What Hath God Wrought (118 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

Counting Texas, Oregon, and the Mexico Cession, Polk acquired more territory for the United States than any other president;

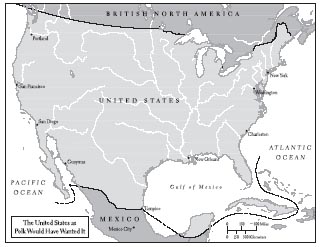

This map reflects the boundary Polk wanted the peace treaty with Mexico to specify, as well as his attempts to purchase Cuba from Spain and invade Yucatan after the war was over. Other U.S. imperialists wanted to take over all of Mexico, as well as what is now British Columbia.

On February 2, 1848, the peace commissioners signed their document “In the Name of Almighty God” at Guadalupe Hidalgo, site of Mexico’s national shrine to the Blessed Virgin Mary, which Trist chose as a location to impress the Mexican public with the treaty’s authority.

29

Polk’s order to General Butler to terminate the negotiations forcibly arrived too late to prevent the signing. Later the American diplomat revealed to his wife what had been his guiding principles.

My object, through out was,

not

to obtain all I could, but on the contrary to make the treaty as little exacting as possible from Mexico, as was compatible with its being accepted at home. In this I was governed by two considerations: one was the iniquity of the war, as an abuse of power on our part; the other was that the more disadvantageous the treaty was made to Mexico, the stronger would be the ground of opposition to it in the Mexican Congress.

Trist wanted a treaty that could realistically end the war, capable of ratification by both sides and avoiding such outcomes as the conquest of All Mexico, that country’s complete dismemberment, or the indefinite prolongation of anarchy and fighting. Privately, he also felt “shame” at his country’s conduct in the war. “For though it would not have done for me to say so

there

, that was a thing for every right-minded American to be ashamed of,” he remembered thinking.

30

His recognition of a moral standard higher than the unbridled pursuit of national interest was no doubt unusual in the history of diplomacy.

Trist achieved his treaty at considerable personal cost, it turned out. On January 15, 1848, President Polk received his commissioner’s message of December 6. He termed it “insulting and contemptably [

sic

] base,” its author “destitute of honour or principle.” He hoped to punish the disobedient diplomat “severely.” Polk laid much of the blame on Scott, whom he suspected (correctly, in fact) of having encouraged Trist in his course. Collaboration between Scott and Trist proved even more infuriating to Polk than had conflict between them.

31

When Trist evinced a determination to remain in Mexico long enough to testify on Scott’s behalf before the court of inquiry, Scott’s successor General Butler, following the president’s orders, arrested the former peace commissioner and sent him back to the United States in custody. There he was neither indicted nor rewarded for his great achievement. Trist lived out the rest of his life in obscurity and modest financial circumstances; in 1860 the Virginian voted for Lincoln and the following year opposed secession. The Polk administration had cut off his salary and expense allowance effective November 6, 1847, the date Trist received his dismissal. Not until 1871 did Congress pass an act paying him (with interest) for the period when he negotiated the historic treaty; it did so at the behest of another statesman of conscience, Senator Charles Sumner.

32

Trist dispatched his new treaty back to Washington with a friend, James Freaner, a reporter for the

New Orleans Delta

. Avoiding the telegraph for security reasons, this private courier made the trip in only seventeen days. (As he had promised to do, Freaner dropped off a personal letter from Nicholas to Virginia Trist before delivering the treaty to the secretary of state.)

33

Meanwhile, Scott had agreed with the Mexicans to an armistice while the two governments pondered ratification. Despite Polk’s bitterness toward Trist, the president saw at once that he had no realistic alternative to submitting the treaty for the Senate’s consent. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee at first called the treaty a nullity because Trist possessed no authority to make it, and urged appointment of a new commissioner to draw up another. But Polk realized that delay would play into the hands of his Whig opponents and those of the intransigent

puros

in Mexico. The House would probably vote no more supplies for war, and the United States might even end up able to secure less territory than Trist had obtained. And, after all, the treaty gave him everything from Mexico that he had originally desired.

34

The president persuaded the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to report the treaty, even with no recommendation.

When the treaty reached the Senate floor, two challenges confronted it. From the Whig side came a proposal to make peace with no territorial acquisitions at all except the port of San Francisco, which Daniel Webster had coveted when he was secretary of state. The New England whaling fleet (whose shipowners were Whigs) could use the harbor. Mexico had expressed willingness to sell that part of Alta California to the United States as early as the first round of negotiations in September 1847. Eighteen of the twenty-one Senate Whigs voted for such a peace, but that was not enough. From the opposite side of the opinion spectrum, Jefferson Davis’s resolution to require more extensive territorial acquisitions than Trist had secured received only eleven votes. On March 10, 1848, the Senate voted to ratify the treaty: 38 in favor, 14 opposed, with 4 abstentions. Those voting no included seven Whigs, among them Webster, whose youngest son, Edward, had died of typhoid fever on duty in Mexico ten days before the treaty was signed. The seven Democrats voting no included Benton, angry at (among other things) the administration’s treatment of his son-in-law Frémont. Those voting for ratification included fourteen Whigs, whose desire for peace, in the final analysis, trumped their preference for No Territory.

35

Horace Greeley’s strongly antiwar Whig

New York Tribune

commented resignedly, “Let us have peace, no matter if the adjuncts are revolting.” On the Democratic side, the papers that had trumpeted the cause of All Mexico generally accepted the end of their dream with surprisingly little complaint. Only the

New York Sun

protested strongly, calling Trist’s treaty “an act of treason to the integrity, position, and honor of this Empire.”

