What Hath God Wrought (115 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

Eager to move most of his army inland before the yellow fever descended, Scott arranged to govern Veracruz with a skeleton force. This necessitated conciliating the local population. Unlike Taylor, Scott insisted on strict control of his occupying troops and allowed no outrages to be perpetrated on civilians. He paid for supplies his soldiers needed, instead of just commandeering them as the Polk administration had told him to do in order to save money. He reopened the port to the commerce of the world, so normal business activity could resume, but with U.S. officials collecting the customary tariff duties. And he stationed a guard by every Catholic church to protect it and its worshippers. All this happened not a moment too soon: On April 9, two deaths from yellow fever were reported.

88

Why had Mexico’s most important port and the gateway to the nation’s heartland been so weakly defended? Why was there no attempt to relieve the siege of Veracruz? A revolt had broken out in Mexico City against the government. As divided as people were in the United States over political partisanship, section, and the wisdom of the war, the Mexican public was even more disunited—by region, class, and ideology. When Santa Anna went off to lead the army against Taylor, he left his vice president, Valentín Gómez Farías, in Mexico City as acting president. Gómez Farías was a

federalista puro

, prowar and anticlerical. He had been instrumental in secularizing the California missions back in 1833, and this time he had another program to seize church property for the benefit of the state. Faced with a desperate shortage of money to wage war, on January 11, 1847, Gómez Farías signed a law requisitioning 15 million pesos (a peso being worth about the same as a U.S. dollar) from the Roman Catholic Church. The church, which as Mexico’s largest institutional investor often acted like a bank, had loaned money to the government in the past but was not disposed to accept confiscation of about 10 percent of its assets.

89

Ecclesiastical authorities in the capital secretly funded an uprising against the government by some upper-middle-class, proclerical national guard units stationed in Mexico City. The revolt also received encouragement from Moses Beach and Jane Storm of the

New York Sun

, ostensibly in the city on business. (Civilians traveled surprisingly freely in the nineteenth century, even between countries at war with each other.) Actually the two were on a secret mission for the U.S. government, hoping to overthrow the Mexican government and install one that would make peace.

90

Although the church commanded widespread loyalty and sympathy, the rebellion proved highly unpopular, interfering as it did with the defense of the country against invasion. It got the derisive name “revolt of the

polkos

” from the polka dance then fashionable among the city’s elite. Despite being small in scope, the revolt of the

polkos

preoccupied the Mexican government, preventing aid to Veracruz. Santa Anna’s return to the capital on March 21 ended the revolt but at a cost. He turned his back on those who had elected him (as he had done in 1834), rescinded the requisition, fired Gómez Farías by abolishing the vice presidency, and settled for another loan of 1.5 million pesos from the church—a pittance in relation to the government’s wartime needs.

91

Scott advanced toward Mexico City via Jalapa and Puebla, following the same route that Hernán Cortez had taken 328 years earlier, as many noticed at the time. William Hickling Prescott’s vividly written

History of the Conquest of Mexico

(1843) constituted favorite reading among the intellectually inclined members of the U.S. Army (though Prescott, a New England Whig, deplored the current conquest of Mexico as “mad and unprincipled”). Promising the crowds to die fighting rather than let the enemy enter “the imperial capital of Azteca,” Santa Anna came out to meet Scott’s army on the border between the coastal plain and the high country, not far from his own estate, El Encero.

92

To oppose the invaders he gathered a force of about twelve thousand, half of them veterans of Buena Vista and the rest untrained raw recruits.

Cerro Gordo, also called Cerro Telégrafo (Signal Hill), a thousand feet high, dominated the road to Mexico City, and there Santa Anna concentrated his defense. Half a mile north of it lay another hill, La Atalaya (the Watchtower). Two Mexican engineering officers recommended placing artillery atop La Atalaya, but

el presidente

dismissed their advice, supposing that no one could get through the rough terrain and thick briars to approach from that direction.

93

In one of the most brilliant undertakings of his long and brilliant career, Robert E. Lee reconnoitered a trail that U.S. troops could cut through underbrush, bypassing the main highway where the Mexicans awaited them, and coming up on La Atalaya. At one point the daring scout had to lie motionless behind a log while Mexican soldiers sat on it and chatted only inches away. On April 17, 1847, Lee guided Twiggs’s division of regulars along the route he had traced. With La Atalaya only lightly defended, the Americans captured it and that night installed heavy guns, laboriously carried along Lee’s pathway, on the hilltop. At dawn the next day, this artillery supported an assault on Cerro Gordo itself, while other U.S. units struck the Mexican army at both front and rear. Santa Anna’s outmaneuvered forces fled, as did their commander, leaving behind a vast amount of equipment that included virtually all their artillery, twenty thousand pesos in coin intended to meet the army’s payroll, and an artificial leg Santa Anna wore to replace the one he had lost fighting the French. (Amused U.S. soldiers made up a parody of one of their favorite songs, “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” entitled “The Leg I Left Behind Me.”) Scott’s army took some four thousand Mexican prisoners—a thousand of whom promptly escaped in all the confusion. The general and his staff soon relaxed in Santa Anna’s hacienda, El Encero, where the perceptive Colonel Hitchcock noticed that all the

caudillo

’s art works were foreign; none of them showed “the genius of the Mexicans.”

