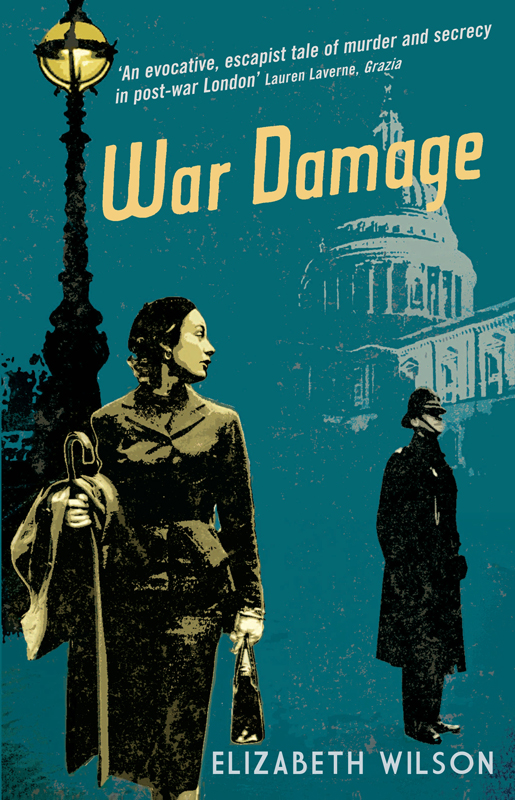

War Damage

Authors: Elizabeth Wilson

Â

ELIZABETH WILSON

is a researcher and writer best known for her books on feminism and popular culture. She is currently Visiting Professor at the London College of Fashion. Her novel

The Twilight Hour

is also published by Serpent's Tail.

Praise for

War Damage

âThe era of austerity after the Second World War makes an entertaining and convincing backdrop to Elizabeth Wilson's fine second novel ⦠A delight to read' Marcel Berlins,

The Times

âCultural historian Elizabeth Wilson used post-Second World War austerity Britain as the setting for a crime novel in her atmospheric

The Twilight Hour

(2006), set around bohemian Fitzrovia and Brighton in 1947. In this loose sequel, she again brilliantly evokes that bleak world of bomb sites and food shortages ⦠Wilson presents a nation struggling to get back on its feet, but she does not overdo the period detail ⦠Regine is an idiosyncratic, vivid protagonist' Peter Guttridge,

Observer

âA first class whodunit ⦠The portrait of Austerity Britain is masterfully done ⦠the most fascinating character in this impressive work is the exhausted capital itself' Julia Handford,

Sunday Telegraph

âWilson evokes louche, bohemian NW3 with skill and relish' John O'Connell,

Guardian

âThis book is as stylish as one would hope. An evocative, escapist tale of murder and secrecy in post-war London,

War Damage

paints a picture of a city that, way before the '60s (even in the rubble of the Blitz), was swinging' Lauren Laverne,

Grazia

âA sleek and vivid period piece'

Gay Times

Praise for

The Twilight Hour

âThis is an atmospheric book in which foggy, half-ruined London is as much a character as the artists and good-time girls who wander through its pages. It would be selfish to hope for more thrillers from Wilson, who has other intellectual fish to fry, but

The Twilight Hour

is so good that such selfishness is inevitable'

Time Out

âA vivid portrait of bohemian life in Fitzrovia during the austerity of 1947 and the coldest winter of the twentieth century'

Literary Review

âA book to read during the heatwave to keep you cool. The observant writing ensures that the iciness of the winter of 1947 rises off the page to nip your fingers ⦠[An] exciting, quirky story and a gripping evocation of an icy time'

Independent

âFantastically atmospheric ⦠The cinematic quality of the novel, written as if it were a black and white film with the sort of breathy dialogue that reminds you of

Brief Encounter

, is its trump card'

Sunday Express

âAn elegantly nostalgic, noir thriller; brilliantly conjures up the rackety confusion of Cold War London'

Daily Mail

War Damage

Elizabeth Wilson

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library on request

The right of Elizabeth Wilson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright © 2009 Elizabeth Wilson

The characters and events in this book are fictitious.

