War of the Whales (9 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

During Balcomb’s first whale-tagging trip aboard the

Lynnann

, January, 1964. From left to right: Captain Bud Newton, Engineer John Dietrich, Dr. Masaharu Nishiwaki, Cook Bob Young, Dale W. Rice (Expedition Leader), Crewman Ernesto Gonzales, and Ken Balcomb.

Lynnann

, January, 1964. From left to right: Captain Bud Newton, Engineer John Dietrich, Dr. Masaharu Nishiwaki, Cook Bob Young, Dale W. Rice (Expedition Leader), Crewman Ernesto Gonzales, and Ken Balcomb.

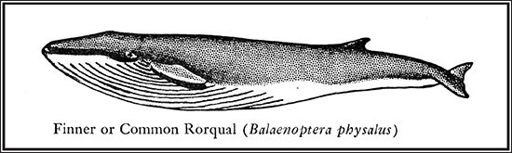

Whale tagging dated back to the 1920s when researchers aboard the British vessel

Discovery

set sail for the Southern Ocean to conduct the first scientific survey of whale migrations. The original

Discovery

“tags” were foot-long stainless-steel cylinders engraved with date, the sponsor’s address, and—in the 1920s—the promise of a cash reward to any whaler who found one while flensing or cooking the whale’s blubber and mailed it back to the researchers in London. Comparing the location of the tagging to the location of its recovery, the researchers could then plot the migration path of the whale.

Discovery

set sail for the Southern Ocean to conduct the first scientific survey of whale migrations. The original

Discovery

“tags” were foot-long stainless-steel cylinders engraved with date, the sponsor’s address, and—in the 1920s—the promise of a cash reward to any whaler who found one while flensing or cooking the whale’s blubber and mailed it back to the researchers in London. Comparing the location of the tagging to the location of its recovery, the researchers could then plot the migration path of the whale.

Forty years later, Rice and Nishiwaki decided to use the same tags and tagging method. But it was harder than they had anticipated. You had to stand on the deck of a fast-moving boat giving chase to a whale that surfaced for just a few seconds to breathe. In that instant, you had to fire the tag from a 12-gauge shotgun and hit the whale. If the tag lodged in the tissue below the blubber layer, you had a successful “mark.” But fired from a distance of 100 to 300 feet, most of the tags missed their target altogether or else hit the dorsal fin and bounced into the ocean.

Ken turned out to be the only person on board who could handle a shotgun well enough to actually make a mark. After a couple of shots, he figured out that the tags were heavy, so you had to aim high to compensate for gravity. And you had to lead the moving target, just as his stepfather Cal had taught him to do while duck hunting. Before dinner of the first day’s tagging, Ken was promoted from dishwasher to marksman/dishwasher. By the end of their two-week tour, he’ d successfully tagged almost 200 whales.

Those two weeks aboard the

Lynnann

were bliss. After years as a loner adrift in his own world, Ken had finally found a peer group and a mission. It was his first time at sea, and he loved everything about it: the boat, the whales, the shotguns, and especially the company of two world-renowned cetologists who knew the answers to all his questions about whales.

Lynnann

were bliss. After years as a loner adrift in his own world, Ken had finally found a peer group and a mission. It was his first time at sea, and he loved everything about it: the boat, the whales, the shotguns, and especially the company of two world-renowned cetologists who knew the answers to all his questions about whales.

During that tagging trip, Ken began photographing whales. He’ d been taking nature photos ever since high school, and shortly before the tagging trip Ken had seen a spectacular photo-spread of humpback whales in

Life

magazine.

1

At the time, almost no one had photographed whales in the wild. Fortunately for Ken, the same keen eyes and quick reflexes that made him a good whale tagger enabled him to capture photographs of whales from the deck of the

Lynnann

.

Life

magazine.

1

At the time, almost no one had photographed whales in the wild. Fortunately for Ken, the same keen eyes and quick reflexes that made him a good whale tagger enabled him to capture photographs of whales from the deck of the

Lynnann

.