36

The speed with which most of the penny press abandoned the cause of All Mexico suggests that it may have been more an early example of sensationalism selling newspapers than a serious policy proposal.

Ratification by the two houses of the Mexican Congress was complicated by the fact that the U.S. Senate had amended the treaty to remove certain guarantees for the Roman Catholic Church and the recipients of Mexican land grants. Future Mexican president Benito Juárez, among other

puros

, argued that Mexico did not need to sign a disadvantageous peace and could prevail by waging a guerrilla war in which the invaders would inevitably tire and go home. Nevertheless, the opposition to the treaty was overcome and the ratifications exchanged on May 30. The same day José Herrera, the moderate

federalista

who had tried to avoid war with the United States, returned to the presidency of Mexico. The evacuation of the occupying army began, and on June 12 the Mexican Tricolor replaced the Stars and Stripes over the Zócalo.

37

Historians have overwhelmingly concluded that Trist made a courageous and justified decision in defying his orders and remaining to secure a peace treaty. Even Justin Smith, Polk’s strongest defender among historians, called Trist’s decision the right one, and “a truly noble act.”

38

There is a strong parallel (though one not often remarked) between Polk’s resolution of the Oregon Question and that of the U.S.-Mexican War. In both cases the president made extravagant demands but unhesitatingly accepted a realistic and advantageous solution when offered it. In the case of Oregon, he probably had planned the outcome all along; probably not in the case of Mexico. Yet it is interesting that Polk waited twelve days after receiving news of Trist’s defiance before sending an order off to Mexico to abort whatever negotiations he might have under way. Perhaps the president secretly felt willing to give Trist a chance, provided the administration did not bear responsibility for the negotiations.

39

Indeed, Polk had earlier confided to his diary the thought that he would not mind if Moses Beach exceeded his instructions and obtained a peace treaty. “Should he do so, and it is a good one, I will waive his authority to make it, and submit it to the Senate.”

40

Even though the treaty represented the work of a man who defied him, it embodied the objectives for which Polk had gone to war. Polk had successfully discovered the latent constitutional powers of the commander in chief to provoke a war, secure congressional support for it, shape the strategy for fighting it, appoint generals, and define the terms of peace. He probably did as much as anyone to expand the powers of the presidency—certainly at least as much as Jackson, who is more remembered for doing it. The contrast with Madison’s conduct of the War of 1812 could not be sharper. Wartime presidents since Polk, including Lincoln, Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, and Lyndon Johnson, have followed in Polk’s footsteps.

Counting Texas, Oregon, California, and New Mexico, James K. Polk extended the domain of the United States more than any other president, even Thomas Jefferson or Andrew Johnson (who acquired Alaska). His war against Mexico did more to define the nation’s continental scope than any conflict since the Seven Years War eliminated French power between the Appalachians and the Mississippi. On July 6, 1848, the president sent a message to Congress pointing with pride to the acquisition of California and New Mexico and declaring that, although they had remained “of little value” in Mexican hands, “as a part of our Union they will be productive of vast benefits to the United States, to the commercial world, and the general interests of mankind.”

41

Polk conceived of the Pacific Coast empire he had achieved not as an escape into a romanticized Arcadia of subsistence family farms, but as an opening for American enterprise into new avenues of “the commercial world.” For all his supporters’ talk of manifest destiny, Polk had not trusted in an inevitable destiny to expand westward, but, anxious about national security and the danger of British preemption in particular, and prompted by the conviction that the American political, social, and economic order required continual room for physical expansion, he had hastily confronted both the Oregon and Mexican controversies head-on. Certain that American strength served “the general interests of mankind,” he had not hesitated to adopt a bellicose tone and make extreme demands. His high-risk strategy had worked in the end because the British proved reasonable, the Mexicans disunited and bankrupt, the U.S. armed forces superbly effective, and Nicholas Trist a wise if disobedient diplomat. In each case, Polk himself knew just when to abandon truculence and settle.

In the same statement to Congress, the president described California and New Mexico as “almost unoccupied.” But the people affected most immediately by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were the residents of the domain Mexico relinquished, including some ninety thousand Hispanics and a considerably larger number of tribal Indians. By the Mexican Constitution of 1824, once again legally in force in 1848, all these persons, including the Indians, had been Mexican citizens. According to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo they were to become United States citizens unless they took action to retain their Mexican citizenship. Despite the treaty’s assurances, however, the Mexican Americans found themselves generally treated like foreigners in the country where their people had lived for generations. Some individuals remained prominent under the new regime; Mariano Vallejo participated in the California state constitutional convention and became a senator in the state legislature, though he lost most of his extensive landholdings. Vallejo’s property losses were typical of the fate of most Mexican Americans, unfamiliar as they were with the English language or Anglo-American land law, and surrounded by newcomers eager to take advantage of them and obtain title to their holdings by fair means or foul. The state of California placed heavy burdens of legal proof on the owners of Mexican land grants to validate their titles, in violation of the spirit if not the letter of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Although state and federal courts heard many cases arising out of the treaty in decades to come, they did not consistently defend the rights of preexisting property owners as its provisions seemed to require. California did not recognize Mexican Americans as citizens until a decision by the state supreme court in 1870. In New Mexico the Hispanic population did not receive their promised full rights of citizenship until after statehood in 1912. Texas restricted the right to own land to persons of the white race, and Mexican Americans had difficulty establishing themselves as legally white. In some regions of eastern Texas, Mexican Americans were forcibly expelled.

42