Wendy and the Lost Boys (27 page)

Read Wendy and the Lost Boys Online

Authors: Julie Salamon

Wendy didn’t disagree. She loved the untamed impropriety of old-time show-business characters. But her real passion lay in developing the relationship between Jonathan and Cathy Maidman, the children who represented her and Bruce.

As the songwriters argued for more Catskills humor and broad comedy, Gerry Gutierrez pressed her to probe the darker vein of her family story. Wendy tried, writing and revising scenes and dialogue designed to reveal the pressures beneath the surface of the happy family: The mother can’t enjoy her vacation until she hears whether her son has been accepted to Harvard. The son can’t wait to fulfill the larger destiny he sees for himself. “I know I won’t grow up to be like Daddy,” Jonathan says. “He’s a very good man, but he’s not going to change the world.” The daughter wants to be loved. The father just wants them all to relax and have a good time.

But Wendy wouldn’t break the Wasserstein family’s unspoken pact of silence, not even behind the shield of fiction. In

Miami,

Cathy Maidman, speaking for Wendy, explains, “My mother told me never to tell our family secrets.” The play avoids conflict, culminating in a warm reconciliation between brother and sister in a heartfelt scene that reflected Wendy’s yearning but didn’t solve essential structural and thematic problems.

The reaction at readings was discouraging. Some of their Jewish friends were offended, thinking their ode to bad taste was mean-spirited and possibly anti-Semitic. Others thought the musical was funny but disjointed. Others agreed with Stephen Sondheim, who had come to one of the readings at Sussman’s invitation. “The tail is wagging the dog,” he told the songwriter. In his opinion they should focus on the raunchy nightclub singer and cut back or eliminate the rest.

Dissecting a failed play is like analyzing a failed marriage. Everyone has a point of view; no one has a satisfactory answer. But one thing became clear: As time wore on, everyone besides Wendy ran out of steam. She continued to write furiously, bringing in new scenes and revisions every day. But the songwriters didn’t keep pace, and the director seemed to have checked out. Feldman and Sussman had been counting on Gutierrez to do what he’d done with so many other shows, including

Isn’t It Romantic

—to dazzle with stage design, pacing, whatever it took to set a piece spinning.

But he couldn’t do it. Unable to find a way to make

Miami

work, ashamed of failing Wendy, Gutierrez fell into one of his periodic funks. “It was always a roller coaster with him, part of the ‘contract’ when doing his shows,” said Scott Lehrer, the sound designer. “He was an absolutely brilliant but difficult human being. This was a show that was not jelling for him, and he had a hard time dealing with that.”

For the entire month of January 1986, Playwrights Horizons presented

Miami as

a musical-in-progress, a workshop that was closed to the press. The entire run was sold out, partly because of the popularity of

Isn’t It Romantic

and also because Sondheim’s

Sunday in the Park with George

had been tested at Playwrights exactly that way and had gone on to become an esteemed artistic triumph on Broadway.

It was clear, by the end of the run, that

Miami

wasn’t going to follow in the footsteps of

Sunday in the Park with George.

On the final night, Ira Weitzman, director of musical theater at Playwrights Horizons, tried to inject a celebratory note into the subdued cast party. He brought in a flamingo he’d designed out of chopped liver, an homage to the outlandish culinary touches that had prevailed at the Miami hotels of Wendy’s youth. Weitzman knew that it was a futile gesture. While musicals could find their spark just when it seemed everyone was exhausted, that wasn’t likely to happen this time.

“If your energy has been spent leading up to that point, a show can flounder,” he said. “That’s what I remember about

Miami.

”

Subsequently André, Gerry, Wendy, and the songwriting team met at a restaurant in Chelsea, to contemplate the various pieces of advice they’d received. They emerged from lunch with a vague plan on how to move forward. But the momentum, already flagging, stopped altogether when lawyers and agents weighed in. The project died.

Wendy was deeply disappointed. “I guess I do have some pain about Miami,” she wrote to André two months later. “But that’s not the real pain. I guess it’s that in some way I feel that Gerry and Jack and Bruce [Sussman] didn’t come through for me, and I, therefore, couldn’t come through for my play or for the theatre. It’s a frustration.”