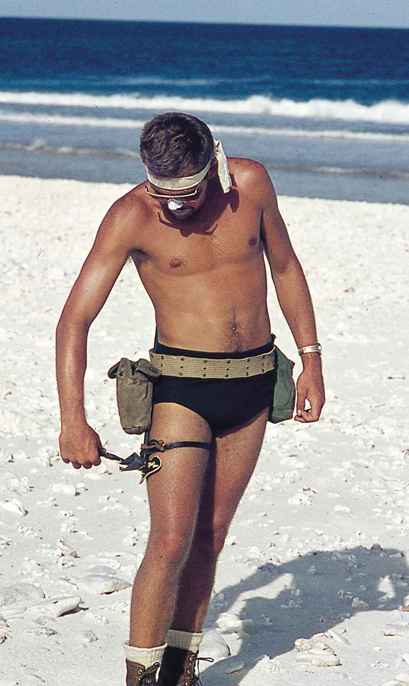

Aboard the

Lynnann

, armed with a whale-tagging shotgun and a camera.

Lynnann

, armed with a whale-tagging shotgun and a camera.

By the end the trip, Rice offered Ken the job of expedition leader on another tagging trip over the summer. When Ken returned home, triumphant, Anne wasn’t there to celebrate. She’ d taken their one-year-old son, Kelley, and moved back with her parents in Sacramento. Ken begged her to come home, but she refused. She knew that Ken was doing what he’ d always wanted, but it wasn’t what she’ d signed up for. She missed the clean-cut kid with the winning smile she’ d met at the gas station. The one who was heading to law school, not the one who hung out in whale processing plants, who went to sea for weeks at a time and came home smelling like a fishmonger.

Ken was crushed that his young family was breaking apart. A month later, when Anne began seeing a medical student across campus, Ken couldn’t handle it. He dropped out of grad school and took a volunteer job with Dale Rice tagging whales. After a series of trips marking gray whales in Baja, Rice offered him a full-time job working for the US Fish and Wildlife Service. So Ken moved to Berkeley and worked at the Richmond whaling station collecting specimens. Day after day he searched for Discovery tags in the piles of offal and in the cookers, verified the length and legality of the catch, and took samples of their blubber, earwax, stomach contents, and gonads.

His divorce papers arrived that spring. Two months later, he heard from the draft board. Now that he was neither married nor a student, Ken was reclassified as 1-A eligible. It was the summer of 1965, and troop levels in Vietnam were escalating rapidly. Dale Rice suggested a “deferred occupation” that might keep the draft board at bay. The Smithsonian was directing a contract job for the US Army, banding birds in the Pacific, based out of Honolulu. All things considered, the middle of the Pacific Ocean sounded to Ken like a pretty good destination.

2

2

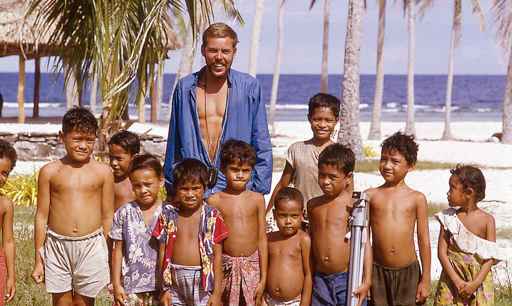

Ken spent a year at sea, moving from dot to dot in the central Pacific and the Hawaiian island chain. From there, he progressed to a seemingly endless string of central and South Pacific atolls. Every few days, he would disembark from the mother ship aboard an inflatable boat packed with a tent, food, and water, and thousands of aluminum leg bands. He’ d find landfall, set up camp, sleep all day, and work all night banding birds that nested on the ground along the shore.

Bird banding on Hull Island in the North Pacific, 1966.

It was classic stoop labor, like planting rice in a paddy. Insects feasted on his arms and legs. Coral sliced his feet and ankles. It was the kind of work that only a masochist, or a man in flight from his mainland life, could tolerate. If it felt a bit like working on a chain gang, that suited Ken too. He felt guilty for making a mess of his family life and for being an absentee father, as Blue had been.

While bird banding on Swain’s Island near American Samoa, 1966.

Then, in August 1966, when his ship was crossing the equator precisely at the international date line, a message came over the ship’s Teletype from Dale Rice: “Sorry, Ken, the draft board rejected your deferral. Report for immediate induction at first US landfall.”

