War of the Whales (2 page)

Authors: Joshua Horwitz

As they rose to top predator on land and at sea, humans turned their technological zeal to weapons of war, spurring an arms race without end. In the twentieth century, submarine weaponry evolved from primitive torpedoes to intercontinental ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads. Like their cetacean counterparts, submariners lived and died by their ability to navigate and hunt acoustically in the black depths of the oceans.

In the early hours of March 15, 2000, the paths of the world’s most powerful navy and the ocean’s most mysterious species of whales were about to converge. Though on the calm surface of the Great Bahama Canyon, nothing hinted at anything amiss. It was just another morning in paradise, the day the whales came ashore.

PART ONE

STRANDED

I have met with a story which, although authenticated by undoubted evidence, looks very like a fable.

—Pliny the Younger,

Letters

(on hearing reports of a boy riding on the back of a dolphin in the first century AD)

Letters

(on hearing reports of a boy riding on the back of a dolphin in the first century AD)

1

The Day the Whales Came Ashore

DAY 1: MARCH 15, 2000, 7:45 A.M.

Sandy Point, Abaco Island, the Bahamas

Powered by his second cup of coffee, Ken Balcomb was motoring through his orientation speech for the Earthwatch Institute volunteers who had flown in the night before. The workday started early at Sandy Point, and Balcomb was eager to finish his spiel and head out onto the water before the sun got high and hot.

“Take as many pictures as you like,” he told them, “but leave the marine life in the ocean. Conches in the Bahamas are listed as a threatened species, so you can’t take their shells home as souvenirs.”

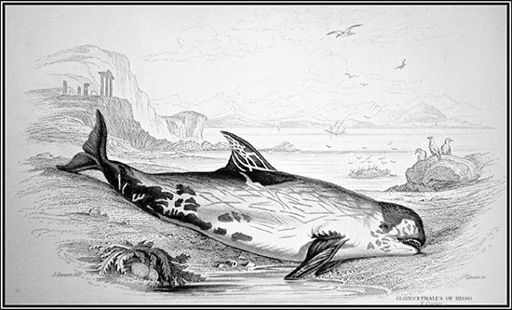

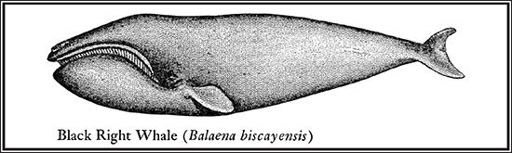

After a breakfast of sliced papaya and peanut butter sandwiches, a dozen volunteers sprawled across the worn couches of the modest beachfront house that Balcomb rented with his wife and research partner, Diane Claridge. Here, on the underpopulated southwestern tip of Abaco, far from the posh resorts on the tiny Out Islands elsewhere in the Bahamas, the only tourist activity was bonefishing in the clear, bright shallows of the continental shelf. What the tourists rarely glimpsed, and what the volunteers had come to see, were the reclusive Cuvier’s and Blainville’s beaked whales of the Great Bahama Canyon.

For the past 15 years, the Earthwatch volunteer program had provided the sole financial support for the decadelong photo-identification survey of the beaked whales here in the Bahamas and of the killer whales in the Pacific Northwest. The Earthlings, as Ken and Diane called them, traveled from across the United States and around the world to assist their survey and to catch a fleeting glance of the deepest-diving creatures in the ocean: the beaked whales that lived inside the underwater canyon offshore from Sandy Point. For the most part, they were altruistic tourists, from teenagers to golden-agers, looking for a useful vacation from the winter doldrums up north. At Sandy Point, they could learn a little about whales, lend a hand in a righteous eco-science project, and enjoy the Bahamian sunshine.

Earthwatch volunteers set out to observe beaked whales off of Abaco Island.

Occasionally, one of the volunteers got hooked on the research and never went home. While still a teenager in landlocked Missouri, Dave Ellifrit had seen Balcomb’s photos of killer whales in a magazine. That summer, he showed up at Smugglers Cove on San Juan Island, off the coast of Washington, to help with the annual survey. Ellifrit was immediately at home with the open-boat work, despite the pale complexion that came with his bright red hair. Fifteen years later, he was still working for room and board as a year-round researcher—at Smugglers Cove in the summer and at Sandy Point in the winter. Balcomb and Claridge had more or less adopted the young man, mentoring him in whale research and helping pay his way through an environmental science program at Evergreen State College in Washington.

While Balcomb finished briefing the Earthlings on the details of photo identification and log entries, Ellifrit was on the beach readying the motorboats for the day’s survey. “Don’t be disappointed if you don’t see any beaked whales your first day out,” Balcomb explained to the volunteers. “They range all over the canyon and surface only about once an hour, rarely in the same place twice. So unless you get lucky, you won’t be grabbing any photos at first.”

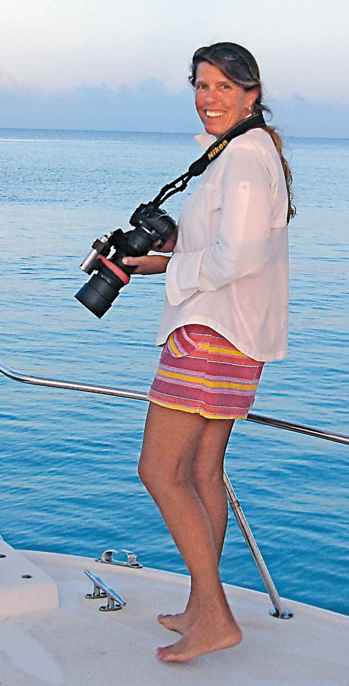

Diane Claridge on the lookout for marine mammals in the Great Bahamas Canyon, where she and Ken Balcomb studied the beaked whale population from 1991–2000, and where she continues to conduct research.

