War of the Whales (7 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

The crevice between the skull and the first cervical vertebra is curved, so he had to work the blade at an angle until he found the precise seam, and then pivot it back and forth like a clam knife until the spinal cord gave way. It was quick work to slice through the cranial nerves and the network of arteries that feed oxygenated blood to the brain. As the blood poured out of the whale’s neck, Balcomb was grateful that at low tide the lagoon was too shallow to attract sharks.

Balcomb cutting off the head of a Blainville’s beaked whale at Cross Harbor to preserve an evidence trail of the mass stranding.

Balcomb worked deep inside the carcass, more by touch than by sight. He pushed the blade through the soft tissue of the esophagus, and then past the cartilage and other connective tissue of the larynx and the windpipe. There was only a half foot of muscle and blubber below the throat. Deftly avoiding the hyoid bone collar at the base of the throat, Balcomb completed his cut, and the head hinged away from the carcass like a stout felled tree.

“Bravo,” Claridge said softly as she lowered the video camera from her shoulder and stooped to admire the specimen. Balcomb was pleased by what a clean cut he’ d made, and by how well articulated and intact the vascular structures had remained. For a bone hunter like Balcomb, a beaked whale skull is the rarest of trophies. If it hadn’t been a vital piece of forensic evidence, he’ d have buried the head deep in the sand and let the underground beetles and sand flies pick the cranium clean over the next few weeks. Then he’ d place the treasure on the high shelf at the beach house, alongside the other two

Ziphius cavirostris

(beaked whale) skulls he’ d collected in four decades of beachcombing.

Ziphius cavirostris

(beaked whale) skulls he’ d collected in four decades of beachcombing.

A beaked whale’s head tells the entire tale of its remarkable evolution. Its cranium is almost twice as thick as a dolphin’s, the better to withstand extreme water pressure at depth. Its dense, beaked rostrum is both a powerful weapon against mate-competing males and a potent defense against sharks. The beaked whale’s sound-emitting powers originate in its nasal cavities, which transmit both communication sounds and sonar clicks. Its concave forehead cradles an acoustic lens, or melon, that focuses sound into different beam forms. Its long jawbone conducts return echoes and incoming communications from other whales to the three small ear bones common to all mammals, which are nested well back in its head. Elaborately convoluted, with an enormous auditory cortex, the beaked whale’s brain is a masterpiece of signal processing. It can conduct multiple conversations simultaneously, as well as translate biosonar echoes into exquisitely detailed, three-dimensional maps.

As far as Balcomb was concerned, the beaked whales of Great Bahama Canyon were the niftiest piece of biotechnology ever engineered. Ever since he was a kid, he had taken things apart so he could study their design, then put them back together. He was a connoisseur of well-made machines: cars, boats, planes. To hear his wives tell it, Balcomb was an incurable tightwad who never wanted to spend a dime on clothes or restaurants or home improvement. But back at Smugglers Cove, he kept a half dozen mint-condition classic and vintage cars parked in makeshift garages on the grounds around his house.

Spattered with sweat and sand and bits of flesh, Balcomb knelt in the sand and stared at the decapitated Blainville’s. All that magnificent engineering, he thought, couldn’t save this whale from whatever the hell had happened in the canyon.

While two Earthlings videotaped and took photographs, Balcomb, Claridge, and Ellifrit went to work collecting tissue specimens. They took samples of the blubber, lungs, heart, kidney, and intestines. A beaked whale’s liver, the size of a large shoulder bag, is usually the first organ to rot. But Balcomb was reassured to find that this one was still firm and fresh. They washed each specimen with acetone, wrapping several slices in aluminum foil and fixing others in formalin.

Though he was normally laconic, Balcomb gave the Earthlings a running anatomy tutorial on the Blainville’s beaked whale he was dissecting. He explained that a Blainville’s is smaller than a Cuvier’s, and that it’s also called a dense-beaked whale, because its beaked rostrum is the densest bone found in any animal. He showed them the specialized lipids in the blubber and the vascular plumbing in the fin, flukes, and flippers that keep a whale from overheating in the warm surface waters. He explained the overbuilt

retia mirabilia

, or “wonderful network” of veins and arteries that engorge during deep dives to conserve core body heat and allow the gradual reabsorption of respiratory gas in the blood on ascent. He opened up each of the beaked whale’s 13 stomachs, designed for efficient food storage and digestion during long dives, and carefully catalogued the half-digested squid he found there. Balcomb divided the specimens into two batches—one for US Fisheries, and one as backup in case the Fisheries’ specimens went missing.

retia mirabilia

, or “wonderful network” of veins and arteries that engorge during deep dives to conserve core body heat and allow the gradual reabsorption of respiratory gas in the blood on ascent. He opened up each of the beaked whale’s 13 stomachs, designed for efficient food storage and digestion during long dives, and carefully catalogued the half-digested squid he found there. Balcomb divided the specimens into two batches—one for US Fisheries, and one as backup in case the Fisheries’ specimens went missing.

When they were finally done, they loaded the head into the back of the pickup and raced to Nancy’s. There was room inside Les’ freezer to nestle the Blainville’s head atop the dolphin. Balcomb would have loved to grab a beer on Les’ back porch, but he needed to get back aloft and continue the aerial search, and there was less than an hour of sunlight left.

• • •

The sun was setting behind the plane as Anspach headed east toward Tilloo Cay. The bay was empty of fishing boats now. A lone catamaran tacked into the late-day wind. To look down on this postcard panorama, it was hard to imagine that just a day earlier something had gone horribly wrong inside the canyon.

“What’s that, coming around the point?” Anspach shouted over the engine noise. He motioned to a ship emerging from behind a small cay, about a mile to the south. “A trawler?”