When he returned to Berkeley, Ken crashed with his half brothers, Howie and Rick. In the year Ken had been at sea, the Bay Area had become the epicenter of the antiwar movement. Flower power was in full blossom. Rick had joined the US Navy reserves in college, and Howie, also 1-A eligible, was moving to Canada to escape the draft. But Ken didn’t want to run away to Canada. He wasn’t antiwar or antimilitary. Rather than waiting to be drafted into the infantry—which seemed to him like a death trap—Ken decided to apply to the same Naval Aviation Corps that the colonel’s son had served in before his fatal crash. Despite the colonel’s scorn and abuse, Ken still wanted his stepfather to think he’ d amounted to something.

Ken showed up for basic training in Pensacola, Florida, with long, raggedy hair and a beard, looking like an island castaway crossed with a Berkeley hippy. They gave him the standard issue high-and-tight crew cut, then sent him through the

Top Gun

indoc routine: break you down and build you back up to fit the mold. By the seventh day of indoc, he was ready to quit. Then he started to notice that he was doing better than his classmates, who were mostly three or four years younger. The push-up and sit-up drills were nothing compared to what he’ d endured during his year of bird banding. And he could still clock the fastest mile in his squadron.

Top Gun

indoc routine: break you down and build you back up to fit the mold. By the seventh day of indoc, he was ready to quit. Then he started to notice that he was doing better than his classmates, who were mostly three or four years younger. The push-up and sit-up drills were nothing compared to what he’ d endured during his year of bird banding. And he could still clock the fastest mile in his squadron.

In flight training, Ken learned aviation and aeronautics and how to shine his shoes. He grew to appreciate the Navy’s merit system. You learned your shit and did your job, and you got recognition. After 12 weeks, he graduated first in his class.

Every Navy flyboy worth his salt had to get himself a blonde and a Corvette after being commissioned an officer. Ken had no quarrel with that directive. As a connoisseur of vintage cars, he passed on the Corvette and bought himself a ’57 Mercedes Gullwing. He never loved a car like he loved that one. Blondes were even easier to come by. It seemed that every girl from New Orleans to Tallahassee would show up in Pensacola on the weekends to try to snag a flyboy. Julie Byrd was from Mobile, Alabama. She followed Ken to advanced flight training in Corpus Christi, Texas, and they got married in Norfolk, Virginia, where he was assigned to the air group at the naval base. Julie didn’t want kids, which suited Ken just fine. She was a go-along-get-along kind of girl, a useful quality in a Navy wife.

Ken’s second wife, Julie, pinning on his naval aviator “wings” after graduation from flight school in Corpus Christi, Texas, August 1968.

After he completed advanced flight school in the top 1 percent of his class and got his “wings,” Ken submitted his “dream sheet” for his first assignment. He wasn’t keen to pilot bombing runs over Vietnam. His first choice was to fly research aircraft, either as a hurricane hunter or to supply expeditions in Antarctica. His second choice was fixed-wing antisubmarine surveillance.

So what assignment did he draw? Airborne Warning and Control System, or AWACS, what he considered the most boring flight job in the sky! You take off from a carrier and fly racetrack ovals while the guys back in air traffic control look for bogies on your radar screens. He’ d flown AWACS for a week during flight training, and it bored him to death. He couldn’t believe it. He’ d finished at the top of his class, and he’ d drawn AWACS duty?

Ken applied for an assignment change. He begged for a research job—any kind of research. So they assigned him to oceanographic research and sent him to Fleet Sonar School in Key West, Florida. For a Navy flight officer, sonar was a total dead end. It wasn’t even a flight assignment. He figured it was retaliation for refusing AWACS. But at least it would get him back to sea, or at least seaside.

What Oceanographic Officer Ken Balcomb didn’t realize was that naval sound surveillance would offer him a privileged porthole into the hidden world of whales.

Other books

Niv: The Authorized Biography of David Niven by Graham Lord

The Spy Who Saved Christmas by Marton, Dana

Bride Quartet Collection by Nora Roberts

No Man's Land by Pete Ayrton

Match Play by Merline Lovelace

A Santangelo Story by Jackie Collins

Rupture: Rise of the Demon King by Milo Woods

After the Dark by Max Allan Collins

Sleigh Bells in Valentine Valley by Emma Cane

Gently with the Ladies by Alan Hunter