War: What is it good for? (32 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

The most difficult kinds of men to standardize were officers. The new system needed lots of them (Dutch armies shifted in the 1590s from companies of 250 soldiers with 11 officers to companies of 120 men with 12 officers, and the ten-to-one ratio remains standard to this day), but the obvious men for the jobâthe upper classesâtended to see themselves as aristocrats first and cogs in a machine a very distant second. “Our lives and possessions are the king's. Our soul is God's. Our honor is our own,” one French officer wrote. Junior officers regularly dueled with their superiors over arcane points of etiquette, and being squeezed into uniforms that subsumed their individuality into standardized ranks struck most as a deep insult.

Well into the eighteenth century, officers dressed for battle as they would for a ball, in powdered wigs, buckled shoes, and satin breeches, trailing clouds of perfume. “Dear me,” the heroine of one eighteenth-century comedy remarked, “to think how the sweet fellows sleep on the ground, and fight in silk stockings and lace ruffles.” (At the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745, one French officer brought along seven spare pairs of silk stockingsâjust in case.) Not till 1747 did a group of young British naval officers, meeting secretly at a coffeehouse, hit on the idea “that a uniform dress is useful and necessary for the commissioned officers.”

Sartorial anarchy aside, though, newly created military academies did start forging fairly professional officer classes after 1600. Samuel Pepysâdiarist, man-about-town, and master administratorâoverhauled English

1

naval training in 1677 and was clear about the goal: to produce officers of “sobriety, diligence, obedience to order and application to the study and practice of the art of navigation.” With the possible exception of sobriety, he succeeded brilliantly, forcing every officerâno matter how well connectedâto pass examinations in astronomy, gunnery, navigation, and signaling.

By 1700, the lines of fire that Europeans deployed on land and sea were unquestionably the most ferocious the world had ever seen. Their one weakness, Pepys observed, was “the want of money, [which] puts all things, and above all things the Navy, out of order.” Keeping up with the arms race in standardized men and cannons was staggeringly expensive. Even in the

richest states, there was never enough money, and matching means and ends soon became the greatest challenge for governments.

The crudest solution was to cook the books. Governments blithely defaulted on debts, let inflation run riot, and, when all else failed, simply stopped paying their troops. That, however, usually went badly. Unpaid English sailors invented the concept of going on strike, literally striking their ships' sails so the fleet could not move until the government paid up. In 1667, with the fleet on strike and Pepys unable to work because of the “moan of the poor seamen that lie starving in the streets for lack of money,” a Dutch fleet sailed up the Thames and burned or towed away England's best ships. Sailors' wives laid hands on members of Parliament in the streets of London, shrieking, “This is what comes of not paying our husbands!”

The alternative to lowering the costs of war was raising more revenues to pay for it, and governments pursued this tack even more vigorously. One technique, known as absolutism, involved sweeping away the clutter of privileges that nobles, cities, and clergymen had accumulated over the previous thousand years and allowing monarchs to tax everything in their realms. Naturally, this appealed strongly to kings, but those whose privileges were being swept away were less happy. All too often, the result was civil war.

When things went badly for kings, as they did in England in 1649 and France in 1793, they might end up losing their heads. But even when things went well, there was still never enough money. Not even France's Louis XIV, the greatest of the absolutists (who reputedly came up with the catchphrase

l'état, c'est moi,

“the state is me”), could actually raise enough money to batter all the kingdoms that combined to oppose him into submission. At his death in 1715, France was almost bankrupt.

A third approach was to mobilize money more efficiently. Here the Dutch led the way, creating a secondary market for government bonds. This allowed capitalists to buy pieces of the national debt, then sell them, along with the interest they paid, to other investorsâmuch as banks today make mortgage loans and then sell them on. In combination with laws that soothed investors' fears about sovereign default, this gave Dutch governments the ability to raise more money, faster and cheaper than any rivals. The Dutch fought constantly in the seventeenth century, and their debt ballooned from 50 million guilders in 1632 to 250 million in 1752, but thanks to investor confidence the interest they paid steadily fell, dipping under 2.5 percent in 1747.

