We Two: Victoria and Albert (29 page)

Read We Two: Victoria and Albert Online

Authors: Gillian Gill

Victoria drew Albert’s picture. Albert corrected the mistakes in Victoria’s letters. Seated on a little blue sofa, Victoria nestled in Albert’s bosom, and, when he sat at the piano, she dropped kisses on his head as she passed. He responded eagerly, embracing her passionately, telling her over and over again how much he loved her, and covering her hand with kisses—how small it was in comparison with Ernest’s! He called her

Vortrefflichste

, most splendid of women. Savoring an intimacy that she had craved since childhood and that he had not expected to enjoy, they were deliriously happy. Never would they be quite so happy again.

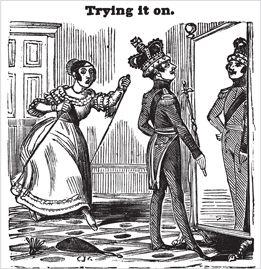

AS WORD OF THEIR

Queen’s impending marriage seeped out, Victoria’s subjects were titillated by the peculiar, one could say unique, problems facing

the royal couple. Who would wear the breeches, saucily demanded English commentators. Humor of this kind was supremely distasteful to Prince Albert, in no small measure because he was, in fact, obsessed by the very same question, framed more delicately. Who would have the upper hand in the marriage, he or Victoria?

For every other married couple in Great Britain, the answer was preordained and crystal clear, if not undisputed. The vast majority of both men and women in the nineteenth century agreed that by nature, religion, law, and immemorial custom men were superior to women. Biological science and social theory buttressed men’s claims to supremacy not only in politics, administration, and business, but also in the home. According to the legal doctrine of “feme covert,” a British woman who married lost all her independent legal and civil status. She and her husband were viewed by the law as one entity, and that entity was he. A married woman’s property, unless controlled by her natal family through a prenuptial agreement, was her husband’s. Anything she earned was legally his to do with as he willed. She could not buy or sell property or enter into any legal transaction without his leave.

A husband could legally enforce sexual congress on his terms. He could physically chastise his wife, sequester her in the home, or commit her to a madhouse without much fear of the law. The children of the marriage were, in effect, the property of the husband, and through his last will and testament he could dispose of them as he chose even after death. Divorce for a husband was possible, if unpleasant and expensive. For a wife it was prohibitively difficult. The message to a woman in mid-nineteenth-century Great Britain was clear: Like a child, a felon, or a madman, she had no role to play in the public sphere. In the marketplace she was at most a consumer. Her place was in the home. Her duty and her pleasure must be to obey her menfolk, and dedicate her life to her family.

But Victoria was not just a woman. She was a woman who reigned, a queen regnant, and this changed her relationship to every man and woman. The anomalousness of her situation was keenly apparent to her contemporaries at the time of her accession. As the radical politician Lord Brougham plaintively explained in an anonymous pamphlet: “An experienced man, well stricken in years, I hold myself before

you

, a girl of eighteen, who, in my own or any other family in Europe, would be treated as a child, ordered to do as was most agreeable or convenient to others—whose inclinations would never be consulted—whose opinion would never be thought of—whose consent would never be asked upon any one thing appertaining

to any other human being but yourself, beyond the choice of gown or cap, nor always upon that: yet before you I humble myself.”

When Victoria decided to marry, the anomaly of her legal and civil status became even more pronounced. In certain respects, she seemed the traditional bride. She was small and very feminine. She came to marriage as a guaranteed virgin, since she had been watched night and day since her birth. She was likely to bear children, since she was healthy, sexually mature, and came from a line of fertile women. All of this was eminently pleasing to the patriarch in Prince Albert. But as a social and legal entity, Victoria was far more man than woman.

As Queen of England, Victoria was at the apex of national power and international status. Far from being a purely domestic creature, sheltered from the world, she had an exceptionally busy and demanding full-time job, and her whole life was lived in the public eye. England was very rich, and Victoria occupied the top of the governmental pyramid. She had a huge salary and enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle at state expense. She was also wealthy in her own right.

None of this would change when the Queen married. Governed by the British constitution, not British civil law, Victoria was the only woman in Great Britain and Ireland to whom the law gave full, independent legal control over her income and possessions whether or not she was married. Most of what Victoria had she could not sell, bequeath, or otherwise alienate. For her lifetime she held what she had in trust for her successor in a unique kind of entail. Her chief source of income, her parliamentary allowance under the civil list, was hers by virtue of her position as head of state.

These were the facts of Victoria’s life. She knew them well, and, with some important provisos, they were very much to her taste. She took her duties and responsibilities as queen seriously, and enjoyed the work of monarchy. She was aware that she showed more talent for the job than most of her male predecessors. She reveled in her power and her independence.

