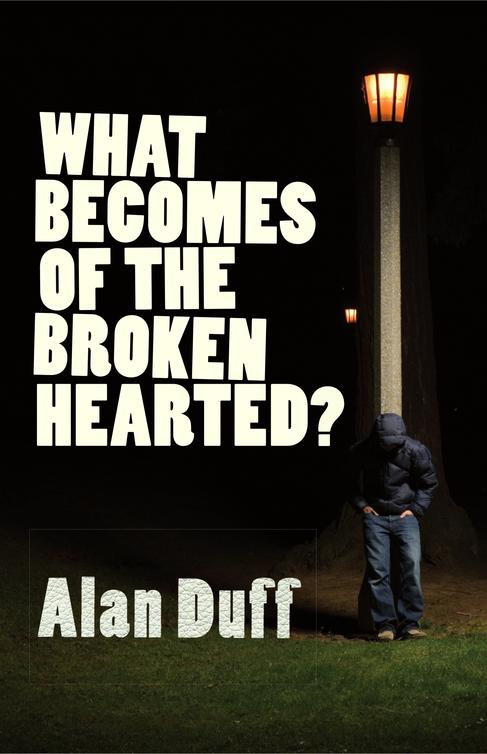

What Becomes of the Broken Hearted?

Read What Becomes of the Broken Hearted? Online

Authors: Alan Duff

THE PRIZE-WINNING, PASSIONATE AND UNCOMPROMISING SEQUEL TO THE BLISTERING CLASSIC NOVEL,

ONCE WERE WARRIORS

‘SHE ALWAYS CAME THE FOLLOWING DAY FOR A VISIT ON THIS YEARLY REMEMBERING; IN FACT POLLY HEKE CAME SEVERAL TIMES A YEAR AND HAD DONE FOR THE LAST TWO, FROM WHEN SHE HERSELF HIT THE SAME AGE AS GRACE’D BEEN WHEN SHE, UH, WHEN SHE LIKE KILLED HERSELF.’

THE SEARING POWER OF ALAN DUFF’S MASTERPIECE

ONCE WERE WARRIORS

ROCKED A NATION AND WAS ACCLAIMED AROUND THE WORLD.

WHAT BECOMES OF THE BROKEN HEARTED?

IS THE CHALLENGING, POETIC SEQUEL, TAKING UP THE STORY OF THE HEKE FAMILY SIX YEARS AFTER GRACE’S SUICIDE.

THE NOVEL WON THE NEW ZEALAND MONTANA BOOK AWARDS FOR FICTION AND WAS MADE INTO A FILM.

ALAN DUFF

To my father, Gowan.

My grandfather, Oliver.

And to love mending most things.

Thanks to G. K. and K. K. for childhood memories.

J

AKE

H

EKE

WOKE

from a dream in his sheetless bed, what he’d been born to, and never had all those years of being married to Beth (oh, Bethy) managed to change his ways; he had never been able to understand why she didn’t prefer the feel of blanket — man, it’s the feel of the wool, like my own fucken sheep keeping me warm, I like. A man’d cracked her once over her telling him he was a filthy animal just for not bothering about sheets when she’d been away for a few days to a funeral and come back to the house she said was a mess, which it was — ’cept a man’d had some of the boys still there, out in the kitchen finishing off the keg even though it was near flat, long’s the party kept on (but that was in them days, years ago) — so he told her why don’t you fucken clean it up, and when she went upstairs and saw the bed got no sheets (I don’t know what I did with them, I musta thrown them off when I was drunk and got into bed with my sheep — hahaha! — an’ flaked) that’s when she came back down and called me what she did front of the boys. Well, naturally a man gave her one, and I ain’t talking a root, eh, boys! HAHAHA! had to laugh, and not as if it was a hiding, just a backhander to let her know, don’t talk to me like that front of my mates. Or a man’ll never be able to show his face again. But that’s how a man thought back then, ’bout, what, five, six years ago? No, longer’n that, the sheet incident, that musta been ten years, the six is how long we been apart. (That long? We been apart that long? Well I’ll be: a man’s been hurting for her that long?) Now, he wasn’t so comfortable about — well, a lot of things.

Rubbing a hand over the back of his processed sheep (there, there, boy, Jakey’s here) and giggling inside that he thought of the blanket in its original, living form, and while his hand was down there he may as well get rid of that; and he thought of Rita, even though he’d had her heaps of times, because she was the best and she was still available, and she did it with a kind of instant intensity. Jake couldn’t quite come up to the same level — not the act nor his

understanding

of her own part in it (I just lap it up!) that in his more clear moments of thought he saw as a tap Rita turned on — of love but with a capital L. Yeah, Love it was. For not just himself, Jakey, but —

and this confused him even more — herself. (So how does she fuck so good if she’s loving herself?) Ah, fuck it. He was finished with himself in a few minutes anyrate and then nothing about sex gave him a bothering thought and as for love or Love, well that was

different

after a man’d shot. For a while anyway. And anyway Rita Bates was one of those strong women wove, well that was

different

after a man’d shot. For a while anyway. And anyway Rita Bates was one of those strong women who decided her relationships on her terms, so a man knew he had to ring first (from the next door’s phone) and not just turn up when he felt like it, and sometimes she might say no, not this week Jake, I’m busy, meaning she had

someone

else, or her period, or she was just showing a man he needed her more than she needed him. Yet when he did get the yes from her she acted like he was the only man in her (comfortably) over-weight life. So he thought he may as well get up, now he’d had her in his mind. But then somewhere in his head he felt a kind of grabbing. It was the fucken dream. A man’s mind is trying to grab what the dream meant. And then it hit him, it was an actual physical jolt.

