Watson, Ian - SSC

Authors: The Very Slow Time Machine (v1.1)

The Very Slow Time Machine

IAN WATSON

“Perhaps

the most purely brilliant of the new SF writers of the Seventies

. .

-Fantasy & Science Fiction

“One

of the few around who is not afraid to use the new sciences of communication as

well as the old ones of technology

. .

—The

London

Times

“The

most interesting British sf writer of ideas ... he writes a heady, zest-filled

prose that whips up a froth of speculation .

. ”

—J.G.

Ballard

THIS YEAR’S WINNER OF

THE BRITISH SCIENCE FICTION

ASSOCIATION’S AWARD

Here is a collection of his most exciting

stories, stories bound to take you to the outer edges of reality . . . and

beyond.

THE EMBEDDING

THE JONAH KIT

THE MARTIAN INCA

ALIEN EMBASSY

MIRACLE VISITORS

THE VERY SLOW

TIME MACHINE

BY IAN WATSON

ace

books

A Division of Charter Communications Inc.

A GROSSET & DUNLAP COMPANY

360 Park Avenue

South

New York

,

New York

10010

Copyright

© 1979 by Ian Watson

All rights reserved. No part of this book

may be reproduced in any form or by any means, except for the inclusion of

brief quotations in a review, without permission in writing from the

publisher.

All characters in this book are fictitious.

Any resemblance to actual persons, living or

dead,

is

purely coincidental.

An ACE Book

by

arrangement with Victor Gollancz Ltd.

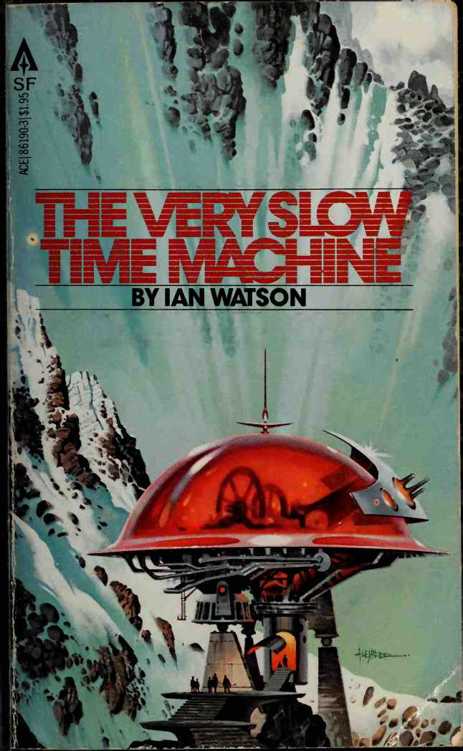

Cover art by Paul Alexander

First Ace printing: April 1979

Printed in

U.S.A.

The Very Slow Time

Machine

first appeared in Anticipations edited by Christopher

Priest, 1978.

Thy

Blood

Like

Milk

first appeared in

New

Worlds

Quarterly,

1973.

Sitting on

a Starwood Stool

first appeared in Science Fiction

Monthly

,

1974.

Agoraphobia,

A.D.

2000

first appeared in Andromeda

2 edited by Peter Weston, 1977.

Programmed

Love Story first appeared in Transatlantic Review, 1974.

The

Girl Who Was Art first appeared in Ambit, 1976.

Our

Loves So Truly Meridional first appeared in Science Fiction

Monthly

,

1974.

Immune Dreams first appeared in

Pulsar

1 edited by George Hay, 1978.

My Soul Swims in

a Goldfish Bowl

first appeared in

The Magazine of Fantasy &

Science

Fiction,

1978.

The Roentgen Refugees first appeared in

New

Writings in SF 30 edited by Ken

Bulmer, 1978.

A

Time-Span to

Conjure With first appeared in Andromeda 3 edited by

Peter Weston, 1978.

On

Cooking

the First Hero in

Spring

first appeared in Science

Fiction Monthly,

1975.

The

Event

Horizon first appeared in

Faster

Than Light:

an

original anthology about interstellar travel

edited by Jack Dann

and George Zebrowski, 1976.

The lines of verse in The

Event Horizon

(31 lines from “Diwan

over the Prince of Emgion” and 6 lines from “The Tale of Fatumeh”) are from

Selected

Poems by Gunnar Ekelof,

translated by W. H. Auden and Leif Sjoberg.

Copyright© Ingrid

Ekelof, 1965, 1966.

Translations copyright© W. H.

Auden and Leif Sjoberg, 1971.

Reprinted by permission of Penguin Books

Ltd.

