Warning (24 page)

Authors: Sophie Cunningham

A lot of relationships that were shaky broke up and things like that. It was a time

for people to reassess everything. I sort of had a change of life, too, I suppose.

I had a change of female companions. The companion I was with went off with a 21-year-old

gambler, funny things like that, you know. It wasn't quite so funny at the time,

but it's quite humorous now.

6

Here's a waltz through police log books

7

at the time which give you a bit of an idea

of what life on the

Patris

was like: a person âdischarged' a firearm on 28 February

causing Constable Snoad to fire a shot. Snoad âwas relieved from duties' and a man

was arrested for disorderly behaviour. On Saturday 1 March police had to contact

a Bob Gillings to let him know his wife was dangerously ill in Brisbane. Later that

day Gillings was reported as drunk and disorderly in the public lounge of the

Patris

and police had to escort him to his cabin. On 3 March they tried to locate a man

(in fact a headmaster) who was living on the ship regarding a five-year-old missing

child who was believed to be camped in his car. On 5 March police boarded to look

for a missing girl, Elly Jones, who was fifteen and was believed to be with her friend

Maria in room 623. âNegative result.' On 8 March a message had to be given to Mr

R. G. Pollen regarding the death of his daughter-in-law. He couldn't be found. That

same day a person was asked to remove their motorcycle from a restricted area but

they refused. On 9 March an anonymous tip-off told police there was a game of two-up

on âMediterranean' deck. âIt appears very likely that a game had been in progress

but no evidence of same on arrival of police.' That same day there was also an incident

in which two police were assaulted, âoutnumbered and withdrew'. They returned with

more police and arrested two of the offenders. Complaints about noise in the lounge

were made later that night. On Saturday 15 March two drunken men accused each other

of assault and someone claimed that the

Patris

staff insulted them. On Sunday 16

March, several card games were reported. On 19 March an ambulance was called because

a woman was ill. On Sunday 23 March police:

received a complaint from a Mr Daltry of cabin no. 335 and a Mr Burns of cabin no.

298. Both men state they are disgusted with the behaviour in general on board the

ship. They said they had their wives and children on board and that they could not

use the lounge areas because of language, drinking and fighting. They further stated

they were going to see their Member of Parliament.

An arrest was made at 9.20 pm that night. The captain, Kandinis, reported trouble

on the gangway. Two men were ordered to be off the ship by noon the next day. On

24 March jewellery was nicked. On 27 March police had to look for the mother of a

baby that was in hospital. She wasn't found. The search for Elly Jones continued

and police were told that she might be found at the house of a man called Ralph.

She was later located at a shopping centre and returned to her mother. That day a

âdeath message' also had to be delivered, in which a man was told his father had

died. On 29 March there were reports of indecent assault. Police attended and spoke

to a woman âWho stated unknown personâ¦caught hold of the lower half of her two-piece

swimmers and pulled them down over her bottom, she stopped the person and left to

seek help.' The man was later located and âclaimed he had had a few beers and it

was only done as a joke.' The woman accepted the apology and didn't press charges

then changed her mind soon after saying âshe had been made a laughing stock of the

ship'. On the same night another man reported that two men had attempted to enter

his daughter's cabin and wouldn't leave. The girl's mother tried to get them to leave

and they still wouldn't go and only left once the father arrived. âPersons believed

to be members of visiting football teams. Unable to locate.' On 9 April a man became

upset about the noise outside his cabin and confronted three Greek teenage girls.

He âobtained no satisfaction'. The brother of one of the girls approached the man,

who punched him in the jaw. No charges were laid. In what is, perhaps, my favourite

entry, a complaint was received on 16 April âfrom a hippy type “gentleman” that Greeks

fishing off wharf had their radio cassette up too loudâ¦advised him that it would

be better to retire to his cabin where he wouldn't be able to hear the noise'.

At this point the suicide attempts began. On 15 April a man took an overdose of tabletsâThiorodazineâand

an ambulance had to be called. His girlfriend confirmed that he was depressed âand

they had been having domestic problems'. On 24 April there were reports that a woman

had overdosed or was about to. Her main complaint was that her children couldn't

sleep at night because of the noise aboard the ship. She was threatening to kill

herself with a mixture of Valium, sleeping pills and Diagesics. When her husband

was contacted he told them she'd had a breakdown. On 29 April another possible overdose

was reportedâthis time it was a young woman.