Wendy never worked with Gerry Gutierrez again, though they remained close friends. Bruce Sussman and Jack Feldman remained a team a while longer, and then they, too, went their separate ways. As for André, he blamed himself. “I wasn’t really the captain of the ship,” he said. “The problem was that nobody was the captain of the ship.”

After four years of effort, and a brief run as a Playwrights Horizons workshop production,

Miami

was put into storage, where it remained.

Its failure continued to nag at Wendy. At thirty-five she remained in flux. “I feel that things are changing, or rather, I haven’t decided how they would change,” she wrote to André.

Miami

’s unsatisfactory denouement represented her feelings about Bruce, family, heritage, ambition, the future. For her, she said, “it seems unfinished business.”

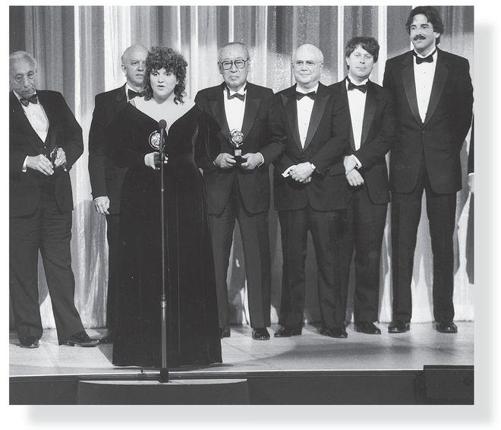

WENDY AND HER PRODUCERS ACCEPTING THE TONY FOR

THE HEIDI

CHRONICLES

, WHICH ANDRÉ [SECOND FROM RIGHT] KNEW, THE MOMENT

HE READ IT, WOULD BE AN “AMERICAN IMPORTANT PLAY.”

Fourteen

ROOMS OF HER OWN

1986-87

On June 2, 1986, Newsweek

magazine terrified the women of Wendy’s generation. The cover story—headline, “The Marriage Crunch”—informed readers that for female college graduates still unmarried at thirty, the chances of finding a husband were one in five. At age thirty-five their chances were almost nil, 5 percent.

12

By then Lola Wasserstein had nine grandchildren, each offering a fresh opportunity to remind her youngest (still-unmarried) daughter, “Your sister-in-law is pregnant, and that means more to me than a million dollars or any play.”

The pressure came from every quarter. While the Wassersteins proliferated, Wendy’s friends and acquaintances had also begun coupling and were beginning to have children. That summer Chris Durang had a small part in a movie (

The Secret of My Success

), where he met a young actor named John Augustine; they became lifelong partners. Sigourney Weaver was married. James Lapine had married and in 1985 had a daughter with Sarah Kernochan, a versatile woman who wrote, produced, and directed films and was an accomplished musician as well. Meryl Streep gave birth to her third child that year (there would be a fourth).

Wendy took steps toward acknowledging her independence, or spinsterhood, depending which generation was talking. In 1985, at age thirty-five, she finally got her driver’s license and bought a car. After years of rentals and sublets, she moved into a home she owned, an airy sixth-floor apartment at One Fifth Avenue, an Art Deco tower just north of Washington Square, an enviable address for anyone and perfect for her: Greenwich Village, to satisfy her bohemian urges, but definitely not a walk-up. One Fifth bespoke elegance and accomplishment. It was a doorman building equipped with uptown perquisites, including a grand, wood-paneled lobby and the bragging rights that came with neighbors like Brian De Palma and Paul Mazursky, celebrated filmmakers, and Michiko Kakutani, book critic for the

New York Times.

Perhaps the most attractive feature was proximity to André Bishop, who lived on Waverly Place, a short walk away.

During

Miami

the producer and the playwright had begun spending even more time together. André appeared frequently in Wasserstein family photos. He and Wendy had traveled to Oxford, England, to meet his half brother, who was studying to be an Anglican theologian. There Wendy experienced her first traditional Christmas celebration—nothing like previous Christmases spent at Miami Beach nightclubs, or watching the Radio City Rockettes, or her Orphans’ Christmas in New York. Before she left for England, she consulted friends about what gifts to bring and what to wear. During Yuletide at Oxford, Wendy ate lobster Newburg and drank champagne, according to André’s family custom, listened to medieval carols, and then everyone gathered to trim the tree with tinsel and lights.

