Walking with Abel (17 page)

Authors: Anna Badkhen

“Milk and yogurt and butter—if you have it every day you’ll never get sick! Rice constipates you. That’s why I’m not getting better, because of the rice. If you look at a boy who drinks milk and a boy who eats rice, you’ll see the difference. The boy who drinks milk is much healthier.”

One of Isiaka’s teenage daughters rolled her eyes. She’d had enough of his rants. She’d had enough of the bush.

“Tell me,” she asked Pygmée, “is there a good job for me in Djenné?”

“Your job is to stay here and feed the old man tasty rice,” Pygmée said.

But Isiaka fluttered his skinny arms. “I don’t care for her rice! I don’t like rice! I just want milk! But there isn’t enough! Because this is not milk season.”

It was al Butayn, the Little Belly, Delta Arietis. An evolved giant star in the constellation of Aries, one hundred and seventy light-years from Earth, twice our sun’s mass, ten times its radius, forty-five times more luminous. It proclaimed the beginning of the hot season, the hardest time of the year. The hot season, the Fulani said, lasted two months. That year, it would last three.

“The beginning of the waiting for rain,” Moussa Bâ the oracle had explained to me in Kouakourou. The sun shone hotter, brighter, longer, and at night mosquitoes filled the ears with their thin song. The swales around the Diakayaté camp held shallow membranes of tepid water or no water at all. Day temperatures hovered around a hundred and twenty degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, but where was the shade? Even the clouds that now gathered in corners of the sky each day seemed to cast none. The Diakayatés spent more and more time in the heated crepuscule of their huts, coughing at the dust that sieved from the thatch. Acacia trees had begun to shed their feathery pinnations. Each time glossy starlings lifted off their spiny perches the leaves would petal down into Fanta’s cooking, upon the cattle that grew thinner behind the calf rope, upon the straw mat where I was nursing my malady.

Last year’s harvest was almost gone, and in markets and villages grain was expensive. From the country’s north and south trickled stories of families broken, displaced by war and hunger, starving in refugee camps and in overcrowded homes of relatives. When they heard such stories the nomads would change the subject. Hunger was merely a state of living. When you didn’t have enough to feed your children you farmed them out to someone who did. Pygmée, for example, was raising his own four children and two nephews and a niece whose parents could not afford to provide for them. Besides, it was just a matter of months before there would be enough milk again.

The Sahelian moonscape was hammered out of cycles—nanorhythms of breath drawn and released, circadian processions of darkness and light, weeks of killer heat and absolutions of rain, droughts and famines alternating with years of plenty. The Earth turned, inexorable, impassive. Agama lizards went on clicking and ribboning the world into Möbius strips of their courtship circuits millions of springs old, and the first mangoes ripened in the groves south of the bourgou.

“Anna Bâ!” said Oumarou. “In your France in America is it also very hot and dry?”

It had been snowing when I had boarded the plane in New York. But Fulfulde had no word for snow.

“Galaas,”

I said: ice, a loanword from the French. I said that in the place where I was born there were entire months that were so cold that ice fell from the sky instead of rain, every day, and stayed on the ground for weeks at a time, sometimes knee-deep.

For once I had told a story the Diakayatés’ anthology of the world could not accommodate. Everybody laughed. Impossible! Then I worked it out: my hosts were picturing the only ice they knew, the scarlet and orange frozen slushies of hibiscus and ginger and baobab juice they sometimes bought in the Monday market in Djenné. Paisley fields of sweet and sticky fuchsia and daffodil and pale yellow. Savannah glacé. And I laughed with them.

A

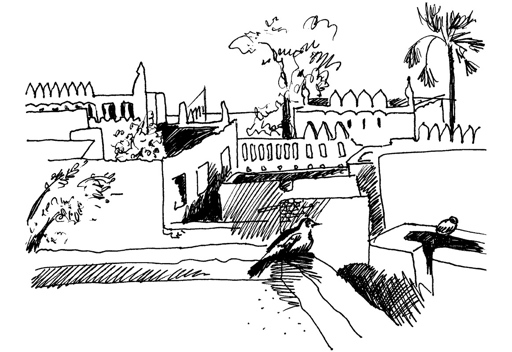

vermilion sunrise on a Monday. A wide sky unspooled in puffy lace of cirri, and in the foreground a small yellow weaver lifted off a thorn tree branch and the branch sprang back up, bounced, halted. In Djenné at dawn all woke and began instantly to move, mate, go, do in an uproar of movement and sound: donkeys brayed, rock pigeons with their redrimmed eyes mounted one other, roosters clucked and crowed, women called out to neighbors over banco walls, talib boys begged door-to-door, motorcycles revved and belched black ash, pancake vendors lit fires under honeycomb griddles, children ran up alleys to borrow and deliver fire, matches, salt. In the bush, every sound, every thing, stood out in precious starkness because for everything there was space enough. When a flock of turtledoves rose from the fallow millet fields on blue wing, each individual wingstrike sounded.

The litany of morning greetings. A silent Lipton ceremony with last night’s milk. Distant rattle of early market-bound carts. Smears of red dust on the horizon where cattle slogged back from nightherd. Fanta was preparing to visit her younger sister, whose daughter had died of malaria the day before. Sad news traveled fast in the bush. The girl had been fifteen, the same age as Hairatou. Three days earlier Fanta had walked all day to pay condolences to a niece who had just lost a two-year-old son. He had been coughing and he had been very hot to the touch, and then he died.

