Walking with Abel (5 page)

Authors: Anna Badkhen

One belonged to Oumarou’s firstborn, Djamba, who already had been married when she died many years ago at the age of seventeen. The other belonged to Oumarou’s eleven-year-old son Amadou. They were his children from his first wife, Hajja, who died on transhumance during the great famine thirty years earlier and was buried far away, north of the Niger River. The acacia branches Oumarou had felled upon the graves of Djamba and Amadou to keep away wild animals were long gone. Maybe the wind had dragged them away. Maybe women had collected them for kindling. Maybe the termites had eaten them into frass that simply had disintegrated with time.

“You only have one child?” Oumarou’s niece Salimata clicked her tongue, turned toward me her head of long grayhaired cornrows, squinched her aquiline nose. The golden hoop she had threaded through her septum jiggled. She walked briskly; ten kilos of water on her head were crushing her sixty-year-old bones. “Oh, oh, oh. You must have a lot. At least five.”

“How many do you have?”

“Seven are still alive.”

“And the others?”

“There were three more. God took them. We move. They died on the move.”

The Diakayatés did not discuss the graves much. The Fulani code of honor was strict and punitive: a woman who cried over her dead child weighed him down, barred his soul from entering the heavenly gates, and barred the child, too, from testifying in heaven on her behalf. The Fulani submitted to the awesome and unlearnable omnipotence of God. They celebrated impermanence the way the Japanese watched cherry blossoms in spring. The way the Tibetans poured the entire vibrant universe of a mandala into a river. Sufi teachers promised that freedom lay in the absence of choice, but the nomads’ practice may have predated their conversion to Islam. Stoicism was the discipline of suffering, and transhumance demanded both. In the second century

BC

the Greek historian Agatharchides wrote of a pastoral sub-Saharan people he called the Troglodytes who lived on milk and blood of cattle and buried their dead to the accompaniment of laughter. The Roma, Europe’s last remaining nomads, dance in mourning.

—

By the beginning of the second millennia, around the time Islam’s early forays into the bourgou delivered spindle whorls, rectilinear houses, and brass, people had abandoned the settlement of Djenné-Djenno. A hundred acres of culture painstakingly carved out of the hardscrabble geography since the third century

BC

had simply withered, become effaced. Why? The oral epics are mum. From midsummer to late winter, when the wadis around the prehistoric grounds run with water, laundresses spread their bright pagnes over the relics to dry.

A different story survives. A thousand years ago, around the time of Djenné-Djenno’s mysterious decline, nomadic Bozo fishers began to settle into permanent banco villages along the Bani, the Niger’s tributary. On a large island hammocked in the vascular tangle of the river’s braided stream the Bozo sacrificed the young maiden Tapama Djennepó, alias Pama Kayantau, asking the genii of the floodplains to bless a new settlement they called Djenné. They immured the girl alive.

The city grew to eminence. It became a medieval stopping point on the trans-Saharan caravan route for traders of gold, salt, and slaves. A “blessed town,” the seventeenth-century Timbuktu scholar Abd al Rahman al Sa’adi called Djenné in

Ta’r-ıkh al Sudan

, the earliest surviving written history of the Songhai Empire, which in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries stretched more than two thousand miles from the Atlantic Ocean to the heart of modern-day Niger. Camels and pack donkeys clacked by Tapama’s tomb. Islamic scholars flocked past it to madrassas. Sekou Amadou’s purist jihadis let it be. A thousand years after the sacrifice, in 1988, the United Nations designated Djenné a World Heritage Site—like the Mayan city of Chichén Itzá, like the Taj Mahal—and town fathers erected next to the tomb a signboard that read

TOMBE DE LA JEUNNE FILLE TAPAMA GENEPO SACRIFEE POUR PROTEGER LA VILLE CONTRE LES MAUVILLES ESPRITS

. In the twenty-first century the tomb’s clay hexahedron still slanted toward the river on the southern edge of the town, next to a fetid black rivulet of refuse. Slanted toward the necropolis of the Sahel, where a child’s grave always watched over the living.

—

Oumarou had three other dead children. They were buried at two different resting stops on his migration route. Each campsite was a gravesite. Each season the old cowboy measured with his footsteps the distance from one dead child to the next.

Two thousand footsteps per mile. Twenty to forty thousand footsteps a day. Seven to fifteen million footsteps a year on the raw hide of the Earth: the drawn-out journeys of biannual migration, and in between, the constant movement of twice-daily pasturage, of daily roundtrips to waterholes and distant markets. Every footfall contains the kernel of our becoming, the meganarrative of our timeless hejiras, our common travelogue writ large. Every footfall brings the walker closer to the next patch of shade, the next well, the next resting spot. Every footfall is a leap of faith that at the end of the trek lie pasture and water for the cows, redemption, forgiveness, self-compassion.

Every footfall begets a separation. Each time the Diakayatés moved camp they left behind huts sedulously wainscoted and torn down, loved ones, lovers, graves.

Salimata pitied me. She knew the heartbeat of the savannah with the soles of her feet and she knew that the land preserved all the memories past and future and replayed them again and again in cycles that lasted a season, a decade, an eternity. Cycles of plentitude and uncertainty, of holding on and letting go, of life and death and life again.

“Is there a land without death, Anna Bâ?” she said. “We are used to leaving everything.”

To spend a lifetime walking away. To bid farewell over and over, all the time. To anchor your heart to the next campsite and then move on. To have your heart broken and reset like a bone.