Balcomb swung his binoculars around to the pilot-side window. It was too big for a fishing trawler. To judge by its length and blue-gray color, it was military.

“Let’s take a closer look,” said Balcomb. “But not too close.”

Anspach banked the plane to the left and circled, giving the vessel a wide berth. Once he got a side view, it was easy for Balcomb to ID the ship. It was a destroyer, with US Navy markings. Through the viewfinder of his video camera, he could clearly make out the antiaircraft guns mounted on its foredeck. He checked the plane’s instrument panel to confirm that they were safely outside the warship’s no-fly radius.

“Don’t go any closer,” Balcomb said to Anspach, as he shot stills through his longest lens.

6

6

There was nothing subtle about a modern naval destroyer, Balcomb mused as he peered at the rows of guided-missile batteries and antisubmarine rocket launchers. Its name pretty much said it all. He knew that destroyers rarely sailed alone, that they usually ran escort for a full battle group. So, where were the other ships? A more urgent question pressed against his brain, and his heart: What was a US Navy destroyer doing in Great Bahama Canyon?

Balcomb didn’t share any of these questions with his friend. In the 25 years since he’ d worked undercover for the Navy, Balcomb had never spoken to anyone about the details of his military service. If you were involved in classified work, you didn’t talk about it to civilians. Period. Those were the rules of his security clearance, and he’ d always remained faithful to his oath of secrecy. Even inside his marriages—including his marriage to Diane.

* Dolphins are small whales whose neurology, physiology, and biosonar resemble other “toothed” whales.

4

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Beachcomber

1943

Albuquerque, New Mexico

There had always been a lot of military in Ken Balcomb’s family. Just not much family.

His first memory, at age three, was of hugging a soldier good-bye and pressing his face into the jacket of his uniform. The soldier who knelt in front of him was leaving for Marine Corps officer training school before shipping out to fight the Japanese in the South Pacific. Ken cried and held the soldier tight. Then the soldier began to cry, too.

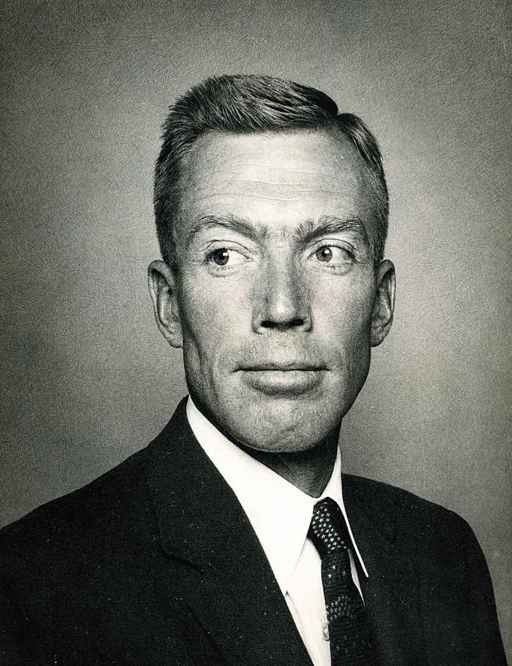

Ken Balcomb’s family in 1942 (

left to right

): his uncles Douglas and Edward Balcomb; his grandmother Katherine; Ken at age one and a half; his father, Kenneth, Jr. (known as “Blue”); his grandfather Kenneth, Sr.; and his uncle Robert.

left to right

): his uncles Douglas and Edward Balcomb; his grandmother Katherine; Ken at age one and a half; his father, Kenneth, Jr. (known as “Blue”); his grandfather Kenneth, Sr.; and his uncle Robert.

Ken’s father survived the war, but he never returned to his wife and son in New Mexico. Instead, he married a Wave he’ d met during training and started a new family with her in Colorado. He never wrote to Ken; never called on his birthday. Growing up, Ken’s only memento of his father was a framed studio photo of a handsome, well-groomed man in a suit and tie. Everyone called him “Blue” because of his piercing blue eyes. But the photo was black and white, so Ken could only guess if his father’s eyes were the same shade of blue that stared back at him from the mirror.

Ken’s father, Kenneth “Blue” Balcomb, Jr.

Ken’s mother, Barbara, refused to mention Blue by name. So Ken had to mine nuggets of information about his father from his grandfather and uncles. Blue and Barbara had met at the University of New Mexico where she was studying music. Blue was restless in college, and when Ken was born shortly after he married Barbara, he dropped out of school and took a job as a pipefitter laying gas lines. As soon as the war broke out, Blue enlisted in the Marines. Barbara was furious at him for leaving her alone with an infant, since he was eligible for a family exemption from the draft.

Once it became clear that Blue wasn’t coming home, Barbara moved on to her next husband. And the next, and the next. Whether they were warm to him or indifferent, Ken reached out to each of his stepfathers as they passed by, as if he were floating down a river and grasping at exposed tree roots along the banks.

First there was Robert Garrett, a debonair pilot from nearby Kirkland Air Force Base. He and Barbara would take Ken to the officers’ club with them, and give him a bag of nickels to play the slot machines, while they drank and danced the night away. They divorced a few years later, shortly after Barbara gave birth to Ken’s half brothers, Howie and Rick.

Other books

Before the Dawn by Kate Hewitt

Powers by Ursula K. le Guin

Rites of Spring by Diana Peterfreund

Highland Shifter (MacCoinnich Time Travel) by Catherine Bybee

Murder in the Monastery (Libby Sarjeant Murder Mystery series) by Cookman, Lesley

The American Bride by Karla Darcy

When Will There Be Good News? by Kate Atkinson

The Other Barack by Sally Jacobs

Nobody Does It Better by Ziegesar, Cecily von

His Promise (Married in Montana Book 1) by Eckhart, Lorhainne