His death, too, pealed through the bush.

“May God protect us all,” said Fanta, because that was what you said at times of death.

“Sometimes children die,” said Oumarou, who knew.

Children in Mali died more often than those in any other part of the world. At night Djenné’s chief pediatrician rode his motorcycle to a riverside bar, where there were Ivorian hookers and Malian beer and groves of eucalyptus to block out the heartbreak and helplessness of his days. Healthcare experts cited malnutrition and communicable disease as the two main causes of child mortality. The Fulani also named two causes. One was disease. The other was the witchery of an owl. Fanta said it was an owl that had killed her grandnephew.

T

he owl lives at the cemetery. At night it leaves its roost and picks up clawfuls of dust from the graves. If you are an adult and you sleep outdoors during the months when it is cool enough for people to pray inside the Djenné mosque, the owl will sprinkle you with cemetery dust and you will become very sick.

The owl flies over villages and nomad camps, listening, listening. If it hears a child cry in the night, it gives that child malaria or pneumonia. Such children almost always die and then the owl takes their souls.

An illness inflicted by an owl is “perceived to be untreatable, particularly with modern medicines,” wrote the anthropologist Sarah E. Castle, who studied child mortality among the Fulani in Mali. But no one can tell whether a sick child has fallen prey to an owl until that child dies. Only then does owl sorcery reveal itself, to old men and women and to traditional healers who know such things.

If you eat owl meat, you and your children will be protected from killer owls for the rest of your life. The hitch: such owl protection is more effective if passed down by the mother, not by the father, and women rarely can afford to eat owl meat because the hunters who sell owls at the fetish market charge a lot for it, though slightly less than for a pied crow.

Once in spring I watched the Diakayaté children stone a Pel’s fishing owlet. It was only slightly larger than my hand. Led by young Amadou the children took turns throwing at it lumps of shit, dirt, straw. The bird panted. Yellow riverine eyes blinked asymmetrically. It fluffed its flightless wings, then hopped away, rotating its head all the while toward its molesters, stunned by their cruelty. It dragged a crippled rufous left wing away from the camp, toward the green grass of the withering fen. Adults and teenagers watched from the shade of a thorn tree. At last Amadou daringly stepped forward, grabbed it by the wings, carried it a few steps, slammed it against the goopy ground. Soon it was dead.

A

fter Fanta left on her condolence call I hiked to Djenné. Monsieur Koulibaly was waiting for me at Sory Ibrahim Thiocary School. On Mondays all Djenné schools were closed, to give the students an opportunity to earn some coins in the weekly market, and we could hold our lesson undisturbed. We sat beside a plywood desk in a deserted classroom, out of the sun, and practiced simple dialogue.

“Are you healthy?”

“

Al ham du lillah

, I am healthy.”

“Your daughter was sick yesterday. Is she healthy?”

“She is very healthy now,

al ham du lillah

. . . Excuse me, Monsieur Koulibaly, how do you say in Fulfulde ‘She is not very healthy’?”

“You don’t. If you say ‘She is not very healthy’ or ‘She is still sick,’ it means ‘She is on her deathbed, she is dying, she will not recover.’ Even if that’s the truth you cannot not say it. It means you have given up hope.”

Giving up hope was an infraction against the omnipotence of God.

I looked out the glassless window into the vast school courtyard. Empty. I thought of the schoolchildren who were very healthy now,

al ham du lillah

, and then they were gone. I thought of the children I had seen that afternoon in the market on my way to the school. A preteen boy who tripped and fell in the dirt road choked with motorcycles and draught horses and donkey carts and bicycles and pushcarts, and lay there eerily motionless until a tall young woman passing by in silver heels and a glittering and richly embroidered long dress bent down and grabbed him by the forearm and yanked him up and steadied him somewhat vertically and kept going, leaving the boy to fumble in the dust with his feet for his blue rubber flipflops.

“Fulfulde,” Oumarou told me once, “is the hardest language, because it has so many nuances and meanings.”

—

In the afternoon I joined the Diakayaté men on the mound of unclaimed skeletons at Djenné’s north gate and we hired five spots in a horsecart back to camp. The two Sitas sat up front, next to the driver, legs dangling off the cart, talking incessantly. I sat on my backpack behind the driver, my back against a sideboard. Across from me a teenage Bozo girl with Down syndrome clutched a pink plastic doll with fuchsia hair. The girl’s face and neck were very dirty and her teeth were very white and straight. Our toes touched. To my right a young woman in a fish-print dress, the teenager’s mother or sister, gripped with her thighs a naked toddler girl who wore strings of blue and white beads around her neck, wrists, and waist. Gris-gris against the evil eye, genii, sickness, poverty, life. In the back of the cart an older woman, probably the toddler’s grandmother. Next to her, perched on a sideboard, Boucary and Ousman. Ousman held by a leash a gray nanny goat. From time to time the teenage girl sank her fingers painfully into the goat’s side and twisted. Ousman pretended not to notice. The horsecart jolted and shook. Sita Dangéré’s bony left buttock drilled into my left foot, the driver’s leather whip stroked my arm and neck on each backlash, and the hot metalwork on the cart’s sideboard sawed into my back. The naked toddler sang a wordless ballad of bumpy roads. In the sweet yellow haze of sunset, cattle in the swales moved like water. Somewhere Fanta was walking back to camp from her mourning duty in torn flipflops until at last she took them off and balanced them on her head and walked the rest of the way on the treebark soles of her bare feet.