Wendy and the Lost Boys (26 page)

Read Wendy and the Lost Boys Online

Authors: Julie Salamon

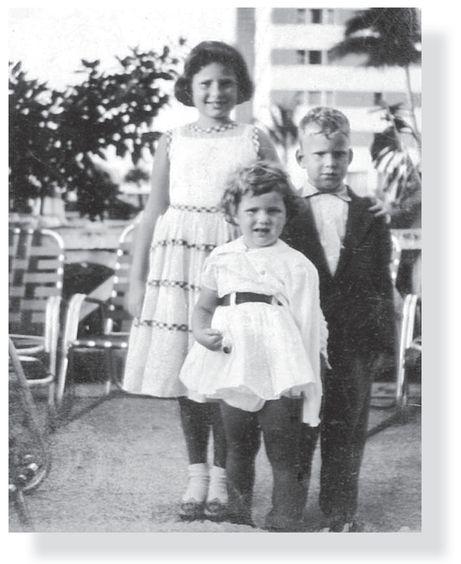

WENDY ALWAYS FELT NOSTALGIC ABOUT

FAMILY TRIPS TO MIAMI BEACH. HERE SHE IS

WITH BRUCE AND GEORGETTE.

Thirteen

MIAMI

1984-86

Wendy’s next play

,

Miami

, took her back to childhood and her relationship with her brother Bruce. Perhaps inevitably, given the complexity of their relationship, she was never able to get the play to work.

Wendy had never stopped loving Bruce, but sometimes she wasn’t sure she liked him anymore. The two of them emerged into the spotlight together, as they ascended into the top echelons of their hometown to become representatives of New York’s lifeblood industries, culture and commerce. Wendy became known for her openness, Bruce for his secrecy. Both of them sought attention, in very different ways. Neither was as clear-cut as they both seemed.

In late 1983, as

Isn’t It Romantic

opened at Playwrights Horizons, Bruce was orchestrating the largest takeover in American corporate history, Texaco Inc.’s $10 billion acquisition of Getty Oil Company, which had already announced it was going to merge with Pennzoil. With this deal, as codirector of mergers and acquisitions at First Boston Corporation, he could claim the distinction of being the investment banker involved in the four largest mergers in U.S. history.

By then Bruce had frequently been quoted in articles in the

New York Times

and the

Wall Street Journal

and had developed a reputation for eccentricity and arrogance, showing up for meetings wearing decaying sneakers, no socks, and faded jeans with a hole in the seat. In a financial journal, he explained the difference between him and Joseph Perella, codirector of M&A at First Boston, the man who’d hired him. “If the company is run by a 65-year-old self-made type who doesn’t want to have people telling him what to do, he’s usually more comfortable dealing with Joe,” said Bruce. “If he’s a 45-year-old boy-genius type, he may be more comfortable with me.”

Wider recognition, outside the business pages, came in May 1984, with a long profile in

Esquire,

under the title “The Merger Maestro,” with an ego-inflating subhead: “At thirty-six, Bruce Wasserstein plays in the high powered world of corporate mergers, where the prizes can be worth billions. No matter who loses, he always wins.”

Two months after the

Esquire

article appeared, Tom Wolfe began writing installments of a novel in

Rolling Stone,

as Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray had done a century earlier. Eventually these installments were reconfigured as Wolfe’s hugely popular 1987 novel

The Bonfire of the Vanities,

which chronicled Wall Street excess in the 1980s and then came to represent it. In

Bonfire,

Wolfe created the designation for men like Bruce Wasserstein, who treated the world’s financial markets as an extension of boyhood Monopoly games. They were, Wolfe wrote, “Masters of the Universe.”

Their motto was succinctly stated in

Wall Street,

Oliver Stone’s 1987 movie: “Greed is good.”

As the Wasserstein siblings gained prominence, strangers wondered how the two could have emerged from the same gene pool: the warm, lovable playwright, trying to find a resonant message for her peers, and the ruthless banker, concerned with making himself and his business partners rich without apparent regard for the repercussions on the larger society.

