Welcome to Your Brain (32 page)

Read Welcome to Your Brain Online

Authors: Sam Wang,Sandra Aamodt

Tags: #Neurophysiology-Popular works., #Brain-Popular works

—that’s probably cultural—but that males typically think about the physical arrangement of the world

differently then females. Even female rats depend more on local landmarks to find their way around,

while males work from a mental map of space. For example, consider a maze in which the path to the

reward can be memorized by paying attention either to local features on the walls of the maze or to

distant features on the walls of the room. Rotating the maze so that it faces a different wall of the

room (which changes the distant cues) doesn’t affect the performance of female rats much, but it

causes the males to make mistakes. Changing local features affects performance more strongly in

female rats than in males. Similarly, if you hear someone say, “Go past the stone church on the left,

and then turn right a few blocks later at the tan house with the big pine tree,” you’re probably listening

to a woman. If you hear “Go south for 1.6 miles, then go east for another half mile,” odds are it’s a

man talking.

Did you know? Males are more variable than females

People tend to focus on the fact that more males than females score extremely well on

math tests, but it’s also true that more males score very poorly. Indeed, male scores are

more variable than female scores across many tests of mental abilities. This is another way

of saying that more males than females have abilities that are far from the average in both

directions. Like most sex differences, this one is small, and only becomes important for

individual people who are very far from average.

One possible evolutionary reason for this difference is that females are more important

to the production of children. If some males in the population go out and get themselves

killed, or fail to reproduce for any reason, the total number of children may be unaffected

because the remaining men can make up for the losses. On the other hand, if there are fewer

women, there are likely to be fewer children. That means that genetic changes that lead to

higher variability between individual men are more likely to survive in the population

because they’re more likely to be passed on to the next generation.

These differences extend to more abstract forms of spatial reasoning. For instance, starting with

an unfamiliar object photographed from one angle, men are faster and more accurate than women at

deciding whether a second picture is the same object seen from another angle. We know this

difference is probably due to hormones for one simple reason: if you give testosterone to women, they

suddenly get a lot better at the task. (In the long term, they also grow chest and facial hair, so this isn’t

a great solution for most women.)

The sex difference in mental rotation tasks is large, with the average man performing better than

about 80 percent of the women. For comparison, though, even this cognitive difference between the

sexes (one of the largest known) is smaller than their difference in height: a man of average height in

the U.S. is taller than 92 percent of the female population.

Men aren’t better at all spatial reasoning tasks, though. It’s not a coincidence that the woman of

the house knows where the mustard has ended up in the back of the fridge, but a reliable sex

difference. (You can try this with your friends: arrange a set of ten or twenty objects on a tray, let

everyone look at them for one minute, then rearrange the objects and ask everyone to write down

which objects are in a new location.) Women are better than men at remembering the spatial location

of objects, and their advantage at this task is as strong as the mental rotation advantage for men.

What about intellectual abilities? In 2005, Larry Summers, the president of Harvard, got himself

into a lot of trouble by saying in public that men are better at math than women. To be fair, what he

actually said was that more men than women have very, very high scores on standardized math tests.

It would be nearly impossible to look at a person’s math scores and decide whether the test taker was

male or female because there’s a huge overlap in abilities for most of the population. But among the

very highest (and lowest) scorers on math tests, men outnumber women dramatically. This imbalance

between the sexes might be a biological difference related to the male advantage in abstract spatial

reasoning, but it might also be the result of our culture telling women that they aren’t good at math.

For example, it’s possible to lower women’s math test scores just by asking them to write down their

gender on the first page of the exam (see

Chapter 22)

or to raise them by asking women to think about

high-achieving women before taking the test. (Please do try this at home!) In addition, test scores

don’t predict academic performance very well; in fact, males tend to do worse in college math

classes than their test scores would predict, while females tend to do better. So the jury’s still out on

whether the sex difference in high-level math scores involves differences in men’s and women’s

brains or in their cultures.

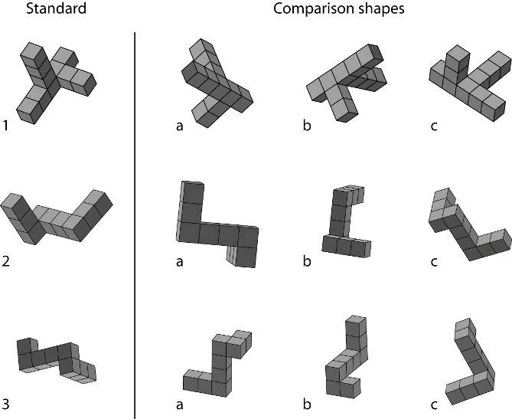

Quiz: How to think like a man

Which one of the three comparison shapes on the right is a rotated version of the

standard object on the left? Answer as fast as you can, using a watch with a second hand to

time yourself. (The answers are at the end, but don’t cheat!)

This test demonstrates one of the largest known differences between men’s and

women’s brains. We know a neuroscience professor who grew up as a woman and

eventually realized that she had always felt like a man and wanted to change her gender.