For

Nell and Bill Watson

THE VERY SLOW TIME MACHINE

(1990)

The

Very Slow Time Machine—for convenience: the

VSTM[

1]—made

its first appearance at exactly

midday

1 December 1985

in an unoccupied space at the National

Physical Laboratory. It signalled its arrival with a loud bang and a squall of

expelled air. Dr. Kelvin, who happened to be looking in its direction,

reported that the VSTM did not exactly spring into existence instantly, but

rather expanded very rapidly from a point source, presumably explaining the

absence of a more devastating explosion as the VSTM jostled with the air

already present in the room. Later, Kelvin declared that what he had actually

seen was the implosion of the VSTM. Doors were sucked shut by the rush of air,

instead of bursting open, after all. However it was a most confused moment— and

the confusion persisted, since the occupant of the VSTM (who alone could shed

light on its nature) was not only time-reversed with regard to us, but also

quite crazy.

One

infuriating thing is that the occupant visibly grows saner and more

presentable (in his reversed way) the more that time passes. We feel that all

the hard work and thought devoted to the enigma of the VSTM is so much energy

poured down the entropy sink—because the answer is going to come from him, from

inside, not from us; so that we may as well just have bided our time until his

condition improved (or, from his point of view, began to degenerate). And in

the meantime his arrival distorted and perverted essential research at our

laboratory from its course without providing any tangible return for it.

The

VSTM was the size of a small station wagon; but it had the shape of a huge

lead sulphide, or galena, crystal—which is, in crystallographer’s jargon, an

octahedron-with-cube formation consisting of eight large hexagonal faces with

six smaller square faces filling in the gaps. It perched precariously—but

immovably—on the base square, the four lower hexagons bellying up and out

towards its waist where four more squares (oblique, vertically) connected with

the mirror- image upper hemisphere, rising to a square north pole. Indeed it

looked like a kind of world

globe,

j lopped and

sheered into flat planes: and has remained very much a separate, private world

to

1

this day, along with its passenger.

All

faces were blank metal except for one equatorial square facing

southwards

into the main body of the laboratory. This was a

window—of glass as thick as that of a deep-ocean diving bell—which could

apparently be opened from inside, and only from inside.

The passenger within looked as

ragged and tattered as a tramp; as crazy, dirty, woe-begone and tangle-haired

as any lunatic in an ancient Bedlam cell. He was apparently very old; or at any

rate long solitary confinement in that cell made him seem so. He was pallid,

crookbacked, skinny and rotten-toothed. He raved and mumbled soundlessly at

our spotlights. Or maybe he only mouthed his ravings and mumbles, since we

could hear nothing whatever through the thick glass. When we obtained the

services of a lip- reader two days later the mad old man seemed to be mouthing

mere garbage, a mishmash of sounds. Or was he? Obviously no one could be

expected to lip-read backwards; already, from his actions and gestures, Dr.

Yang had suggested that the man was time-reversed. So we video-taped the

passenger’s mouthings and played the tapes backwards for our lip-reader. Well,

it was still garbage. Backwards, or forwards, the unfortunate passenger had

visibly cracked up. Indeed, one proof of his insanity was that he should be

trying to talk to us at all at this late stage of his journey rather than

communicate by holding up written messages—as he has now begun to do. (But more

of these messages later; they only begin—or, from his point of view, cease as

he descends further into madness—in the summer of 1989.)

Abandoning

hope of enlightenment from him, we set out on the track of scientific

explanations.

(Fruitlessly.

Ruining

our other, more important work.

Overturning our

laboratory projects—and the whole of physics in the process.)

To

indicate the way in which we wasted our time, I might record that the first

“clue” came from the shape of the VSTM which, as I said, was that of a lead

sulphide or galena crystal. Yang emphasized that galena is used as a

semiconductor in crystal rectifiers: devices for transforming alternating

current into direct current. They set up a much higher resistance to an

electric current flowing in one direction than another. Was there an analogy

with the current of time? Could the geometry of the VSTM—or the geometry of

energies circulating in its metal walls, presumably interlaid with printed

circuits—effectively impede the forward flow of time, and reverse it? We had

no way to break into the VSTM. Attempts to cut into it proved quite ineffective

and were soon discontinued, while X-raying it was foiled, conceivably by lead

alloyed in the walls. Sonic scanning provided rough pictures of internal

shapes, but nothing as intricate as circuitry; so we had to rely on what we

could see of the outward shape, or through the window—and on pure theory.

Yang

also stressed that galena rectifiers operate in the same manner as diode

valves. Besides transforming the flow of an electric current they can also

demodulate.

They separate information

out from a modulated carrier wave—as in a radio or TV set. Were we witnessing,

in the VSTM, a machine for separating out “information”—in the form of the

physical vehicle itself, with its passenger—from a carrier wave stretching back

through time? Was the VSTM a solid, tangible analogy of a three-dimensional TV

picture, played backwards?

We

made many models of VSTMs based on these ideas and tried to send them off into

the past, or the future—or anywhere for that matter! They all stayed

monotonously present in the laboratory, stubbornly locked to our space and

time.

Kelvin,

recalling his impression that the VSTM had seemed to expand outward from a

point, remarked that this was how three-dimensional beings such as ourselves

might well perceive a four-dimensional object first impinging on us. Thus a 4-D

sphere would appear as a point and swell into a full sphere then contract again

to a point.