Albert’s situation was very different. He was a very young man of great integrity and ability with very little experience of life outside the home and the classroom. He was a proud youth, confident of being the equal of any man and better than most. At the same time, he was conscious that most European princes were richer and more powerful than he. He was a misogynist, confident of being superior to all women without exception, who was yet obliged to make marriage his career. Victoria, Queen of England, was the most magnificent mate to whom he could possibly aspire. Becoming her

husband was, pun intended, his crowning achievement. What he brought to his marriage were the traditional gifts of a princess bride: beauty, pedigree, chastity, and the promise of royal children. Prince Albert was a man of reason who prided himself on his self-control and cool temperament. But the discrepancy between his self-image and the world’s opinion gnawed at the roots of his peace.

As Victoria and Albert spooned on the little blue sofa, each had a secret agenda. Victoria was determined to change as little as possible in her delightful life as queen. She intended to have her Albert and her own way. She would continue to see her ministers

alone!

She would remain independent by retaining control over her property, her 385,000 pounds from the civil list, and her private income.

Albert, for his part, was determined to institute the traditional balance of power between husband and wife by becoming the master in his wife’s house. He would manage her worldly goods even if he could not own them. Educated in statecraft by King Leopold and Baron Stockmar, Albert planned to take the reins of power from Victoria once they were married. He would leave her queen only in name.

BETWEEN OCTOBER 1839

, when Prince Albert arrived at Windsor Castle, and the wedding in February 1840, Victoria held all the trump cards. Like a princess in a fairy story, she imposed upon Albert a series of tests and ordeals. The prince had to beg through family intermediaries for an invitation

to come to England to see the Queen. When the invitation came, it was grudging and issued on the strict proviso that Her Majesty committed herself to nothing. After Victoria had looked Albert over and decided that, indeed, he was the husband she was looking for, her first impulse was not to clasp her beloved in her arms but to go into delicious conclave with her prime minister over how exactly she should propose and what arrangements would have to be made for the wedding.

Only then did Victoria summon Albert to her boudoir in her ancestral castle for a private interview. She proposed marriage, never doubting, for all her maidenly protestations, that he would accept. She magnanimously conducted the proposal interview in German, since she knew Albert was at a disadvantage in English. Victoria cooed her adoration and shed tears over the sacrifice Albert was making in marrying her, but the very structure of the proposal spoke volumes. Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, of her free choice, was condescending to marry a mere prince of Coburg because she found him agreeable. Very much the great lady, she was also very careful to save his feelings.

Now that she had made her decision, Victoria was eager to have Albert by her side. She set the marriage date for February 10, and on November 14, Albert left Windsor for Coburg, stopping for a few days en route at Wiesbaden, where his uncle and Baron Stockmar were both waiting for him. There, according to Stockmar’s memoirs, “All the circumstances and difficulties connected with Prince Albert’s position in England were submitted to a detailed and exhaustive discussion.” The Coburgs had no trust in the security of the regular mails, knowing government officials all over Europe routinely opened letters, so a special system of couriers was set up between London, Coburg, Wiesbaden, and Brussels. As soon as Albert left for Coburg, Stockmar traveled to London, charged with negotiating the marriage settlement.

One thing that was certainly part of the discussion between Albert, his uncle, and Baron Stockmar was Lord Melbourne and the prime minister’s relationship with the Queen. Stockmar and Leopold had known Melbourne, Palmerston, Wellington, and all the other key players on the English political stage for twenty years. They had grown old with them. While Melbourne was enduring the Byron scandal and Palmerston (reportedly) was bedding three of the five most powerful women in British society, Leopold was conducting clandestine affairs with women in England and abroad, seconded by his invaluable agent, Stockmar.

From the day of Victoria’s accession, King Leopold had been dismayed to hear from Baron Stockmar, his agent at the Court of St. James’s, how

completely the Queen fell under her prime minister’s spell. Lord Melbourne for two and a half years had been both surrogate father and political mentor to the young Queen of England. Victoria adored Melbourne, laughed with him, relied on him, quoted him, adopted his friends and relatives as her own best friends and intimate companions. Cynical people such as the Duke of Wellington, Charles Greville, and Princess Lieven, the wife of the Russian ambassador, were saying that Victoria was in love with Melbourne though quite unaware of it. Such gossip could not fail to be distasteful to Victoria’s idealistic young fiancé.

The Coburg party, which comprised Victoria’s bitterly aggrieved mother as well as King Leopold and Duke Ernest, blamed Melbourne for the public relations debacle over the Lady Flora Hastings case and for the bedchamber crisis that had brought the Queen’s reputation so low in 1838. They were well aware that the prime minister at the outset had been, at best, lukewarm about Prince Albert as a husband for Queen Victoria. While at Windsor, Albert had met nothing but exquisite politeness and warm approval from Lord Melbourne, who was anxious to establish good relations with his beloved queen’s husband-to-be. But all the same, the prince from the outset was primed to see Melbourne as his chief rival for the Queen’s attention and regard, a secret adversary. The events in England over the next three months did nothing to change the prince’s mind on this point.