In 1694, England took this idea further, opening a national bank to

manage the public debt and allocating specific taxes to pay interest on bonds. Sound public finance brought in extraordinary amounts of money; while a single major defeat could bring nations with poor credit to their knees, governments in Amsterdam and London seemed able to raise, drill, and commit new fleets and armies almost at will. To the English novelist Daniel Defoe, it felt as if “credit makes the soldier fight without pay, the armies without provisions.”

Governments could hardly ask for more than this, yet most remained ambivalent about the new institutions. Then as now, financial instruments that looked wonderful to bankers could look alarming to everyone else, and then as now hardly anyoneâincluding bankersâactually understood how the new tools really worked. In 1720 the South Sea Bubble in Britain and the Mississippi Bubble in France brought banks crashing down and left investors ruined. A Tea Partyâstyle backlash set in, and although the eighteenth century had nothing quite like Wall Street versus Main Street, it did have Threadneedle Street (the Bank of England's address) versus the country estate. Aristocrats who had dominated politics for generations suspected (rightly) that business-friendly governments might leave them worse-off, and kings found it hard to give up the plunder-and-spend policies that had worked for them in the past.

The most constructive solution to the problems of funding fighting, however, came not from cooking the books, raising extra revenue, or mobilizing money more effectively but from putting the paradox of war to work. Kings trimmed back their increasingly lethal forces but wove webs of alliances to share the costs of campaigns. The result was something of a balance of power, raising the price of aggression (if a government upset the balance, others would band together to restore it) and lowering the price of survival (if one state was threatened with destruction, others would rescue it to keep the balance intact).

Paradoxically, because armed forces were now so deadly, the amount of killing they did declined. To avoid provoking hostile coalitions, rulers limited their wars, defining aims narrowly and using force carefully. Battles remained as gruesome as ever (in 1665, England's Duke of York was knocked off his feet by the detached head of the Earl of Burlington's second son), but warsâwhich European writers started calling

Kabinettskriege,

or “ministers' wars”âgrew more orderly. “No longer is it nations which fight each other,” a French politician observed in the 1780s, “but just armies and professionals; wars are like games of chance in which no one risks his all; what was once a wild rage is now just a folly.”

In the classic case, seven European governments came together in a grand alliance in 1701 to stop the crowns of France and Spain from landing on a single royal head. Uniting Paris and Madrid would have created a superpower, shattering the balance; so, for a decade, volleys and broadsides blasted from Blenheim to Barbados to prevent this from happening. By 1710, the alliance clearly had the upper hand, but some of its members started worrying that crushing France and Spain would tip the balance of power too far in Britain's favor, so they switched sides to even things out. The fighting finally petered out in 1713â14.

Judged just by what was happening in western Europe, the coming of guns and the closing of the steppes had not been very productive at all. While it had freed Europe from the long cycle of productive and counterproductive wars by giving it the weapons to defeat the steppe horsemen, it had not revived productive war in the same way as had happened in Asia, where great new continental empires had formed since 1500. Western Europeans seemed bogged down in unproductive war, in which kings and their cabinets besieged fortresses and exchanged frontier provinces but neither productively built up nor counterproductively broke down larger societies.

The War on the World

The three hundred years of war between 1415 and 1715 did little to change the map of western Europe, but they turned much of the rest of the globe upside down. Europe's conflicts spilled out across the oceans, and Europeans drifted into waging a war on the world. From Portugal to the Netherlands, rulers on Europe's Atlantic fringe grew very keen on overseas activity that they could tax, spending the gains on wars at home. The money that poured in paid for much of Europe's military revolution, and the military revolution in turn gave Europeans the weapons that made overseas expansion possible.

