War: What is it good for? (9 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Stoicism and Christianity assured the empire's subjects that unauthorized violence was wicked, which was good news for Leviathan, and the empire then vigorously exported these intellectual systems to its neighbors. Yet for all the contagiousness of the new ideas, they did not by themselves persuade anyone to join the empire. Only war or the fear of war could do that. Soft power worked its magic later, binding the conquered together and giving the empire a degree of unity.

As so often, it is the apparent exceptions to the war-first principle that prove the rule. The little city-states of ancient Greece, for example, had lots of reasons to forget their differences and come together in a larger community. Within each city, Greeks generally pacified themselves very well: by 500

B.C.

, men no longer went about their daily business armed, and around 430 one upper-class Athenian even complained that he could no longer go around punching slaves on the street (it was, in fact, illegal). When cities were at peace, their rates of violent death must have been among the lowest in the ancient world. Most, though, went to war roughly two years in every three. According to Plato, “What most men call âpeace' is just a fiction, and in reality every city is fighting an undeclared war against every other.”

No surprise, then, that dozens of squabbling Greek city-states agreed to surrender much of their sovereignty to Athens in 477

B.C.

But they did not choose this course out of love of peace or even admiration for Athens; they did it because they were frightened that the Persian Empire, which had tried to conquer Greece in 480, would gobble them up if they stood alone. And when, in the 440s, the Persian tide receded, several of the cities

thought better of their submission to Athens and decided to go it aloneâonly for the Athenians to use force to prevent them.

In the third and second centuries

B.C.

, a new wave of city-state amalgamations swept Greece. This time, groups of cities bundled themselves into

koina

(literally “communities,” but usually translated as “federal leagues”), setting up representative governments and merging their arrangements for security and finance. Once again, though, their prime motive was fear of wars they could not win by themselvesâinitially against the mighty Macedonian successors of Alexander the Great and then against the encroaching Romans.

The most peculiar stories may be those of Ptolemy VIII (nicknamed Fatso) and Attalus III, kings of Egypt and Pergamum, respectively. Ptolemy had been kicked out of Egypt by his brother (also named Ptolemy) in 163

B.C.

, and in 155

B.C.

the dispossessed Ptolemy drew up a will leaving his new kingdom of Cyrene to the Roman people if he died without heirs. Attalus, though, went further; he actually did die without heirs in 133

B.C.

, whereupon his subjects discoveredâto their astonishmentâthat they too had been bequeathed to the Roman Empire.

We do not know how the Romans felt about Ptolemy's will, since the overweight monarch in fact lasted another four decades and, after seducing his own stepdaughter, left rather a lot of heirs. We do know, though, that the Romans were as surprised as the Pergamenes by Attalus's bequest, and with self-interest strongly to the fore, competing factions in the senate fell into heated arguments over whether Attalus actually had the right to give his city to them.

Ptolemy and Attalus did what they did not because they loved Rome but because they feared it less than they feared war.

3

Lacking heirs, both men dreaded civil war. The brothers Ptolemy had already tried fratricide and gone to war even before Fatso drew up his will, and Attalus's position was worse still. A pretender to the throne, claiming to be Attalus's half brother, was stirring up revolt among the poor (and might have begun a civil war even before Attalus died), and four neighboring kings were waiting in

the wings to dismember Pergamum. No wonder a bloodless Roman takeover looked good to both kings.

This was the classical world's answer to Rodney King: No, we can't all get along. The only force strong enough to persuade people to give up the right to kill and impoverish each other was violenceâor the fear that violence was imminent.

To understand why that was so, though, we must turn to another part of the world entirely.

The Beast

In a jungle clearing on a South Sea island, a boy named Simon is arguing with a dead pig's head on a stick.

“Fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill!” says the head.

Simon does not reply. His tongue is swollen with thirst. A pulse is beating in his skull. One of his fits is coming on.

Down on the beach, his chums are dancing and singing. When these schoolboys first found themselves marooned on the island, all was fun and games: they swam, blew on conch shells, and slept under the stars. But almost imperceptibly, their little society unraveled. A shadow crept across their fellowship, haunting the forest like an evil beast.

Until today, that is. Today, a troop of teenage hunters impaled a screaming sow as she nursed her young. Whooping with excitement, the boys smeared each other with blood and planned a feast. But first, their leader recognized, there was something they had to do. He hacked the grinning head off the carcass and skewered it on the sharpened stick that they had used to kill the pig. “This head is for the beast,” he shouted into the forest. “It's a gift.”

And with that, the boys all set off running, dragging the flesh toward the beachâall except Simon, who crouches alone in the dappled, unreal light of the clearing.

“You knew, didn't you?” asks the pig's head. “I'm part of you? Close, close, close! I'm the reason why it's no go? Why things are what they are?”

Simon knows. His body arches and stiffens; the seizure is upon him. He falls, forward, forward, toward the pig's expanding mouth. Blood is darkening between the teeth, buzzing with flies, and there is blackness within, a blackness that spreads. Simon knows: the Beast cannot be killed. The Beast is us.

So says William Golding in his unforgettable novel

Lord of the Flies

. Cast away in the Pacific, far from schools and rules, a few dozen boys learn the dark truth: humans are compulsive killers, our psyches hardwired for violence. The Beast is us, and only a fragile crust of civilization keeps it in check. Given the slightest chance, the Beast will break loose. That, Golding tells us, is the reason why it's no go. Why Calgacus and Agricola fought, not talked.