It was this picture, with these groups of people spread across a rocky landscape of all sorts of things you see in ordinary life, and some things you didn’t, ’cept in dreams, like plants talking to each other and changing between being talking plants and people you knew, and colours that went with music, both of which you knew and yet you didn’t; they were big groups, small groups, in clusters and talking (urgent talking) or busying (fucken cunts hurrying everywhere yet still somehow connected) and what they had in common was, humming. Mmmmmmmmm-uhhhhhh like that, like an engine going on quiet but steady idle. (And me, I’m up on this low rise of hill, Jake The Muss like I used to be, looking down on these cunts — well, they weren’t cunts, only if they were gonna try me on, or only if they were out to hurt me when I wasn’t out to hurt them, not to start it, ask anyone: Jake The Muss never started the scraps. I finished them!) And these groups became engines, or each one’s centre did, how things evolve in dreams, and a man’s smiling to himself cos he’s back where he belongs, on top. Till it occurred to him the reason he wasn’t down there with them, one of the groups, was he didn’t know the tune. Even if it was tuneless. The note then; a man didn’t know the note and had never known it. That was the physical jolt he felt in recalling the dream: that he didn’t belong nowhere.

For some reason the largest group were Chinese — fucken chinks, never give up trying to take one lousy spare rib out of a man’s feed even after all these years a man’d given the slits such loyal whatsitsname, custom. Changing their car every year for another brand new one, as if I fucken care what kind of car they drive. There were several groups of honkies, and yet they were humming the same one-note constant as the Chinese. And a man was looking around, to find a group of his own kind, which (thank God) he did, it was a wonder he hadn’t spotted them first for their humming was musical and so he started off down the hill toward them, till it came to him that though they were making something musical, melodic, of their humming, they were distracted by it. That’s what his eyes back into the dream were telling him: the ole Maori boys — and some girls — were having a good time (as usual — hahaha!) partying up the large whilst the honks and the chinks had the old heads down an’ white bums and yellow bums (with the sideways slits, so their shit must come out … — have to think about that one — like liquorice straps. HAHAHA! one thing I’ll say, Jake Heke, you’re still funny. Liquorice straps, hehehehe, smell like soya sauce.) And he started on down again, over this hard stony ground, and grey outcrops of larger boulders down there amongst the outcrops of busy whites and Chinese and their engines steady and constant, and a man knowing where he was headed and yet with doubts starting to get at him.

Or they did till he got down onto the flat and that closeness of other human physical presence brought out the MAN in him, so he lost a lot of his thinking and became almost a purely instinctive animal, and giving off the vibes of: Don’t you touch me,

muthafucka

, not ’nless it’s to pay homage, or show friendliness, or Jake’ll waste you. Heading for where the partying action was and finding he had hurry in his footsteps, as if to get away from that now

irritating

fucken mmmmmm-uhhhhhh-ing, over to that party Smiling, glad in himself at hearing his name — Jakey! It’s Jake The Muss! Hey, bro! Come and join us — and then he was running. For them. To them. With this … this … (I dunno — Yes, I do know.) This sense of belonging.

Plunging himself into them, the welcoming group. Thinking to himself, now this’s a tune I do know. And yet … yet … a man

was hardly into the swing of it when his inner voice was telling him he didn’t know this tune either. (But I knew all the words to the songs they were singing …) And next he was stumbling, cut, bleeding over the sharp rocks, and every time he fell and was briefly and painfully down there on the hard ground, harder than his own muscles, he saw each flinty stone, their every tick and comma of layered grain, he saw brilliantly coloured red ones with the blue sea blended like long ago water caught in them when they musta been volcanic stuff connecting red hot with water till the temperature musta been cooled enough to marry with, not turn to vapoury steam, that water. Right by the groups of chinks and Pakeha white maggots to another group of brownskins like himself and the group he’d just left, ’cept they were droning the same working note as the others all over this valley of rocks, which he saw each group was building into constructions, houses and buildings, in shapes and beginning layouts of a complexity he for some reason understood. But he didn’t understand why he understood, he was no carpenter, he hadn’t even worked on a building site even though in his heart of hearts he’d long wanted to, walking past sites in town and seeing the miracle of a

several-storey

office building sprouting from the ground, from someone’s mind and someone else’s materials, and the mysterious glue of it: money, no not money but finance, money was the rub-together stuff that never lasted long, only from one payday to the next, or when he was on a government benefit it didn’t even last that long, there was always a day, often two, short, of having nothing to eat or smoke or drink, just resentment and envy and a kind of hating confusion at it all, the process, of not being part proper of the

real

process. Putting together those office buildings wasn’t cash, the folding stuff, it was finance. Nor did he understand why he kept falling over, let alone seeing the stones and rocks in such striking clarity and colour. But then he did.