Their lives had diverged. Wendy lived in a series of sublets, while her brother moved from a ten-room Fifth Avenue apartment to one that had fifteen rooms (and six bathrooms, four fireplaces). She escaped to the Hamptons to write in an apartment over a garage; he bought a sixteen-acre beachfront estate, eventually becoming one of the biggest taxpayers in East Hampton, a community with a disproportionate allotment of millionaires and billionaires.

Yet the siblings were as similar as they were different. They were smart and ambitious and had gargantuan personalities, hers projecting warmth and his, gruff superiority. Despite appearances Wendy was as guarded as Bruce, but she used selective revelation to deflect outside probing. They were drawn to fine things but were often unkempt. They struggled with their weight and shared a particular look; strong, expressive faces notable for character, not beauty. They gravitated to power and were fiercely loyal to people they cared about. But Wendy’s circle seemed to endlessly expand while Bruce’s affection was tightly controlled. He extended it lavishly to his immediate family and more modestly to a very select number of friends and relatives.

Bruce was not happy with Wendy’s public disclosure of personal detail. He took Lola’s childhood lessons to heart and was intensely private about personal matters. In his business the control of information determined success or ruin; Masters of the Universe must be infallible. He found his sister’s plays to be too revelatory, too poignant, too Jewish. He felt she turned their parents into caricatures. He didn’t appreciate the inside joke in

Isn’t It Romantic,

when Tasha Blumberg refers to her non-Jewish daughter-in-law as “Christ.” His wife, Christine, looked stricken, when she first heard the line but took the poke in stride.

Bruce was competitive by nature. Decades after he and Wendy had applied to the Ethical Culture School, he discovered his little sister’s diary entry: “For the first time I got a higher IQ score than Bruce!”

Bruce was sixty years old when he learned what his then-eight-year-old sister had written.

Almost a half century had passed, but his answer was instant. “That’s not true,” he said. “I know the test, I know the scores. . . . It’s not true.”

Still, they were bonded by memories no one else shared, even if their versions of the past didn’t always jibe.

“We were very, very close,” said Bruce, no elaboration.

Elaboration was Wendy’s forte. “Sometimes I wonder whether many of my current friendships with men aren’t influenced by those years with him,” she wrote in a largely affectionate article. “Not that I’ve ever again latched onto anyone who wanted to carve a B onto my pajamas. But I derive great comfort from long-term friendships with men—brother figures actually. We don’t play emotional games with each other, and I don’t worry about whether they’ll ever call me again. Nonetheless, I still fall into the trap of thinking, ‘Oh, he’s brilliant, he’s smarter than I’ll ever be.’ And they no doubt get pleasure of a sort out of being around someone who feels this way.”

The divergence of their paths bothered her. “We travel in orbits that rarely intersect, and in some ways we’ve become enigmas to each other,” she wrote. “There’s little I can say about my life that I think he will easily understand—I’m not making mega movie deals or marital deals, and I don’t have a game plan, a strategy. His secretary still places his calls to me; when he gets on the speakerphone he inevitably bellows ‘What’s new?’ And I can’t help wondering whether what I say has any relevance for him at all.”

She might criticize him, but no one else should dare. While Wendy was in the New York University library, working on the screenplay of

Isn’t It Romantic

(never made into a movie), she diverted herself by thumbing through

Powerplay.

The bestselling memoir by Mary Cunningham, an attractive executive, described her rapid ascent at the Bendix Corporation and then her public humiliation after being accused of having an affair with her boss, the company chairman William Agee, whom she later married. A reference to Bruce prompted Wendy to write a huffy letter to Cunningham—not to proclaim sisterhood but to defend her brother, who had been hired by Bendix for a takeover play:

I doubt very strongly that my brother ever said, “It must be nice to have a wife who does more than cook” and furthermore question the claim you influenced Bruce’s late awakening to feminism.

Let me tell you a little about the women in my brother’s life. I am a playwright, my play Uncommon Women has been performed at over 1,000 colleges and my play Isn’t It Romantic is running in its 8th month off Broadway at the Lucille Lortel Theater. My sister Sandra Meyer is president of the communications division of American Express. My sister-in-law Chris Wasserstein is a psychotherapist . . . and my mother is a dancer who at age 65 still dances at least 5 hours a day. Furthermore, none of the above women cook, except my sister who can make an extraordinary cassoulet.