Any similarity to real persons, dead or alive, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 2009 by Serpent's Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.serpentstail.com

eISBN 978 1 84765 508 0

Have you ever heard of Fei Tsui jade? ⦠It's the only really valuable kind.

Raymond Chandler,

Farewell, My Lovely

one

âH

OW DID YOU GET A KEY?

'

Charles slid his smile sideways, but didn't answer as he unlocked the art annexe door. The neglected appearance of this outbuilding reflected the status of art at the school. Easels and shelves for paint and brushes left little floor space for pupils, since the studio also functioned as an office, and was furnished with a couple of old wooden filing cabinets, a desk, two bentwood chairs, and a sagging antique chaise longue. A door at the back opened onto a darkroom the size of a cupboard, separated from the main room by a flimsy partition.

Charles locked the door again on the inside, leaned back against it and stared at Trevelyan â Harry â whose eyes widened with fear and adoration. Charles knew it would be all right then. âGod!' He took hold of the boy's shoulders, steered him towards the convenient sofa, pushed him down on to it and was about to undo his flies. But then he paused and took Trevelyan's face â so gently â between his hands and kissed him. Charles's heart was beating frantically. He'd thought about this all summer. And the boy wanted him too. He was stiff. Charles was shaking as he undid the heavy flannel and his throbbing prick wrung a groan from his throat. Trevelyan came almost at once with a little strangled whimper.

Charles left a stain on the sofa. He didn't care. He lay back, breathing heavily. But as time passed a fearful lethargy came over him. He smiled at the boy and stroked his hair. But the obsession that had sustained him since the end of last term had leaked away with his sperm and he was left with a feeling of utter emptiness.

Trevelyan was trying to tidy himself up. âHadn't we better go? What if Carnforth comes in?'

Charles laughed. âHe won't, will he? Everyone's gone home. That's why I told you to bring your stuff â we don't have to go back to main school.' For the annexe, located at the far end of the playing fields, was near the goods entrance so that it was easy to come and go without being seen. Anyway, no one came down here after school; except, of course, the art master himself. And if Carnforth

had

by an unlucky chance turned up, well â¦

âBut â¦' Trevelyan dimly sensed that there was more to it than that.

âActually,' drawled Charles, âCarnforth lent me the key. I told him I wanted to finish my backdrop for the play.'

Trevelyan still looked puzzled.

âHe's a fan of the ballet, you see.'

âOh.'

âHe cultivates me.'

Carnforth had lent him the key some time ago, when Charles had genuinely needed to work on the backdrop, but he did not know that Charles had had a copy made.

âWhat d'you mean?'

Charles gazed at Trevelyan from under his eyelashes. âMy mother's a famous ballet dancer. Didn't you know? Carnforth thinks if he smarms up to me it'll please her.'

Trevelyan's mouth opened. His father, a wealthy Baptist property developer, took a dim view of theatrical performance in any form. But this unexpected information only added to the hideous excitement he'd experienced during the past half hour.

âYes ⦠darling.' The endearment â daring, unthinkable in this environment â came straight from his mother's world, and the cruelty of it excited him again. He leaned forward and seized the boy quite roughly, pulling his head back and kissing, almost biting, his neck, as he felt for his prick through the coarse flannel of his trousers. The kiss too was unthinkable, almost a kind of blasphemy.

âI'll be so late home.' Trevelyan looked scared now.

âTell them you had an extra art lesson or something.' But Charles's incipient erection subsided. He was bored again. âIt was an art lesson in a way,' he murmured, and smiled to himself. âYou're right, though. We'd better go.'

âSuppose Mr Carnforthâ' and Trevelyan looked round the untidy, battered room. Charles put an arm round the younger boy's shoulders. âGod â you're shivering. Don't worry. I can twist Arthur Carnforth round my little finger. Everything'll be fine.' And he rumpled the boy's hair.

Trevelyan's eyes were as round as saucers. Charles smiled, but didn't enlighten him, other than to murmur languidly something he'd heard Freddie say: âLove takes the strangest forms.' Trevelyan, of course, had no idea what he was talking about.