Wendy was both moved and terrified, not quite knowing what to do when Fay, André’s mother, handed her an ornament and encouraged her to hang it.

“I was seized with panic,” Wendy wrote. “How could I tell this woman that I’d never done this before? How could I explain to her that when I put the ornament on the tree, a flying ham, all the way from Flatbush, might come crashing through their Oxford window?”

Muttering “Oy,” she took a deep breath and found an empty spot to hang the ornament, right in the center of the tree.

“The house remained standing,” she noted gratefully. “The carols went on playing. No bushes spontaneously combusted and no flying hams pelted the window.”

In subsequent years she and Fay became Christmas regulars—not in England but on Park Avenue in New York. Lunch at the Colony Club became an annual Christmas event for Fay, Wendy, and André. Every year Fay—wearing her customary gloves and Schlumberger brooch—presented Wendy with an elegant handbag. Every year Fay’s escort introduced Wendy to General MacArthur’s widow. Every year they ate plum pudding.

Being embraced by André’s family gave Wendy entrée into the world that had seemed far out of reach when she was a student at Calhoun, envying the Brearley girls and their apparent ease. André’s elegance wasn’t learned, it was inbred. He had begun wearing Brooks Brothers in prep school; now Wendy accompanied him when he purchased his annual supply of fifteen oxford button-downs, the heavier weight.

She regarded his fastidiousness with tender amusement. “Seized by a moment of wild-and-crazy abandon, he also purchased two striped Egyptian-cotton shirts without collar buttons,” she wrote. “Following this act of unrestrained depravity, poor André was troubled for at least three hours.”

Whenever he needed a new suit, he asked Wendy to go shopping with him. Unlike Chris Durang, a reluctant shopper who liked thrift shops and bought his slacks at the Gap, André happily followed Wendy to Saks and Barneys. Wendy wanted to buck social convention, but she was comfortable in the class to which her family had climbed. Her feminism was not commingled with egalitarianism. She liked cabs, dry cleaners, doormen, and Bergdorf’s—though she would show up at parties wearing high-topped sneakers with a designer dress.

After Wendy moved into One Fifth, she and André spent almost every weekend together and often went out to dinner during the week. Her day began with a call to him, to catch up on gossip or just to say hello. It was André who converted Wendy into being a cat lover. “He convinced me to drop my fears of becoming a L.S.W.W.C.—Lonely Single Woman With Cats—and replace them with the joy of having a warm, intelligent feline by the fire,” she wrote.

André was besotted with his own Aristocat, an elegant feline named Pussers. He dragged Wendy to the ASPCA, where they visited the back room that Wendy called “kitty skid row.” André discouraged her from taking home the lumpy furball she was inclined toward. Wendy told André she wanted a hot-water bottle of a cat, one that considered cuddling a form of exercise.

He ignored her and looked at the forlorn rejects imprisoned in their cages. He spotted a mature orange calico and asked the manager to release her. The cat strutted slowly out, with a regal lift to her tail. André picked her up and began to pat and tickle her head.

“I think she’s the best cat,” he said, nuzzling her ears.

When Wendy hesitated, André said, “I’m telling you, this is the best all-around cat. She’s older, she’s pretty, and we know she didn’t come from the street.”

The ASPCA person noted Wendy’s anxiety and asked, “Are you sure you know how to take care of a pet?”

André answered. “She does,” he said.

Wendy named the cat Ginger Joy. She later wrote about that day, from the cat’s point of view. In an unpublished story, “A Happy Story” by Ginger Wasserstein, Ginger describes André: “He is my guardian angel, my knight in shining armor.” Wendy may have put the words in her kitty’s mouth, but the feelings were hers.

André had become, quite simply, the love of Wendy’s life, though nothing else about their relationship was uncomplicated.

They spent summer weekends in his house in East Hampton, a modest place notable for its previous owner, Alger Hiss, the diplomat and government lawyer accused of being a Soviet spy during the Cold War. When André won grants to go to London to see theater and meet people, Wendy went along. They sailed together on the

Queen Mary

and traveled to Maine. They were intimate, holding hands and often sharing a bed but not sex.

André had a calming affect on her. When she was frazzled by having too many things to do, or jumped to weird conclusions, or worried about things not worth worrying about, he told her, “That’s totally insane.” That particular phrase became an inside joke, but it was also reassuring.