Or is it? Another South Sea island, perhaps not so far from Golding's, seems to tell a different story. Like the novelist Golding, the young would-be anthropologist Margaret Mead suspected that in this simpler setting, where balmy breezes blew and palm fronds kissed the waves, she would see the crooked timber of humanity stripped of its veneer of civilization. But unlike Golding, who never actually visited the Pacific (although he was about to be posted there in charge of a landing craft when World War II ended), she decamped from New York City to Samoa in 1925 (

Figure 1.6

).

Figure 1.6. Lands of beasts and noble savages: locations outside the Roman Empire discussed in this chapter

“As the dawn begins to fall,” Mead wrote in her anthropological classic

Coming of Age in Samoa,

“lovers slip home from trysts beneath the palm trees or in the shadow of beached canoes, that the light may find each sleeper in his appointed place.”

Pigs' heads hold no terrors on Samoa. “As the sun rises higher in the sky, the shadows deepen under thatched roofs ⦠Families who will cook today are hard at work; the taro, yams and bananas have already been brought

from inland; the children are scuttling back and forth, fetching sea water, or leaves to stuff the pig.” The families gather in the evening to share their feast in peace and contentment. “Sometimes sleep will not descend upon the village until long past midnight; then at last there is only the mellow thunder of the reef and the whisper of lovers, as the village rests till dawn â¦

“Samoa,” Mead concluded, “is a place where no one plays for very high stakes, no one pays very heavy prices, no one suffers for his convictions or fights to the death for special ends.” On Samoa, the Beast is not close at all.

Golding and Mead both saw violence as a sickness, but they disagreed on its diagnosis. As Golding saw things, violence was a genetic condition, inherited from our forebears. Civilization was the only medication, but even civilization could only suppress the symptoms, not cure the disease. Mead drew the opposite conclusion. For her, the South Seas showed that violence was just a contagion, and civilization was its source, not its cure. Calgacus and Agricola fought two thousand years ago because their warlike cultures made them do it, and people carried on fighting in the twentieth century because warlike cultures were still making them do it.

In 1940, as France fell to Hitler, bombs rained down on London, and trenches filled up with murdered Polish Jews, Mead found a new metaphor. “Warfare,” she argued, “is just an invention.” Certainly, she conceded, war is “an invention known to the majority of human societies,” but even so, “if we despair over the way in which war seems such an ingrained habit of most of the human race, we can take comfort from the fact that a poor invention will usually give place to a better invention.”

Mead was not the only champion of this view, but she rapidly became the most influential. By 1969, when she retired from her position at the American Museum of Natural History, she was the most famous social scientist in the world and had proved, to the satisfaction of millions of readers, that humans' natural state was one of peace. Swayed by the consensus, anthropologist after anthropologist came back from the field reporting that their people were peaceful too (anthropologists have a habit of calling the group among whom they do fieldwork “my people”). This was the age of “War,” love-ins, and peace protesters promising to levitate the Pentagon; it was only to be expected that Rousseau would seem at long last to have won his bitter, centuries-old debate with Hobbes.

This was what Napoleon Chagnon thought, at any rate, when he swapped graduate school in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for the rain-forest borderlands

of Brazil and Venezuela in 1964. He fully expected the Yanomami people,

4

whose marriage patterns he planned to study, to live up to what he called “the image of âprimitive man' that I had conjured up in my mind before doing fieldwork, a kind of âRousseauian' view.” But the Yanomami had other ideas.

“The excitement of meeting my first Yanomamö was almost unbearable as I duck-waddled through the low passage [in the defensive perimeter] into the village clearing,” Chagnon wrote. Slimy with sweat, his hands and face swollen from bug bites, Chagnon

looked up and gasped when I saw a dozen burly, naked, sweaty, hideous men staring at us down the shafts of their drawn arrows! ⦠[S]trands of dark-green slime dripped or hung from their nostrilsâstrands so long that they clung to their pectoral muscles or drizzled down their chins. We arrived at the village while the men were blowing a hallucinogenic drug up their noses ⦠My next discovery was that there were a dozen or so vicious, underfed dogs snapping at my legs, circling me as if I were to be their next meal. I just stood there holding my notebook, helpless and pathetic. Then the stench of the decaying vegetation and filth hit me and I almost got sick â¦

We had arrived just after a serious fight. Seven women had been abducted the day before by a neighboring group, and the local men and their guests had just that morning recovered five of them in a brutal club fight ⦠I am not ashamed to admit that had there been a diplomatic way out, I would have ended my fieldwork then and there.

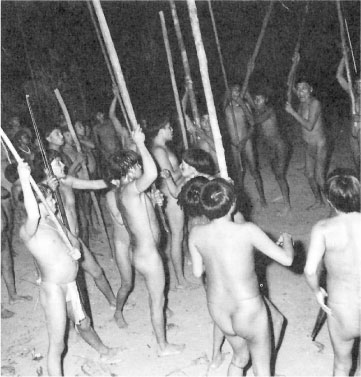

But he stayed and in more than twenty-five visits over the next thirty years learned that Yanomamiland was not Margaret Mead's Samoa. He witnessed, he said, “a good many incidents that expressed individual vindictiveness on the one hand and collective bellicosity on the other ⦠from the ordinary incidents of wife beating and chest pounding to dueling

5

and organized

raids ⦠with the intention of ambushing and killing men from enemy villages” (

Figure 1.7

).

Figure 1.7. Not the noble savage: A Yanomami club fight over a woman, photographed in the early 1970s. The dark line down the chest and stomach of the man at center-left is blood from his head.