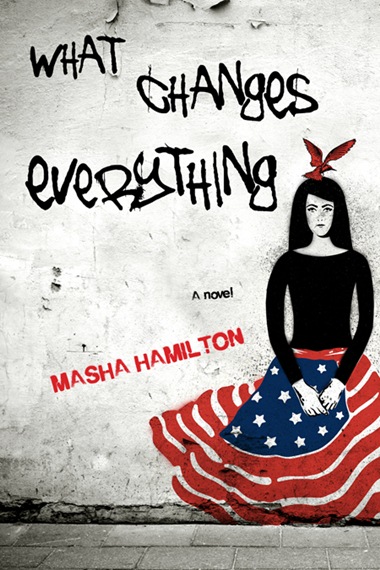

What Changes Everything

Read What Changes Everything Online

Authors: Masha Hamilton

ARC COPY ONLY - NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION

What Changes Everything

---

a l s o b y

M a s h a H a m i l t o n

31 Hours

The Camel Bookmobile

The Distance Between Us

Staircase of a Thousand Steps

The Distance Between Us

Staircase of a Thousand Steps

---

This is a work of fiction. The names, characters, places and incidents are either the>product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Unbridled Books

Copyright © 2013 by Masha Hamilton

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced

in any form without permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data [TK]

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Book Design by SH • CV

First Printing

You don‟t need a war.

You don‟t need to go anywhere.

It‟s a myth: if you hurl

Yourself at chaos

Chaos will catch you.

—Eliza Griswold

Beirut. Baghdad. Sarajevo. Bethlehem. Kabul. Not of course here.

—Adrienne Rich

Najibullah: Letter to My Daughters I

September 3rd, 1996

Destiny is a saddled ass, my daughters; he goes where you lead him. But you must know

the rules to discern the path. First, give full trust to no one. The smiling horseman with whom

you bow for dawn prayers may seek to kill you by nightfall. Work in cooperation, of course—

what dust would rise from one rider alone? But do not let your lashes slip lazily to your cheeks

while the sun remains in the sky. Whatever Allah wills shall be. Nevertheless, tie your steed‟s

knees tight before sleeping.

It is dawn just after prayers; Kabul‟s golden light creeps in through my window, a timid

but relentless thief here to steal the night, and I am imagining you three with me instead of in

Delhi, us all cross-legged on toshaks, look

ing directly into each other‟s faces. My mind has

become so practiced in seeing you where you are not, in fact, that I can almost hear you teasing

me now—Horsemen? Steeds? You would tell me, if you could, that these are male metaphors,

and male concerns.

But you‟ve been raised liberated girls; your dealings will be with both genders. Besides,

though perhaps it is less likely, a woman too may pat your back with a blade in her palm.

I have barely slept the night thinking of you girls and your mother. As reports reach me

of the fundamentalists clawing daily closer to Kabul, the courage that buffered me as

Afghanistan‟s president bolsters me still. I believe these extremists, being fellow Pashtuns, will at

last send me into exile, which means I will rejoin my family.

Nevertheless, as

it is hard to predict where a worn fighter‟s bullet will land

, there is

urgency to my task. For over four years and four months, I have been unable to share a meal

with you, hear in person of your plans or tell of mine. We have not played a single game of ping

pong nor watched a movie together. When I think of it, as is often, my eyes feel rubbed with salt,

my throat thickened with mud, my chest pummeled by an angry fist. I put these lessons in writing

to be sure you will have them in case you need them before we are reunited.

So then, the rules. When you must trust someone, rely on a stranger more easily than a

friend; yes, because a friend knows your soft spots. But remember family is the marrow of your

bones. Who is here with me s

till? My two UN "guards," and a young Pashtun, Amin, who waits

on me. But my daily companion, the one with whom I share my deepest thoughts, is my brother

Shahpur, your kaakaa jan. Together we follow politics and watch television and talk of you.