Cannons gave fifteenth-century sailors naval superiority everywhere they went and worked wonders for focusing the minds of reluctant trading partners. When haggling could not convince merchants in Mozambique and Mombasa to sell him supplies in 1498, Vasco da Gama found that gunfire could, and when Pedro Ãlvares Cabral reached India two years later (discovering Brazil along the way, when he sailed a little too far into the Atlantic while trying to get around Africa), his bombardment of Calicutâkilling five hundred peopleâopened its markets promptly.

By 1506, Portugal had formulated a breathtakingly ambitious plan, elevating piracy to the level of grand strategy. Every ship trading in spices had to use a few key ports; so, Portuguese sailors reasoned, by shooting up and seizing Hormuz, Aden, Goa, and Malacca, they could turn the Indian Ocean into a private lake and tax every ship on it. Portugal would be rich beyond the dreams of avarice.

The plan almost, but not quite, came off. Part of the reason was military; because Portugal never managed to take Aden, Arab traders went on entering the Indian Ocean without paying duties. But the bigger problem was that there was more to overseas expansion than just winning battles. Four other forcesâdistance, disease, demography, and diplomacyâhad as much to do with the outcome as did devastating firepower. How well Europeans fared in any part of the world was a function of the balance between these forces.

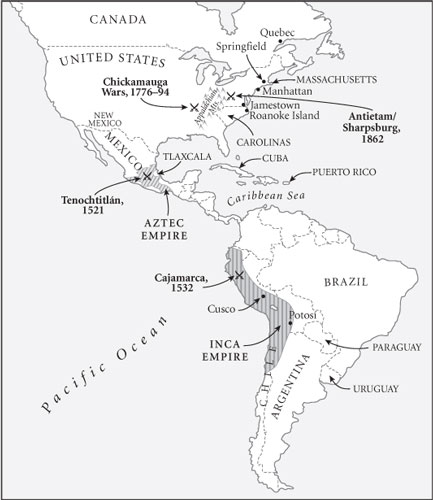

America, where the balance massively favored Europeans, saw the most extreme outcome. Distance and demography certainly worked against the interlopers, limiting the number of Europeans who could reach the New World to a tiny proportion of the number of Native Americans. But once Europeans arrived, the natives' stone blades, clubs, and cotton armor proved almost useless against steel swords, horses, and guns. Forty years after Columbus came ashore, a mere 168 Spaniards routed tens of thousands of Incas and captured King Atahuallpa at Cajamarca (

Figure 4.7

). Bulletriddled skulls from sixteenth-century cemeteries testify vividly to firepower's triumph over distance and demography.

Figure 4.7. Sites in the Americas mentioned in this chapter

Like the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean, however, Spaniards in the Americas learned that firepower was not always enough. In 1520, Cortés's conquistadors only escaped an Aztec uprising by the skin of their teeth, and their sack of Tenochtitlán the next year had as much to do with diplomacy as with guns. Cortés certainly had diplomatic problems of his own, at one point having to fight a civil war against a rival conquistador, but these paled next to the divisions among Native Americans. In Mesoamerica, the Tlaxcalans and other victims of Aztec imperialism were all too happy to revolt, while in Peru, Pizarro faced an Inca Empire that was bitterly divided after a recent civil war. The bulk of the troops that took Tenochtitlán and Cusco were in fact natives.

The biggest factor in the Spaniards' success, however, was disease. For thousands of years, European and Asian farmers had been living alongside domesticated animals and evolving the unpleasant suite of microbes described in

Chapter 3

. Native Americans, who had very few domesticated

animals, had no resistance to these infections. They had a few horrible ailments of their own (including syphilis) to give back to the Spaniards, but the exchange of infections worked overwhelmingly in Europe's favor.

“Sores erupted on our faces, our breasts, our bellies,” Aztec eyewitnesses said. “The sick were so utterly helpless that they could only lie on their beds ⦠They could not get up to search for food, and everyone else was too sick to care for them, so they starved to death in their beds.” Exact numbers

are disputed, but a recent DNA study shows that the Native population shrank by at least half across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.