On 26 April a woman who was four months pregnant collapsed on the dance floor. On

27 April a statement was given regarding a man who was drunk and disorderly, describing

the man as âpissed⦠Abusive and aggressiveâ¦He hates coppers. I don't blame the police

for locking him up. He was in the wrong.' On 8 May a woman reported a man in her

cabin âwho has her key'. On 9 June a man was spoken to about âhitting and intimidating'

an eight-year-old boy who was not his son. On Monday 9 June there was a disturbance

when a man who was estranged from his wife became jealous of her alleged boyfriend.

He also thought his daughter was having a sexual relationship with a crew member.

And on it goes, relentlessly, until the

Patris

left Darwin Harbour on 14 November

1975.

Thirteen of those on the

Patris

were refugees from East Timor, which was in the throes

of the civil war that preceded the Indonesian invasion. Eric Rolls has described

the following scene. After the invasion itself, in early December 1975:

hundreds of frightened women and children got to Darwin in the clothes they stood

up in, by whatever ships they could catchâ¦The women, carrying babies and paper bags,

came ashore to the shouts of wharfies telling them to go home. The atmosphere in

Darwin was harsh; it was rebuildingâ¦

8

This contradicts many people's view that Darwin was, and continues to be, very passionate

about the East Timorese cause and that many Darwinites were extremely welcoming.

Either way, the Timorese had left a nation in ruins, to find a town not doing much

better.

Recovery is a complex process and it takes a long time. The nature of the disaster

will change communities forever: members are lost, services are disrupted, landscapes

are changed, people's sense of safety is compromised. Even resilient communities

can falter if the recovery period takes years. What happens to people is something

akin to war weariness, a condition people in other circumstances have nicknamed âbushfire

brain'. Chemically speaking it's been described as the moment when people run âout

of adrenaline' and move âinto cortisole'.

9

This is one of the reasons it's said that

the third year after a disaster is often the hardest. This is the case whether you've

stayed in the place where disaster struck or whether you've attempted to get on with

your life elsewhere.

But three years? Even getting that far looked like a long haul at the end of 1975.

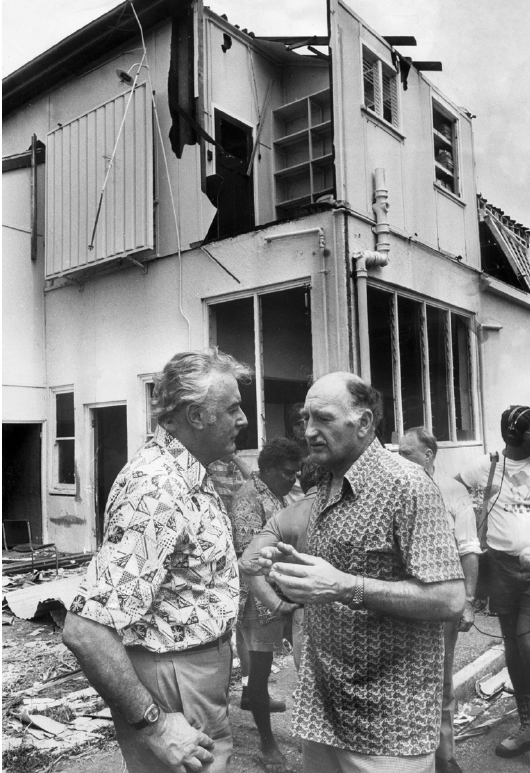

The PM and the major-general:

Whitlam and Stretton in conversation

JOHN HART / FAIRFAX

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam is

taken on a tour of the wreckage

NEWS LTD / NEWSPIX

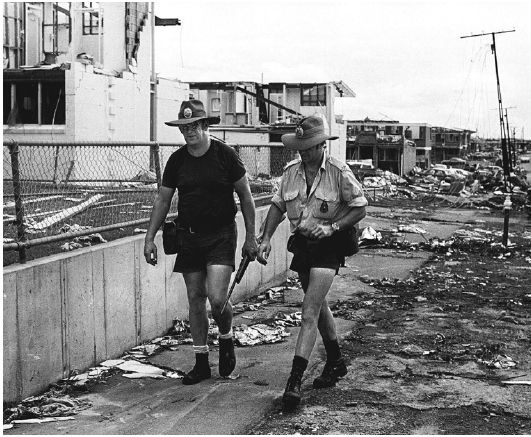

Police, armed against stray dogs, check houses in the Casuarina area

RICK STEVENS / FAIRFAX

Dead horse in a trailer being taken out of town along McMillans Road

NORTHERN TERRITORY ARCHIVES SERVICE, BARBARA JAMES, NTRS 1683

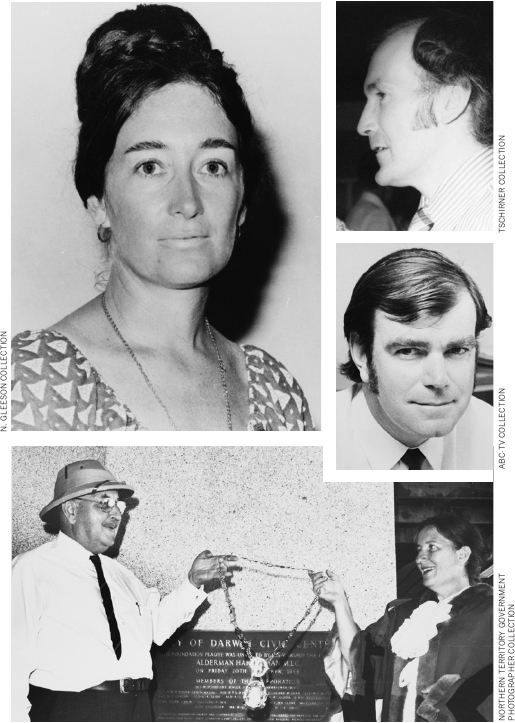

Clockwise from top left: Dawn Lawrie, 1977;

Hedley Beare (date unknown); Ray McHenry (date unknown);

Tiger Brennan shares the mayoral regalia with Ella Stack, 1975

ALL PHOTOS THIS PAGE FROM THE NORTHERN TERRITORY LIBRARY

I WASN'T WORRYING ABOUT BLOODY HISTORY.

I WAS WORRYING ABOUT THE DAY

MONEY, AFTER those cashless days and weeks following Tracy, was beginning to dominate

people's lives again: who got it, who deserved it, how it was spent.

In an address to the Melbourne Press Club on 9 November 1976, Major-General Stretton

waxed sentimental for a moment: âFor a few glorious days the nation came together.

We became one country with one purpose. If only we could recapture that unity, keep

that spirit of Darwin going at all times.' Then he went on to express his concern

about the ways in which millions of dollars in relief funds were being spent and

call for a Royal Commission into the Cyclone Tracy Relief Trust Fund. âI do not question

the honesty of the trustees. However I do question the priorities.' Stretton felt

that money should be spent on people, not on rebuilding churches, schools, cultural

centres and the like. His point was that almost half of those evacuated never returned,

âSo the cultural centre is not going to do them much good, is it?'

These days rebuilding such infrastructure would be seen as unequivocally essential

to rebuilding a community after a disaster. But Stretton was not alone in his view

and Ray McHenry expressed similar concerns about the uses the funds were put to.

It's no surprise. These questions arise again and again after all disasters: the

misallocation of funding, changes in land use that favour the rich, and the politics

of exclusion of the poor and ordinary people from policy-making and decision-making.

The Cyclone Tracy Relief Trust Fund had been established at the beginning of 1975,

when the federal cabinet decided that donations and offers of overseas assistance

from the South Pacific, Europe and Africa needed to be formalised. As well, there

were nationwide appeals encouraging Australians to donate money and goods. Minister

Rex Patterson was the chairman of the fund, and its members included Jock Nelson,

Mayor Tiger Brennan, Paul Everingham, Ella Stack and Alec Fong Lim. They received

and distributed more than eight million dollars before being formally wound up in

October 1976. As well as paying for various aspects of the rebuild, the fund gave

out benefits that were allotted with blunt directness: women who had lost their husbands

got a payout of ten thousand dollars, whereas a lost wife was only worth five thousand.

Regardless of the crassness of this kind of assessment, money was obviously extremely

important at this time. While Les Garton remembers that some people tried to rip

off the insurance companies after Tracy, in the great scheme of things this was not

nearly as big a problem for the community as the opposite situation: people being

woefully underinsured or not insured at all. In early 1975 the Department of Repatriation

and Compensation surveyed 10,419 persons and 1830 businesses to try to assess damage.

It was estimated that losses amounted to 187 million dollars, and of this amount

89 million was uninsured. Julia Church remembers that her parents weren't insured

and the ramifications of that were enormous for themâas they were for many older

people. Jim Bowditch, who was in his fifties, lost everything. Ken Frey, who had

been about to retire, is just one of thousands who acknowledges âfinancially of course,

it was a bit of a disaster'. He, like many others who'd survived the cyclone, would

struggle to get another mortgage. Certainly the costâfinancial, emotional and physicalâwas

simply too much for some people.