Discussing Wendy with his therapist, André came to understand that he was drawn to her because of his mother, toward whom he felt both love and anger. “She really didn’t bring me up very well,” he said. “She wasn’t careless or cruel, she didn’t not provide for me. She just wasn’t that interested. She wanted her new husbands, and I shut her out. She wasn’t the warmest, most sympathetic person in the world unless you really dug down. Wendy was kind and generous. I always gravitate toward warm, caring women, the mothers I never had, the sisters I never had.”

When marriage entered conversations between him and Wendy, André was interested, even though he was openly gay—with one major exception. He hadn’t discussed his sexual preference with his mother. Her prejudices and fears ran deep, and André preferred to avoid confrontation.

Fay let him know she would be pleased to have Wendy as a daughterin-law. Her endorsement wasn’t the main reason he seriously considered marriage, but it lent weight to the idea.

“Wendy always tried to say, ‘Oh, let’s get married, let’s have children,’ and be sort of lovey-dovey,” said André. “I think she thought, ‘At some point he’ll marry me and we’ll have a strange but happy relationship.’ I thought it, too. Seriously. I had nothing else in my life. It wasn’t like I had all these boyfriends and then there was good old Wendy. It wasn’t like that. She was the primary relationship in my life for a number of years . . .

“I deeply loved her,” he said. “Probably in my life she was the closest person ever to me.”

There would come a time when he wouldn’t be able to clearly remember the details of those carefree days of wandering around Greenwich Village without a destination, having dinner at two in the morning. He never forgot, however, why Wendy was so important to him. “I was always mopey and unhappy, or anxious, and Wendy was very, very sympathetic,” he said. “We were helping each other grow up.”

The idea of marriage between him and Wendy, which seemed improbable to others who knew them, seemed fairly straightforward to him. “I thought about marrying Wendy because I loved Wendy,” he said. “There was no real mystery.”

Wendy performed many functions thought of as “wifely.” Not just shopping and providing companionship and encouragement, but setting the social agenda. “I was very clear all the time about what I wanted to do in theater but very unclear about everything else,” said André. “I was insecure and uncertain and shy.” Wendy cleared the path, plunging in, making introductions. “I had someone to go places with, and it was wonderful,” he said.

He saw many reasons for them to be together. “I cared deeply about her success, because I believed deeply in her as a writer,” he said. “We had wonderful times together. We had a lot of friends together. She made no demands on me. She was sympathetic and cozy, and I was also there for her. We were very, very compatible. Stranger marriages have happened.”

To a later generation, raised on open discussion and increasing acceptance of gay rights and same-sex marriage, this romance might seem quite peculiar (or not). Certainly in the eighties, everything was up for grabs. More and more people were coming out of the closet, but just as many remained inside. Gay men and women had historically married straight partners, for propriety’s sake; both Wendy and André knew people with secret lives. Old customs die hard.

In early 1987, infatuated with André, Wendy began mapping out a screenplay for

The Object of My Affection,

a novel by Stephen McCauley about the relationship between a gay man and his best friend, an eccentric young woman. Wendy worked on the project, on and off, for years. The story—encapsulated by McCauley in a poignant reflection by the main character, the gay man—must have struck home:

There isn’t much to say about my relationship with Nina except that we loved each other and took care of each other and behaved a little like best friends, a little like brother and sister, and a little like very young and very tentative lovers. I suppose the best way to describe our friendship is as a long and unconsummated courtship between two people who have no expectations. Sometimes when we came home late from dancing or a double feature, there was an awkward moment of hesitation as we said good night and each went off to our separate rooms, but that was only sometimes. I think we both valued our friendship too much to make any overtures at exploring the murky and vague desire we felt for each other. I think we were threatened and excited when we were mistaken for a couple by the neighbors. . . .

Wendy began pushing André for answers about their future, leading him to a realization. She wanted children, and he firmly believed he couldn’t do that. “I didn’t think I would be a good father,” he said. “I had such an awful, remote family life that I was afraid of inflicting whatever I had inherited, or learned, on a child.”

André was gay and a worldly man of the theater, but in many ways he was conventional, with old-fashioned ideas of what a marriage should be. He realized that he and Wendy were too young—still in their thirties—to commit to a life without sex, and an “arrangement” seemed too cold-blooded.