Charles locked the annexe and slipped the key into his pocket. They walked to the periphery of the playing fields and through the gate, which gave, unexpectedly, onto the main road. Fortunately Trevelyan lived in the opposite direction from Charles, so they didn't have to travel together. To have to make conversation with Trevelyan would have been unutterably tedious. The younger boy scampered across the road, and Charles waited for the bus to Hampstead underground. Emerging at Camden Town, he still felt listless as he walked up Parkway, but he rallied slightly as he remembered it was Thursday and Freddie would probably be there when he got home.

And indeed, he was. He'd brought a red-haired woman friend along as well.

two

R

EGINE MILNER'S SUNDAYS

were casual affairs. She never tidied up in advance. Newspapers and books lay where they fell; and coats were cast over the banisters or left in a heap on the stairs. Bottles and glasses were marshalled in advance, but she didn't bother with extra ashtrays; canapés appeared, if at all, only after several guests had arrived. Informality was still the order of the day three years after the end of the war. But then, as Freddie said, things were never going to get back to how they'd been before 1939. âPre-war' had become merely a sentimental gesture towards a vanished order to which most of Regine's friends hadn't belonged; and bohemian shabbiness â battered antique furniture, Persian rugs unravelling at the edges and balding velvet upholstery â suited this epoch of post-war shortages and making do. And if in the streets and squares of post-war London austerity still dulled the look of everything, in Regine's drawing room the Chinese jars gleamed, the amethyst and sapphire cushions glowed and the crimson walls produced an atmosphere of womb-like warmth in which everyone relaxed.

On this mild autumn day, the first in October, Regine was trying out the new âseparates' idea, teaming a voluminous paisley skirt (made from an old shawl she'd found in the house â it must have belonged to Lydia) with a garnet sweater, and had tied back her tangle of red hair, so curly it fizzed and frizzed round her face, with a green ribbon. Her black suede court shoes, with their old-fashioned square toes, dated from 1942 and had worn to a shine, but that could be passed off as part of the look. And the good thing about the new long skirts was they hid the parlous state of one's precious silk stockings.

Regine's Sundays had begun almost by accident at the end of 1943. She had left the Vale of Evesham and was back in London where she had a new translating job in Whitehall. Once she and Neville were married, it just naturally came about that they opened the doors of his Hampstead house to wartime London's birds of passage. There were so many people in the war who were lonely and unanchored, separated from spouses, bombed out, home on leave, men and women rushing in and out of the capital or searching for lovers, appearing and disappearing. My sitting room's like Waterloo station, she used to say â and Sunday was the ideal day because then everything was shut and boredom could so easily set in.

Now her Sundays were monthly instead of weekly occasions and she could offer her guests gin and sherry again instead of tea, or those home-made brews â gin distilled from potatoes â or dreadful rum concoctions. Nor did she make such an effort these days to give them all something to eat; the cakes and biscuits made from soya flour and the little canapés with fish paste or even dried scrambled egg had dwindled to a few cheese straws and savoury biscuits.

Yet although she sat carelessly with her feet up on the chaise longue, she was as usual a little nervous as she waited for the first arrivals. You never knew whether four or fourteen guests would turn up, indeed she wondered, as she wondered on the first Sunday of every month, whether

anyone

would.

âPerhaps people don't need my Sundays any more. They'd nowhere else to go in the war, but now things are looking up â the theatres open again, the lights going on, life's slowly getting back to normal, isn't it, so â¦'

Neville had already started on the whisky. Without looking up from the

Sunday Times

, he murmured: âKitten â your Sundays are an institution. Our friends

love

coming here.'

Regine stood up and moved restlessly around the drawing room, then sat down again, this time on one of the overstuffed chairs, and looked at her husband, her gaze travelling over the familiar sharp contours of his face, the crimped, receding, mousey hair, and the neat, well-worn suit. None of the arty set's corduroys and tweeds for him; he always looked dapper. From behind his round, steel-framed glasses, his sharp gaze stared out guardedly at the world.