For a while my beloved had lived in the desert. When the land stilled in the late-afternoon heat and ocotillos cast shadows blue and long like sundial gnomons we would watch stormcells collide sixty miles away. But he was not free to give me his love and did not give it freely. He was a landscape of desire, and I was always trespassing, and every goodbye was our last. Each time we met it was to walk away.

Don’t you know, Mama? Carrying water has nothing on grief.

A

bove the graves in the eucalyptus trees there lived a murder of pied crows. Whenever the Diakayaté women passed by the grove the birds would fling themselves out of the fragrant grove at the women’s repartee and caw their own carnivorous tattles.

A pied crow is the best medicine for epilepsy. You pluck it, cook it in a pot, and eat it whole. But it is hard to find a pied crow even in Djenné’s fetish market on a Monday because a crow is very difficult to kill. The hunters who do sell it charge a lot of money for it.

If you catch a pied crow alive, which is all but impossible because it is such a cunning and evasive bird, and pull down its eyelids, you will find a sentence from the Koran written in Arabic on the sclera of its eyes. If you read that sentence, spit into your palm, and wish for anything—a lot of cows, or money—your wish will come true. But pied crows are even harder to catch alive than to kill.

A pied crow does not lay eggs, not ever. It steals the eggs of other birds, takes them to its nest, and whispers an incantation over them, turning the fetus birds inside into pied crows.

Perhaps sorcery is the kind of covenant one needs to level with this land, to live and walk in the bush of ghosts.

S

unup in the Sahel. Thousands of cattle egrets hung on the blue wind, laced the air with dawn-coppered wingbeat. A bright scarlet sun pushed away the night and in the west there appeared a gauze of dust. A hint of cattle. Hairatou, Oumarou’s youngest daughter, quit poking the manure fire she had lit with the coals she’d borrowed from an uncle’s camp and rose to see. The animals no larger than gilded peppercorns on the miraging horizon between Dakabalal and Doundéré, the cattle driver himself invisible.

“That’s Ousman with the cattle, Papa.”

“Where—oh yes. So it is.”

“I knew it!”

The Bedouin who in the nineteen forties accompanied the British traveler Wilfred Thesiger through the Empty Quarter of Arabia knew camels that way. The dark oval beauty tattoo around Hairatou’s lips grew broader with her proud smile.

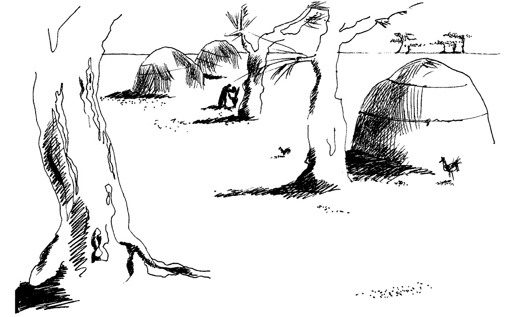

Hairatou was fifteen. A day earlier, with a forefinger dipped in Ultra Blue No. 1 Tulip clothes dye, she had painted on the pale clay wainscot of her parents’ hut images of cattle and cowherds, stick figures with crosses for the broadbrimmed hats of men and ovals for the cows’ humps. She had painted larger standalone crosses for birds aflight and gargantuan spoons that looked like Venus symbols. Were the hut to remain standing, some future scientists would wonder about those, and about the large and hairy vulvae that were Hairatou’s renderings of the calabash lids she wove in her spare time out of grass and colored thread.

Hers was not the elegant artwork of Tassili n’Ajjer, painted with mineral pigment that silica had bound to rock. Nor had she ever heard of ancient pictographs, those or any others. Her own art would in fact disappear at the onset of the rainy season, when her parents dismantled the hut. The cuticle of her finger would remain bluestained for days.

“Ousman’s coming, Mother!”

Ousman was Oumarou’s second-eldest living son. The eldest was Boucary, a gaunt and withdrawn man who lived separately from his father and herded almost exclusively goats and sheep because he was a lousy cowboy and could not be trusted with cattle. Ousman was thirty years old and had a wife and two small sons and because of that raised his own hut, which, wherever the family camped, he built three dozen yards south of his father’s. Like Oumarou he was reed-thin and tall. Under his various faded blue boubous he always wore a Los Angeles Lakers singlet of yellow rayon. On his feet, the narrow plastic lace-ups made in Côte d’Ivoire that all nomads wore irrespective of gender and that market vendors who sold them for two dollars a pair called Fulani shoes. They came in combinations of blue, white, and green, and their dense soles stopped thorns, mostly. Ousman’s eyes were strange. Milky faraway eyes. Not cataractic but as though patinated with silver. They made me stare immodestly.

Ousman had been herding his father’s cows since midnight and now was whooping them back to camp at a trot on a red clay path that folded out of the end of the Earth, past indigo hollows that still cradled last night’s cold against the long light of early morning.

The cows slowed to a walk as they approached, and at the western edge of Oumarou’s campsite they jostled and stepped in place, lowing in earnest satiation just to the west of a shaggy yellow and frayed rope strung from a thorn tree to a short stake in the ground a few paces away. The first thing a Fulani family did whenever it arrived at a new campsite was to drive into the ground the stake to which the calf rope was tied, to claim an outpost and to divide the new landscape into the domestic and the animal, the female and the male. Only after Oumarou or Ousman or Oumarou’s youngest son, Hassan, had tied the calf rope would the Diakayaté women hang their pagne bundles and calabashes from an acacia, steady their kneehigh mortars in its shade, drag three rocks together to build a new fire site, sweep the ground clean of thorns. The cows knew to stand to the animal side of the rope. Only rarely a wayward yearling, not yet educated in the way of the world, would venture hearthside to pick at leftovers in cooking pots or steal some roofing grass from a hut.