The reasons people weren't properly insured were various: lack of money, lack of

care, lack of organisation, and a general reluctance to accept that a disaster might

affect them directly. Not much has changed on that front. After Black Saturday insurance

claims totalled more than a billion dollars but it was estimated that as many as

thirteen per cent of the residential properties destroyed were not insured at all.

And of course, as insurance premiums go up in response to the increasing number

of disasters, it's likely that the percentage of people that remain uninsured will

increase. Certainly the magnitude of claims that arose from the Brisbane floods in

early '74 followed by Tracy at the end of that year led some insurance companies

to âwithdraw from high-risk areas'. The insurance payout for Tracy was, at the time,

the largest in Australian history at 200 million AUD (equivalent to 1.25 billion

dollars today). Following Cyclone Tracy, the Insurance Council of Australia established

the Insurance Emergency Service which developed into today's Insurance Disaster Response

Organisation. More than fifty per cent of weather-related insurance payments in

the last thirty years have been for tropical cyclone damage.

1

On 31 May the federal government passed the

Darwin Cyclone Damage Compensation Act

1975

which was designed to compensate people for loss and damage on property up to

fifty per cent of its value at the time of the cyclone, with an upper limit of twenty-five

thousand dollars for houses and business premises and five thousand for personal

belongings. Claims had to be lodged by 30 September 1975. More than twelve thousand

household claims and almost six hundred business claims were processed. Just under

twenty-six million dollars was paid in compensation and most claims were settled

by June 1976.

The length of time it takes insurers to settle, or for compensation to come through,

is always contentious. Two years after the series of earthquakes in Christchurch,

most notably the big one of 22 February 2011, commentators were describing the insurance

problems people were facing as âa second earthquake'. Ninety per cent of people affected

by the earthquake had made claims but two years later a massive sixty-nine per cent

of them were waiting for a resolution. Some simply gave up and moved on, with no

idea of whether they would ever receive any compensation.

On 31 December 1974 the federal government set up an interim Darwin Reconstruction

Commission (DRC). According to the

NT News

, âThe commission will be asked to decide

on the best use of Darwin's lands and remaining buildings. It will also be called

on to make recommendations about the type of building that should go up in place

of those torn down by Cyclone Tracy.' People assumed the worst when they read this,

and by 3 January there were rumours that the Northern Territory's administrative

capital was to be moved to Alice Springs. Such paranoia wasn't totally unreasonableâthere

were

conversations taking place questioning whether Darwin should be rebuilt at all.

Similar debate flares up after many a natural disaster. But as Dr Greg Holland, a

meteorologist, a survivor of Cyclone Tracy and now an atmospheric scientist in the

US, said on

Lateline

soon after the Black Saturday bushfires: âLet's be honest: it's

very hard to build in any area that's not dangerous to some extent.'

2

It is certainly

unrealistic to expect that we won't build in areas where extreme weather occurs,

in part because the population is growing exponentially, and in part because there

is more extreme weather occurring all over the planet. More people live on flood

plains and in surge zones, more people live in caravan parks in Tornado Alley, more

people live in semi-rural areas bound to be affected by bushfire.

The DRC proper got going on 28 February 1975 when the

Darwin Reconstruction Act

was

passed. It comprised eight members: Anthony Powell (chairman), Alan O'Brien (deputy

chairman), Goff Letts, Ella Stack, Carl Allridge, Alan Reiher, P. L. Till and Martyn

Finge. Their brief was to plan, coordinate and undertake the rebuild, with the CSIRO

being called upon to advise new standards. Between 1975 and 1978 the DRC coordinated

many construction projects including the building or repair of more than 2500 homes.

First up, though, they worked with the Cities Commission, a small Commonwealth agency

established in 1973, to produce a town plan. There were many who felt, like Harry

Giese, that the Cities Commission had made a mess of Canberra and now they planned

to make a mess of Darwin. And it's true that when the DRC was established Darwin

was compared to âCanberra, Albury/Wodonga and other areas selected by the Whitlam

government for “regional growth”.'

3

Ten years later Suzanne Spunner would write that

she âwas not prepared for the northern suburbs, flattened by the cyclone and rebuilt

with miles and miles of kerbing, landscaped in wider and wider circles, courts, crescents

and cul-de-sacs. Canberra with palms.' There was a strong feeling that people couldn't

just come in from the outside, without understanding the psyche of Darwin, and tell

them how to live. And there are clear echoes between Darwin residents' objections

to having their land and autonomy taken from them, and the objections made by the

area's original inhabitants, the Larrakia, to the same process.

