finally found my footing off the field. I stayed in touch with Brett and met a small group of intelligent and offbeat students at the university’s climbing wall and in my dorm. I dated a Mohawked, kilt-wearing, outdoorsy student named DJ. My next-door neighbor was a girl from Colorado named Madison. She and I grew close and looked up to each other. She wasn’t like most of the students. She didn’t play sports, drink, smoke, or go to parties. She was a conflicted Mormon and a musician, majoring in women’s studies and photography. I kept her company at night in the campus dark room. She encouraged me to be myself.

Most of my other friends were male. We played football, jammed on the guitar, talked about life. After we smoked pot we would choose a food category—burgers, pizza, gyros, whatever—and wander around the neighborhood until we found what we considered the best in its class.

As I got ready to leave for Perugia, I knew I hadn’t become my own person yet, and I didn’t quite know how to get myself there. I was well-meaning and thoughtful, but I put a ton of pressure on myself to do what I thought was right, and I felt that I always fell short. That’s why the challenge of being on my own meant so much to me. I wanted to come back from Italy to my senior year at UW stronger and surer of myself—a better sister, daughter, friend.

While I was figuring out what I would need in Italy—my climbing gear, hiking boots, and a teapot were among the essentials—old friends from high school and new friends from college dropped by with well-wishes, little presents, and gag gifts.

I received a blank journal and a fanny pack and tins of tea. Funny, irreverent Brett brought me a small, pink, bunny-shaped vibrator. I was incredulous; I had never used one.