It was cos his fucken eyes kept closing, a tiredness, a deepest sleepiness kept coming over him, so down he’d go. But up again. He was Jake The Muss, not Jake the Wuss. And look, he was making progress for that other group, of Maoris just like him, least the same colour and about the same features (I might be a bit more handsome, cuzzies!)

He reached the group. But they took no notice of him. Hey? he went, but no one looked up. They were doing what the other human outcrops were doing: mmmmmmm-uhhhhh and steadily a surround of arranged rocks was encircling them. One minute Jake on the inside. Next he was out looking in (like walking down the changing main street of Two Lakes, all them new restaurants and café places, the big windows, shutters, slatted openers of nicely stained wood even I ’ppreciate ’em) at something and someones he was never gonna be part of, but never. Like going past a new era (or even worse, a party) he wasn’t invited to.

So he got up out of bed. Angry at the dream, because it’d promised such insight, a look at not just himself but the world he was living in that’d always confused him (I admit that. Now I do) and it turned out no one wanted him anyway, ’cept that groupa pissheads when a man did less of that now. Dunno why. (Could be I’m Jake The Muss Be Getting Older now) He couldn’t even smile, let alone burst out in his characteristic laughter at his own witty play on his once famous nickname. Yeah. I’m Once Was Jake. And he walked out into the kitchen to make some breakfast, got stopped at the sight of the fucken mess it was in, forgot about

heating

up the pot of pork bones and watercress and spuds, as he looked around for Cody. (Little cunt. I’ll wring his fucken neck. I’ve told him about leaving this mess, him and his mates.) That was it: no more fucken parties in this house. Hold it: a man is at these parties more than he’s not. Alright, they got to clean up after a party then, that’d be the rule. (And let one of them punks try and argue with me.)

Into the sitting room, the teevee in the corner there, the vase he’d bought with the cupla couches he’d picked up from Albie’s Second-Hand Furniture, and lied to everyone ole Albie’d thrown it in when he bought the couches, a fucken flour-er vase, when it was him (me) secretly wanting (just the once) to put flowers in it to see what other people, more real people, saw in them, but he couldn’t. For starters, just the picture of himself coming out of a shop, then getting the bus home carrying flowers was enough to put him off, and everytime he promised to do it when he was part drunk he just never got around to it and so the blue vase (come to think of it, it was one of the colours of the rocks in this morning’s dream) just sat

on the window-sill so the neighbours, if they were that interested which he doubted, or not in the permanently E for empty flower vase, could see the shape of it as part of their view of that corner of Jake and Cody’s rented State house in suburban Two Lakes where they swept the people who didn’t count and sent out the cops to collect a few, like society’s toll every week, all year every year, and trialled them, fined them, jailed some, weekend

community-worked

some, and generally let them, the scumbags, know that even their disorder, their own little sub-society structureless chaos was punishable. To let the town’s nobodies know there was a greater order and, Jake suspected, one which didn’t really want his sub-society to change, not for the better, since they made not just a living, but status (somehow—Jake couldn’t figure how the process went, of a lawyer defending a gang member arsehole and the gangie getting jail like Jimmy Bad Horse did, that cunt, and the lawyer got paid twice, once in money and the second in status).

The vase which he still promised to fill, the teevee, the shiny material couches everyone called babyshit brown and had holes worn through the material, a coffee table that’d never seen a cup of coffee (who drank coffee around here?) and that was it: Jake Heke’s total sitting-room furnishings.

In the old days a man and his flatmate Cody had extra — free — seats when the beer came in the dozen bottle crates but

everyone

drank the cans now, only old-fashion ones stuck with the big quart bottles or the flagons, but they were plastic now not glass you woke up to broken on the floor, or with lipstick marks from some bitch drinking straight from it, a half-gallon jar, or grease from someone’s lips after he’d had a feed and carried on drinking. Things’d changed, so weren’t no wooden beer-crate seats, so no splinters of wood if there’d been a fight, and even that was less these days, only if an old crew got together and lived the past, these people carried their grudges and old bitter memories like they carried their sideburns and sang old party songs even Jake’d got sick of, now this place a reminder from them days, a fucken mess, except say one thing for Cody and the crowd he got round with, they didn’t fight much, though he remembered the time when one of Cody’s mates pissed in the vase and Jake grabbed the cunt and marched him outside and tipped his piss over his head, treating his

vase like that, and then he turned around to see the whole fucken lot of them standing there, ’cept Cody, and they toldim leave their friend alone, Jake you done enough, he’s drunk he didn’t know what he was doing so don’t be hitting him. It wasn’t their numbers so much’d frightened him, as the intensity of their loyalty to their buddy and proved by the fact they were ready to confront him (me. Jake The Muss). He was only gonna give the fulla one crack anyrate and, besides, a vase full of his own piss all over him wouldn’ta been so hot, so to keep his pride Jake told the group, Anyone so much as touches that vase he gets it.