Shahpur celebrated—

but that‟s not the right word without you—

he marked my 49th birthday last

month, a hard day to be apart from my beloved wife and girls. He holds me upright in your

absence. You sisters, too, will lift each other when the need appears.

Take care of your mother-flower until I return to you. I became her tutor all those years

ago driven by the hope that she would fall in love with me over formulas and test questions. They

can arrest or exile me—I will always be a lucky man because of her. She gave me you three, and

a home of laughter even in dark times, and the strong foundation that has allowed me to do my

work.

And this rule: love your country. Victim of many men‟s fury, corrupted by fanatics who

believe our landlocked status means we sit in the c

up of their hands, it still remains proud. "I

come to you and my heart finds rest," Ahmed Shah Baba wrote of our motherland. "Away from

you, grief clings to my heart like a snake." I know your memories of Afghanistan will be tinged

by our separation and my detention. But put that aside, learn our history, and return one day to

make your own impact.

Remember that Afghanistan must be one united nation, all ethnic divisions discarded.

Remember the couplet of the great Pashtun poet and warrior Khushal Khan Khat

tak: "Sail

through vast oceans as long as you can, oh whale, for in small brooks I can predict your decay!"

Remember, also, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. He too endured house arrest. He too knew it

possible to be a devout Muslim and still support a progressive society. His goal, to unite all, was

noble. Together one day, we‟ll visit his resting place in Jalalabad.

Be brave. Be proud.

Fear and shame are father and son, and you should feel neither. You will need courage to

meet detractors—the strong or outspoken always have those who would malign them. Still, we

Afghans are raised on bravery with our morning chai; I remind you that it runs easily through

our blood.

Be punctual. Work hard. Memorize the

Quran. Don‟t forget your Dari. Never

boast: it is

the small mouth that speaks big words.

Do not believe the stories you hear about me, my daughters. At least, not wholly. You are

still so young—Muski only eight years old—but I know grim murmurs make their way to your

ears already; your mother tells me. If I was a puppet, how did I manage to hold on to power for

three years after the Soviets scuttled away? If I drew blood, it was only in self-defense or for

Afghanistan. If it was me who was the roadblock to peace, then why has our city been defaced by

warfare in the months and years since I left office? Do you remember Kharabat Street, its

musicians flinging open their doors to compete for the chance of performing at the palace, their

heart

thumping music expanding and floating into the mountains? Massoud‟s single

note rockets

left the Street of the Musicians in rubble. Districts where you three and your mother used to walk

are now impassible, proof enough that I preserved peace, not obstructed it.

And now your uncle is at my door. I will write you again soon—not a diary, since when

the days are filled with events that might make an interesting diary there is not a spare moment

to record them, and those are not my circumstances now. Instead, my enemies have given me the

gift of time. As a satellite phone is available too infrequently for my wishes, I will make for you a

written record of the state of your father‟s mind during this fifth year living as "Honored

Guest," while our fractious country and its devious leaders struggle forward without my firm

hand. I will ask the boy Amin to send these off discreetly, since I want no UN censor marring my

pages.

Soon, inshallah, I will rejoin you. Until then, with love for you, and a country of kisses for

your mother, my dearest Fati,

Najib

Amin, Sept. 3rd

Amin spread his rug on the ground behind the office and then parted his lips to inhale fully. A crippled sparrow stood in stingy bush-shade and watched. Smoke and exhaust threaded through Kabul‟s air, and the city‟s tensions pressed against the compound walls; nevertheless, nothing matched performing s

alat

under an open sky, even if sometimes the closeness to Allah made him feel that much more ashamed. He raised his hands next to his ears, crossed his arms, paused and then bent at the waist; he straightened, he bowed, he lowered his forehead to the earth in a dance of sacred ritual by now burrowed deep in muscle memory. He had first prayed as a child aside his father, mimicking the traditional movements in time to words of supplication. These days his own son often stood next to him, and so at its best, prayer connected him not only to his God, but to his past, his future, his people.

alat

under an open sky, even if sometimes the closeness to Allah made him feel that much more ashamed. He raised his hands next to his ears, crossed his arms, paused and then bent at the waist; he straightened, he bowed, he lowered his forehead to the earth in a dance of sacred ritual by now burrowed deep in muscle memory. He had first prayed as a child aside his father, mimicking the traditional movements in time to words of supplication. These days his own son often stood next to him, and so at its best, prayer connected him not only to his God, but to his past, his future, his people.