Balcomb explained the differences between the Cuvier’s and Blainville’s beaked whales that he and Claridge had catalogued over the past decade. Some of the more studious Earthlings took notes. Others were busy applying an extra layer of sunblock, which was fine with Balcomb. He didn’t want to spend his evening nursing sunburned volunteers.

Ken Balcomb on his porch in Smugglers Cove, San Juan Island, Washington. He has conducted an annual summer survey of the resident orca community since 1976.

Balcomb had the weather-beaten look of someone who’ d spent most of his six decades on the water, and about ten minutes focused on his wardrobe. Every morning, he pulled on whatever free promotional T-shirt he’ d fished out of the pile in his closet and stepped into a nondescript pair of sun-bleached shorts and the flip-flops he’ d stepped out of the night before. He wore his hair shaggy or cropped short, depending on how recently Diane had taken the shears to him, topped off by whatever baseball cap the last group of Earthlings had left behind. Balcomb’s face was mostly covered by a thick salt-and-pepper beard, and his bright, constantly watchful eyes had the reverse-raccoon look that comes from wearing sunglasses 12 months a year.

Even standing in the living room, he kept his legs planted in the wide stance of a man accustomed to life on boats, flexed just enough to absorb any unexpected pitch or roll. “There are only a few dozen whales in the whole canyon, and some weeks we only see a handful of them,” he continued. “But there’s lots of other marine life out there if you keep your eyes peeled.”

A college-aged young woman raised her hand. “What do we do about the sharks?”

“The sharks are nothing to worry about unless there’s blood in the water,” Balcomb said with a smile. “So any of you women . . .” Claridge winced in anticipation of an off-color punch line she’ d heard too many times. Balcomb liked to tease his beautiful Bahamian wife about her British reserve, and he couldn’t resist trying to bring a blush to her pale, almost Nordic face. “. . . if it’s your time of month, you might want to stay in the boat, because—”

The screen door banged open. Everyone looked up to see Dave Ellifrit, out of breath and wide eyed. When his eyes found Balcomb’s, he said, almost matter-of-factly, “There’s a whale on the beach.”

Claridge grabbed the camcorder off the kitchen counter and raced out the door. Balcomb jogged down the beach behind her, slowing to a walk as he reached the water’s edge.

The whale lay helpless in three feet of water, its spindle-shaped body lodged in the sand, while its tail fluke splashed listlessly in the shallows.

Balcomb couldn’t believe how close to the house the animal had stranded: less than 100 feet up the beach. It was a Cuvier’s—and it was alive. A live Cuvier’s beaked whale! How was that possible? His mind raced to fix on a reference point. The last beaked whale to strand alive in these waters had come ashore decades ago, back in the early 1950s, on the north side of the island.

Balcomb had been chasing after various species of beaked whales for most of his life.

*

As a teenaged beachcomber in California, he’ d thought of beaked whales as emissaries from the distant past: modern dinosaurs that jealously guarded the secrets of their evolutionary journey from the Eocene Age. He’ d walked countless miles of coastline in search of bone fragments, hoping to piece together small skeletal sections, waded knee-deep through piles of discarded organs outside whaling stations on four continents, searching for some anatomical prize tucked away inside—a tusk or a vertebra or, the rarest of treasures, a skull. In his twenties, he’ d begun photographing beaked whales during whale survey expeditions in the Pacific. For a dozen winters, he’ d sailed a tall ship along the Atlantic Seaboard, charting whale migrations and searching for beaked whales from Newfoundland to the Dominican Republic.

*

As a teenaged beachcomber in California, he’ d thought of beaked whales as emissaries from the distant past: modern dinosaurs that jealously guarded the secrets of their evolutionary journey from the Eocene Age. He’ d walked countless miles of coastline in search of bone fragments, hoping to piece together small skeletal sections, waded knee-deep through piles of discarded organs outside whaling stations on four continents, searching for some anatomical prize tucked away inside—a tusk or a vertebra or, the rarest of treasures, a skull. In his twenties, he’ d begun photographing beaked whales during whale survey expeditions in the Pacific. For a dozen winters, he’ d sailed a tall ship along the Atlantic Seaboard, charting whale migrations and searching for beaked whales from Newfoundland to the Dominican Republic.

For the past ten seasons, he and Claridge had staked out a “species hot spot” in the Great Bahama Canyon, waiting with loaded cameras in small boats to photograph and videotape, classify and catalogue the resident community of Cuvier’s and Blainville’s beaked whales. But until the morning of March 15, 2000, he had never touched a live beaked whale. And now, right at his feet, lay a living, breathing specimen. For a hardcore bone-hunting beachcomber like Balcomb, this was an embarrassment of riches. An intact beaked whale that could provide a window into its functional anatomy, and a complete skeleton!

Other books

Savant by Rex Miller

Vampire Academy by Richelle Mead

The Paper Magician by Charlie N. Holmberg

Spinning Starlight by R.C. Lewis

The Pleasure of My Company by Steve Martin

Ruby by Cynthia Bond

Death Along the Spirit Road by Wendelboe, C. M.

Making the Hook-Up by Cole Riley

Other Earths by edited by Nick Gevers, Jay Lake

Enid Blyton by Barbara Stoney