Bruce has never, in fact, been around a wife who only cooks (and if he were, what an extraordinary cook she would be!). Because Bruce, in a very exceptional way, has always supported the women around him. . . .

M

iami

began after Wendy told her ex-boyfriend, Ed Kleban, that she was interested in writing a musical. The story would be inspired by the Wasserstein family’s Miami Beach vacations in the 1950s. Kleban recommended a songwriting team, Jack Feldman and Bruce Sussman, fresh off their success with the 1978 Barry Manilow hit disco song “Copacabana.”

Wendy and the songwriters understood one another. “We grew up in a similar world and all had the same Miami experience,” said Sussman. He was from a middle-class neighborhood in Queens; Feldman’s family had made it to the more affluent Five Towns of Long Island. As Wendy talked about her childhood winter vacations, Sussman was flooded with memories from his own childhood, when his family used to drive to Florida from New York over the Christmas school break.

It was easy to mock the pretensions of the Miami Beach crowd—the women dripping jewelry, the men dripping sweat, all of them broiling themselves mercilessly to acquire the souvenir tans that signified they were rich enough to vacation in Florida. But Wendy and her collaborators remembered how glamorous it seemed to them as children, a giddy interlude—let’s rumba!—in lives preoccupied with work, a break from the perpetual climb toward elusive aims.

“The holidays were a time for the family to catch Harry Belafonte, build sand castles on the beach, avoid jellyfish, and dance with Dad under the stars to a Latin combo,” Wendy recalled.

They traded anecdotes from their youth. Sussman had a younger sister who always complained that he was the prince, just as Wendy complained about Bruce. One day Wendy burst into tears and told her collaborators about Abner. “She just talked about how difficult it was, the choice the family made,” Sussman said. “She just sobbed.”

For a couple of years, while Wendy worked on

Isn’t It Romantic,

the three of them met sporadically. Wendy became fascinated by a comedian named Belle Barth, a transplanted New Yorker who became a Miami Beach character, known as the raunchiest female comic of her day (live recordings of her acts were released as record albums, including the titles

If I Embarrass You Tell Your Friends

and

I Don’t Mean to Be Vulgar, But It’s Profitable

). Wendy saw dirty-mouthed, rule-bending Barth as a pioneer in her field and good material for a musical. She began to see the comic’s story as a way to revisit her own childhood, by having a close-knit, ambitious New York family confront the larger world represented by Barth and Miami Beach itself.

Gerry Gutierrez joined the project after the Playwrights Horizons’ version of

Isn’t It Romantic

became a hit; both he and Wendy wanted to work together again, and both were eager to do a musical. They’d survived a disappointing experience with a CBS comedy series, a failed summer replacement show called

The Comedy Zone.

Wendy was one of the writers; Gutierrez had been fired as director halfway through taping. Their shared misery made them even closer than they had grown during the Los Angeles run of

Isn’t It Romantic,

when they were together so much that Gutierrez joked, “We might as well be married.” Whenever he called Wendy, he greeted her with a lyric from

Fiddler on the Roof:

Do you love me?

She would sing back:

I’m your wife!

André was ready to produce their new work and scheduled a workshop production of

Miami

for the end of 1985. With a deadline now looming, Wendy’s sporadic meetings with the songwriters intensified to a regular schedule, usually five times a week.

At first Feldman found the playwright’s work habits annoying. “She would come in late to a meeting with notes and dialogue scrawled in a spiral notebook, that she had written on the bus, on her way over,” he said. “It seemed like she hadn’t really given a lot of thought to what we were going to deal with that day.” Over time he realized that her sloppiness was a front for her insecurity. “This was a way of saying, ‘Well, if it isn’t good, it’s because I really didn’t have time to work on it,’ ” he said. “She was so sweet and personable and

heymish

[Yiddish for cozy, snug] that it was very hard to—and this may have been more deliberate than I knew at the time—it was very hard to reprimand her or get angry. But it could be frustrating.”

The collaboration grew strained as the months dragged on and it became evident that the songwriters and the playwright had different interests. Sussman and Feldman were enthusiastic about Belle Barth, who Wendy fictionalized as Kitty Katz. They could hang a show on Katz and the pretensions of the nouveau riche New Yorkers who flocked to Miami Beach. The overdone hotels and their overeager patrons were ripe for satire.