At its best. When he wasn‟t preoccupied, that is. September was his month of regret, the month when his mind willfully wandered.

As the sparrow hopped closer, he took measure of his regret; he found it hadn‟t shrunk over the last year, even though he‟d been a good man, or tried. Goodness wasn‟t simply a matter of intention; life conspired to sidetrack the well-meaning, and somehow doing right by those you loved most always proved far more complicated than being kind to strangers—as if the two, love and complications, had to be ingested in equal measure. He had long ago realized that the unintended sins of the virtuous caused the worst damage: sins committed when one should have known better, or tried harder, or spoken up or stayed silent.

"They will never know how fiercely I wish I could stand before them—before y

ou—an

d ask forgiveness." Amin could have said those words, though they belonged to Najib. Even in the middle of it, Amin had known it as an exceptional moment in his life. What he couldn‟t see then was what it would cost him. He‟d been so young. He‟d do it differently now, of course. Another chance was not to be had.

ou—an

d ask forgiveness." Amin could have said those words, though they belonged to Najib. Even in the middle of it, Amin had known it as an exceptional moment in his life. What he couldn‟t see then was what it would cost him. He‟d been so young. He‟d do it differently now, of course. Another chance was not to be had.

Nor another chance at this day‟s noon prayers. Najib, he could consider later. Lowering his forehead again to the prayer rug, he wordlessly asked Allah‟s forgiveness for his break in attention, cleared his mind and offered praise for the Master of the Judgment Day, the Powerful One of ninety-nine names.

Clarissa, September 3rd

Clarissa pressed the "end" button on the phone‟s receiver. Its quiet click made her think of everyday conclusions: a door closing, a bridge rising, the halting of a heart. She saw out the window that night had choked off the Brooklyn sky while she‟d been talking to her husband half a world away. Her

new h

usband, as she still thought of him—though they‟d been married almost three years, husband was not a word that fell easily from her lips.

new h

usband, as she still thought of him—though they‟d been married almost three years, husband was not a word that fell easily from her lips.

She didn‟t want to feel irritated with him. She dropped her tensed shoulders and shook her hands as if to release the memory of long miles, missed connections, censored language. She never liked to argue long-distance—not with a friend, not with her brother, certainly not with this man she'd married. Robbed of touch or expression, words became easily knotted.

Besides, life should not be disrupted so near to sleep. Leave it for another day. She was 42; she knew how to compartmentalize by this time, didn‟t she?

Urban gray lay beyond the window, with shadows and sirens and complicated nighttime intentions. She turned back toward the humdrum solidity of the lit kitchen: a table messy with notes for her study on the urban history of Detroit, yogurt, cranberry juice and spinach in the fridge, a bottle of calcium pills on the counter next to a scrawled note from her step-daughter to her husband, weeks old now. A coffee machine still partly filled with day-old brew, a radio quietly broadcasting unalarming news. She welcomed these particulars that were the bones of her current life, but she did not pause to treasure them. There it is, then, the human tragedy: failure to celebrate the plain pillow that catches one‟s head each night.

Other books

Viking's Orders by Marsh, Anne

Afloat and Ashore by James Fenimore Cooper

Special Needs by K.A. Merikan

Young Petrella by Michael Gilbert

Eli the Good by Silas House

Unraveled by Jennifer Estep

The Eve Genome by Joanne Brothwell

The Problem with Promises by Leigh Evans

Only In Dreams (Stubborn Love Series) by Owens, Wendy

A Child of the Cloth by James E. Probetts