Not long after the cyclone Jack Meaney was on his way to the council offices to see

what needed doing (he ended up working as a cook at an evacuation centre), when he

bumped into Bishop O'Loughlin. At the time Meaney was bemused by O'Loughlin's distress

about Christ Church, which had been destroyed within an hour of midnight mass. The

church had been built in 1917 and, âHe was really concerned about that old building,

being a part of the history I suppose. I wasn't worrying about bloody history. I

was worrying about the day.'

This fairly succinctly sums up the tensions in Darwin during the months and years

of the rebuild. The cyclone made some residents more mindful of the importance of

the city's heritage, while others just wanted to get their lives back on track as

quickly as possible. So which side were those responsible for the rebuild on? Moving

forward as quickly as possible, or hanging on to the bits of Darwin's history that

could be salvaged from the wreckage? More contentiously still, should the rebuild

take into account the possibility of future environmental traumas: more cyclones,

higher storm surges?

Neville Barwick, who led the Darwin Reconstruction Study Group, arrived in town a

few days after the cyclone and, among other work, began his survey of historical

ruins with a view to assessing whether they could be saved. This was important work.

But Meaney was right that in the immediate aftermath of Tracy, just surviving was

as much as most people were up for.

At this time, when Darwin was often described as a giant rubbish tip, the fact there

was no recycling of building materials became a cause of contention. Ken Frey remembers

that so much timber was going to the tip he was worried there would be a termite

problem, but he also believed it wasn't realistic to reuse the material under those

conditionsâit was too hard for the front-end loaders to clear the wreckage if you

were also trying to sort as you went. Government architect Cedric Patterson concurs.

âThere was a lot of good materials dumped but where do you stop?' The desire to do

things quickly became, as so often before, the decisive factor. The Indigenous publication

Bunji

stated: âThe settlers are rushing about like ants, rebuilding. They are filling

our land with their rotting garbage.'

Hip Strider's heart was broken by the authorities' refusal to recycle debris as building

material. All these âyou-beaut building materials that would have been perfectly

satisfactory to house the population were taken down to the dump'.

4

Bernard Briec

and his family, who had planned to stay in Adelaide after their evacuation, missed

Darwin so much they were back there by April. He remembers hanging out at Lee Point

dump, which became a favourite scavenging spotâso at least the old building materials

got to be reused by some.

The day Ella Stack was elected, the

Sydney Morning Herald

ran the story under the

headline: âAfter TracyâElla gets a louder voice'. Her first task after her election,

she told the paper, âwould be to read up on the thousands of words that had been

handled by the Darwin Reconstruction Commission'.

5

She was referring to the DRC's

first report, which was delivered mid-year. That report recommended a balance between

those who wanted the town rebuilt exactly as it had been, and those who wanted a

thorough redesign. Some of the recommendations made real senseâanyone who has spent

time in Darwin and experienced the way the airport carves the town in half would

understand suggestions to resituate it. The airport was just one matter on which

the city was recalcitrant.

Overall, the response to the report was extremely negative. It was felt that planners

overlooked people's emotional investment in their own blocks of land.

6

For example,

the entire suburb of Coconut Grove and some of Fannie Bay were to become parklands.

That was obviously difficult for residents of those suburbs to take. Some 1200 objections

were made to this first plan.

Discussions about whether rebuilding could take place within surge zonesâand how

those zones should be designatedâbecame particularly fraught. Storm surges move from

two to five metres above a normal tide and are often what kill people after a cyclone.

It was the surge after Hurricane Katrina that caused such catastrophic damage, and

that killed most of the eight thousand who died in Galveston in 1900.

The DRC wanted to play it safe and plan for a worst-case scenario but there wasn't

much patience for long-term planning, particularly since the surge hadn't been a

real problem after Tracy. Cedric Patterson, always the pragmatist, pointed out that

if you took surge zones seriously âit practically wipes out about a quarter of Darwin'.

And, as is often the case, the surge zone included some of Darwin's finest real estateâincluding

Mayor Ella Stack's house. Stack spoke for many Darwinites when she argued the surge

line had not been high for some hundred years. Brave planners argued that there was

no way of knowing what was to come. But when they eventually backed off it infuriated

people even more. Spike Jones, a technician with the PMG who'd lived in Darwin for

some twenty-four years, complained, âAll that stuff about buffer zones and green

belts and the surge line, then they back off anyway. What a waste of time!'

7