But a 4-D octahedron-and-cube?

According

to our maths this shape couldn’t have a regular analogue in 4-space, only a

simple octahedron could. Besides, what would be the use of a 4-D time machine

which shrank to a point at precisely the moment when the passenger needed to

mount it? No, the VSTM wasn’t a genuine four-dimensional body; though we

wasted many weeks running computer programs to describe it as one, and arguing

that its passenger was a normal 3-space man imprisoned within a 4-space

structure—the discrepancy of one dimension between him and his vehicle

effectively isolating him from the rest of the universe so that he could travel

hindwards.

That

he was indeed travelling hindwards was by now absolutely clear from his feeding

habits (i.e. he regurgitated), though his extreme furtiveness about bodily

functions coupled with his filthy condition meant that it took several months

before we were positive, on these grounds.

All

this, in turn, raised another unanswerable question: if the VSTM was indeed

travelling backwards through time, precisely where did it

disappear

to, in that instant of its arrival on

1

December 1985

? The

passenger was hardly on an archaeological jaunt, or he would have tried to

climb out.

At

long last, on

midsummer day

1989, our passenger held

up a notice printed on a big plastic eraser slate.

CRAWLING DOWNHILL, SLIDING UPHILL!

He held this up for ten minutes,

against the window. The printing was spidery and ragged; so was he.

This

could well have been his last lucid moment before the final descent into

madness, in despair at the pointlessness of trying to communicate with is.

Thereafter it would be

downhill all the

way,

we interpreted. Seeing us with all our still eager, still baffled

faces, he could only

gibber incoherently thenceforth like

an enraged monkey at our sheer stupidity.

He

didn't communicate for another three months.

When

he held up his next (i.e. penultimate) sign, he looked slightly sprucer, a little

less crazy (though only comparatively so, having regard to his final mumbling

squalor).

THE LONELINESS! BUT LEAVE ME ALONE!

IGNORE ME UNTIL 1995!

We held up signs (to which, we soon

realized, his sign was a response):

ARE YOU TRAVELLING BACK THROUGH TIME? HOW?

WHY?

We would have also dearly loved to

ask:

WHERE DO YOU DISAPPEAR TO ON

DECEMBER

1 1985

? But

we judged it unwise to ask this most pertinent of all questions in case his

disappearance was some sort of disaster, so that we would in effect be

foredooming him, accelerating his mental breakdown. Dr. Franklin insisted that

this was nonsense; he broke down anyway. Still, if we had held up that sign,

what remorse we would have felt: because we

might

have caused his breakdown and ruined some magnificent undertaking.

.

. . We were certain that it had to be a magnificent undertaking to involve

such personal sacrifice, such abnegation, such a cutting off of oneself from

the rest of the human race. This is about all we were certain of.

(1995)

No

progress with our enigma. All our research is dedicated to solving it, but we

keep this out of sight of him. While rotas of postgraduate students observe him

round the clock, our best brains get on with the real thinking elsewhere in the

building. He sits inside his vehicle, less dirty and dishevelled now, but

monumentally taciturn: a

trappist

monk under a vow of

silence. He spends most of his time re-reading the same dog-eared books, which

have fallen to pieces back in our past: Defoe’s

Journal of the Plague Year

and

Robinson

Crusoe

and Jules Verne’s

Journey to

the Centre of the Earth;

and listening to what is presumably taped

music—which he shreds from the cassettes back in 1989, flinging streamers

around his tiny living quarters in a brief mad fiesta (which of course we see

as a sudden frenzy of disentangling and repackaging, with maniacal speed and

neatness, of tapes which have lain around, trodden underfoot, for years).

Superficially

we have ignored him (and he, us) until 1995: assuming that his last sign had

some significance. Having got nowhere ourselves, we expect something from him

now.

Since

he is cleaner, tidier and saner now, in this year of 1995 (not to mention ten

years younger) we have a better idea of how old he actually is; thus some clue

as to when he might have started his journey.

He

must be in his late forties or early fifties— though he aged dreadfully in the

last ten years, looking more like seventy or eighty when he reached 1985.

Assuming that the future does not hold in store any longevity drugs (in which

case he might be a century old, or more!) he should have entered the VSTM

sometime between 2010 and 2025. The later date, putting him in his very early

twenties if not teens, does rather suggest a “suicide volunteer” who is merely

a passenger in the vehicle. The earlier date suggests a more mature researcher

who played a major role in the development of the VSTM and was only prepared to

test it on his own person. Certainly, now that his madness has abated into a

tight, meditative fixity of posture, accompanied by normal activities such as

reading, we incline to think of him as a man of moral stature rather than a

time-kamikaze; so we put the date of commencement of the journey around 2010 to

2015 (only fifteen to twenty years ahead) when he will be in his thirties.