She sometimes felt her gratitude to him for giving her a settled and comfortable life prevented her from knowing him as intimately as she ought, from understanding him as fully as he deserved from a wife. But perhaps he didn't want to be understood, keeping his life in tidy compartments to which only he had the keys.

The door knocker rat-tatted smartly, and she sprang up in relief. But she was disappointed and even irritated to see Muriel and Hilary Jordan on the doorstep. When Regine had first met Hilary during the war, he'd been a cheerily aggressive bohemian with libertarian views, but Muriel had transformed him into a living embodiment of Austerity. Like the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the lantern-jawed Sir Stafford Cripps, Hilary was now an extreme vegetarian who ate only raw food and probably took cold baths. Muriel had strange eyes, like a hawk's, each golden iris encircled by a dark ring. Her hooked nose reinforced the likeness to a censorious bird of prey. She stared at Regine. âWhat a wonderful

ensemble

, very Hampstead,' she said. âHow do you do it on the coupons?'

This was an attack, thinly disguised as admiration. Regine had purchased the coupons from her charlady, but why should she feel guilty? Mrs Havelock needed the money and couldn't afford new clothes anyway.

âOhâ' and Muriel made a darting movement, her finger poked at Regine's cheek, âyour lipstick's smudged.'

Regine recoiled in horror, but managed a smile. âGo and say hallo to Neville, he's holding court in the library.' Though that was hardly an accurate description of Neville behind his newspaper.

âI saw Arthur Carnforth at church this morning,' said Muriel. âWe go to All Saints Margaret Street, you know â very High Church, but I don't like our local vicar ⦠anyway, I said to him, haven't seen you at the Milners' for a long time. He said he might come along.'

Mingled with Regine's dismay at the mention of Arthur Carnforth's name was an awareness, more definite than ever before, that she really disliked Muriel. She said coldly: âYou know quite well he and Neville had a falling out some time ago.' What an interfering, nosy person Muriel was â and the cheek of taking it upon herself to suggest such a thing.

Arthur Carnforth, that grim, awkward man â a failure, a misfit. Regine remembered his clammy handshake, the way he blinked nervously when he talked ⦠Freddie disliked him, although they'd all been friends before the war.

âYes,' said Muriel, unabashed, âbut Neville was very kind to Arthur whenâ'

âWhen he had his breakdown. Yes, I know that.' Regine felt patronised, Muriel's patronising smile infuriated her â as if

she

knew Neville better than his own wife.

Now, though â thank God! â Freddie was in the open doorway. His bulk dominated the crowded little hall. âRegine! Darling!' As if he hadn't seen her for years, when it was only last Thursday.

Arm in arm they swerved into the drawing room and sat down on Regine's great dark green Victorian chaise longue, the pièce de résistance of the room. Freddie had got hold of it for her. Away with all that frightful Moderne rubbish, he'd boomed, enough of ghastly Syrie Maughan white walls and Omega designs, the nineteenth century knew a thing or two about luxury, the more ornament the better.

âSo what did Edith Blake have to say about your latest translation?' he began.

âShe liked it. She's given me a book about tenth-century France to work on now.'

âThat'll give you something to get your teeth into.'

âIt's more likely to break my jaw! I mean, it's nice to have something serious, but the Dark Ages are so depressing.'

âThe Dark Ages ⦠darling, that's what we're having now, isn't it, a post-war Dark Ages.' That was so Freddie â a sombre remark, its sting neutralised by his camp laugh. âThere's something I must talk to you about,' he said, speaking more quietly than usual. âNot now, but perhaps we could have lunch tomorrow. It's quite important. Someone we used to knowâ'

But he was interrupted by another knock on the front door.

âPhil will answer it. Go on. Say what you were going to say. Someone?'

Perhaps it was Arthur Carnforth.

âNo, darling, this isn't the moment. Tomorrow, when I have you to myself.

Now

I must tell you about my marvellous idea. A new ballet magazine. My photographs will be at the centre of it, of course, but I just

know

there's a demand for new writing, more information, something different from the old dance magazines.