Being a scientist, she signed up for a study on sex differences in cognition that focused on

mental rotation of objects, like the test above. Running the study during the sex change gave

the researchers the unusual advantage that they could use the same person in the female

(before) and male (after) groups! Before the hormone treatment, our friend found the test

quite difficult, and felt that she had to slowly rotate each shape in her mind to see if it

matched the standard. After the testosterone injections started, the test got easier and easier.

By the end of the study, as a man, the correct answer seemed immediately obvious. This is

the clearest description we’ve ever heard of what this sex difference feels like from the

inside.

Answers: 1) b, 2) a, 3) c

As long as we’re being politically incorrect, the other place we find a lot more men than women

is in prison. Men are much more likely to get into trouble for violent behavior. That could mean that

men’s brains are biologically more inclined toward aggression, or it could just mean that men are big

and strong, so they’re more likely to use violence because it’s effective for them. Aggression is more

socially acceptable in boys, but that’s not the whole story, since many modern parents have found to

their dismay that boys have a stronger tendency toward violent play than girls do, even when the

parents are determined to treat their sons and daughters in the same way. Young male monkeys also

engage in more rough play than their female counterparts—and even prefer toy trucks over dolls.

Although aggression levels vary enormously between different cultures of the world, men are

consistently more aggressive than women in most groups. From this evidence, our best guess is that

both biological and cultural differences contribute to the greater incidence of violence in men.

People have been arguing for centuries about how men and women differ, so we don’t expect to

settle the issue here. As comedy writer Robert Orben said, “Nobody will ever win the battle of the

sexes; there’s just too much fraternizing with the enemy.”

Your Brain in Altered States

Do You Mind? Studying Consciousness

In Your Dreams: The Neuroscience of Sleep

A Long, Strange Trip: Drugs and Alcohol

How Deep Is Your Brain? Therapies that Stimulate the Brain’s Core

Do You Mind? Studying Consciousness

The concept of free will presents an apparent paradox to anyone interested in the philosophy of how

the brain works. On the one hand, your everyday experience—your desires, thoughts, emotions, and

reactions—are all generated by the physical activity of your brain. Yet it is also true that the neurons

and glia of your brain generate chemical changes, leading to electrical impulses and cell-to-cell

communication. The implication, then, is that physical and chemical laws govern all your thoughts and

actions—a proposition with which we wholeheartedly agree. Yet every day, we make choices and

act upon the world around us. How can these facts be reconciled?

It is undeniable that brain injury can lead to changes in behavior. The nineteenth-century railway

worker Phineas Gage was a responsible, hardworking man until a tamping rod blew upward through

his lower jaw and out the top of his head. Amazingly, he survived. However, afterward he became a

no-good, promiscuous layabout. His experience is the quintessential demonstration that our brains

determine who we are.

Free will is a concept that is used to describe what an entire person does. If the behavior of an

object can be predicted with mathematical precision, it doesn’t have free will. Therefore simple

objects such as atoms and particles don’t have free will. According to one point of view, free will is

ruled out by the idea that the output of our brains could somehow be predicted if we could know what

was happening in every cell.

However, a more useful interpretation is that our intuitions fail us when we try to predict what a

complex system is doing. No scientist has done a complete computer simulation of what even a single

neuron does biochemically and electrically—let alone the hundred billion neurons in an actual brain.

Predicting the details of what a whole brain will do is basically impossible. From a practical

standpoint, that’s a functional definition of freedom—and of free will. For a long time, neuroscientists

were reluctant to examine such questions because many of them felt that ideas like free will and

consciousness were so mysterious and undefinable that they would be impossible to study. But it turns

out that some aspects of conscious experience, at least, can be addressed experimentally.

It’s hard to study individual subjective experiences, the ones you might have wondered about in

those late-night conversations in school. What is it in brain activity that produces the quality of “cold”

or “blue,” in the sense of what I feel and imagine you might feel? This seemingly simple question

perplexes scientists, partly because it defines the question in terms of unmeasurable aspects of

experience, what philosophers who study the mind call qualia.

Did you know? The Dalai Lama, enlightenment, and brain surgery

Our fascination with the brain’s influence on moral behavior is shared by the Dalai

Lama, who made a speech to the annual Society for Neuroscience meeting in 2005. Sam

asked His Holiness whether, if neuroscience research someday could allow people to

reach enlightenment by artificial means, such as drugs or surgery, he would be in favor of

the treatment. His answer surprised us.

He said that if such a treatment had been available, it would have saved him time spent

in meditation, freeing him to do more good works. He even pointed at his own head, saying

that if bad thoughts could be stopped by removing a brain region, he wanted to “cut it out!

cut it out!” His homespun English and stabbing motions were unforgettable and would have

been more disturbing coming from someone not dressed in the robes of a holy man.

However, he felt that such a treatment would only be acceptable if it left one’s critical

faculties intact. We were relieved to hear this, since it rules out the prefrontal lobotomy, a

neurosurgical treatment invented by Egas Moniz and popularized with great enthusiasm in

the mid-twentieth century by the American psychiatrist Walter Freeman. Prefrontal

lobotomy is a radical procedure in which prefrontal lobes are disconnected from the rest of

the brain. It became popular in mental hospitals, primarily as a means of controlling

troublesome patients. The surgery did remove violent and antisocial impulses, but it also