God

knows how I'll scrape the money together.' Freddie passed his hand over his fading blond hair. âBy the way â' and he leaned forward so that she caught a whiff of eau de cologne, âVivienne

is

coming â she'll be here any minute â in fact, I'm going to wait for her outsideâ' and he sprang to his feet. Then he paused. âWhat did you think of her house?'

âIt must be dreadfully uncomfortable to live in while it's being restored â but of course it'll be lovely when it's finished. Makes this place seem like a doll's house.'

âThey paid nearly eight thousand for it, you know.

Eight thousand

!'

Freddie had taken her to tea with the ballerina the previous Thursday: âI want my two best girls to get to know each other.' But it hadn't been a success. Vivienne had seemed withdrawn; there'd been little rapport. The only moment of animation had been when her son had turned up as they were all sitting stilted in the middle of her ruin of a house on the canal. The boy had leaned against the door jamb, languidly still and silent so that they'd had to look at him.

âI'm thrilled she's coming. You're marvellous, Freddie.' Vivienne Hallam, or rather Evanskaya â the stage name an adaptation of the mundane Welsh Evans â was certainly a scalp for her salon, as Regine secretly thought of her Sundays, especially as the dancer was quite reclusive, didn't go out much at all. Or so Freddie said.

âI'll wait for her outside,' repeated Freddie. âShe's rather shy, you know.'

Regine strolled away to look for Phil the lodger. Phil was a godsend. Soon he'd be moving around with a tray of drinks, leaving Regine free to devote herself to her guests. And of course it was Phil who'd made sure Cato, their great, bony poodle, was safely shut away upstairs where he couldn't knock over ashtrays with his tail or threateningly rear up on his hind legs in an attempt to hug guests. He'd barked and howled for a bit, but now there was a sulky silence.

By the time Freddie ushered Vivienne Hallam into the drawing room, seven or eight guests had gathered. At this early stage they were bright-eyed with expectancy and a first drink. The space the ballerina's still potent fame created around her brought an almost imperceptible pause as the others recognised her, but too polite to show it, continued their conversations.

She walked as ballerinas did on stage, with feet turned out, like an elegant duck, each step slightly springing. Her son followed behind. Everyone looked at him too.

âMy husband sends his apologies â he's on call this weekend.'

Just as well, Regine thought. Freddie said he was the gloomiest man this side of the Iron Curtain.

âThis is my son, Charles. I didn't introduce you properly the other day.'

The boy shook hands with Regine and as Freddie settled on the chaise longue between his two âbest girls', Charles perched on the arm at his mother's side.

âIsn't he divinely Caravaggio?' whispered Freddie in Regine's ear; then, aloud, he turned towards Vivienne Hallam and said: âNow, darling, about my ballet magazine. You see, it would be marvellous, Vivienne, if we could have something about the company in the war. You were

heroic

, your escape from the Nazis in Holland, travelling about all over England through the Blitz, bringing dance to the people, keeping art going through the darkest days â it was so vital for morale. And it

transformed

ballet from a minor specialised art form into what it is today. Thanks to you everyone

loves

ballet.'

Vivienne Hallam smiled, but to Regine her dark eyes seemed full of melancholy. âI'm not sure John would look at it like that. And it's such a long time ago, Freddie.'

âRubbish â five years, four years. What are you

talking

about! It will be just the thing for the first issue. You have to support me, darling, this ballet magazine is going to be a huge success. There's an audience out there just waiting to adore you all over again â and with my pictures â and the original sketches for the scenery designs â'

âWon't it cost a lot to produce?' enquired Regine. âAnd what about the paper shortage?'

Freddie frowned. âOh, my God â

expense

! I'm trying to scrape the capital together at the moment. Any ideas â and offers of help, of course, are welcome.'

âOh Freddie,' murmured Vivienne, âI don't know â¦'

âI'll get the lolly together somehow, don't you worry. But the main thing will be

you

, your public

demands

it, the first issue a special edition dedicated to you: your memories; an interview; and the photographs, of course. You must come and choose for yourself.'