94

By cold logic, the Battle of Cerro Gordo should have put an end to the Mexican war effort. That it did not was due less to the Mexican government and high command than to the stubborn determination of the people themselves not to accept defeat. Scott’s small army could only advance slowly, and in fact took four more months to reach the historic capital of Mexican civilization. When it occupied Puebla, the second largest city in the country and one that had been a center of opposition to Santa Anna, some of the church authorities cooperated with the invaders, but ordinary Mexicans who did so exposed themselves to ostracism or worse from their fellow citizens.

95

Scott waited in Puebla six weeks of the summer for reinforcements to replace the volunteers whose one-year enlistments expired. Only 10 percent of those whose time was up chose to reenlist. The mood of the soldiers had become one of disenchantment as the grim reality of war sank in. Captain Kirby Smith of the Regular Army wrote home to his wife about his change of attitude since the war began. “How differently I feel now with regard to the war from what I did then!

Then

vague visions of glory and a speedy peace floated through my brain.” Now he felt only gloomy foreboding. “Alas, the chance is I shall never see you again!” Captain Smith would fall mortally wounded on September 8, before word of his promotion to lieutenant colonel reached him.

96

Guerrilla actions along Scott’s exposed supply line, made all the more tenuous by a shortage of transport, eventually prompted the U.S. general to cut himself off from his base of operations and live off the country when he resumed his advance—an example that stuck in the mind of Lieutenant Grant, who would do the same in his campaign against Vicksburg in 1863. Grant also remembered the valor of his Mexican adversaries, even in their defeat: “I have seen as brave stands made by some of these men as I have ever seen made by soldiers,” he wrote in his

Memoirs

.

97

In June, Santa Anna hinted, through a message sent via the British, that he might make peace in return for a million-dollar bribe, with ten thousand up front. Scott and the State Department representative Nicholas Trist, who was authorized to negotiate with the Mexicans, after hesitation and discussion with the other American generals, decided to send the ten thousand. The money disappeared to no discernible purpose. Santa Anna may well have been prepared to sell out his country’s interests; the Mexican Congress suspected it, and had passed a law on April 20 making unauthorized peace negotiations treason. Scott’s willingness to pursue any avenue for peace, after it became known to the U.S. public and administration (probably revealed by Gideon Pillow), would come back to haunt him.

98

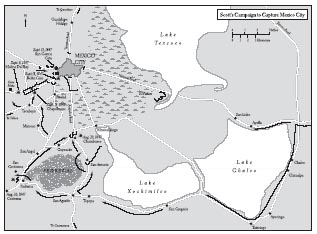

It took all Scott’s military genius and much hard fighting by his army before the Americans reached the goal of their campaign. On August 7, 1847, 10,738 of them set out through mountain passes ten thousand feet high, undertaking to capture a metropolis of two hundred thousand people. The City of Mexico, located in the Valley of Mexico, occupied an island in the midst of marshland, approachable only along certain causeways. Santa Anna had recovered, phoenix-like, from the disgrace of defeat at Cerro Gordo and commanded the defense of his capital. Once again gathering troops and equipment, he had managed to get around the naval blockade by importing weapons through Guatemala.

99

This consummate salesman was always better at raising armies than at keeping or using them. Santa Anna assumed Scott would advance by the most direct route and constructed fortifications accordingly. But U.S. engineer officers—notably Colonel James Duncan and, once again, Captain Robert E. Lee—identified other routes, and Scott took his army via the south, a force guided by Lee even crossing the rugged bed of dried lava called the Pedregal. At Contreras on August 20, Scott’s army overcame that of General Gabriel Valencia as a result of jealousy between the Mexican generals; Valencia disobeyed Santa Anna’s orders in hopes of getting credit for a victory himself, whereupon Santa Anna refused to reinforce Valencia. To cover his withdrawal following the battle, Santa Anna placed some fifteen hundred local national guardsmen and

sanpatricios

in the Franciscan monastery of San Mateo, protecting a bridge over the Río Churubusco (named, appropriately, for the Aztec god of war). Scott, hoping to smash the retreating Mexicans as they crossed the Churubusco, ordered the monastery taken. What followed was one of the toughest fights of the war, a demonstration of heroism by common soldiers on both sides. Time and again the attackers charged through cornfields to be repulsed by the dogged defenders. Only after the militia had run out of ammunition were the Mexicans overcome; Santa Anna refused their pleas for resupply, having erroneously written off their case as hopeless and merely a means to buy time. The

sanpatricios

fought with a courage born of desperation, knowing the likely fate that awaited them as prisoners. In the end eighty-five of them fell into the hands of their former comrades; about sixty-five had died in the battle, and a hundred or more escaped.

100

At this point Scott could have entered Mexico City. He chose not to, believing that his hungry troops, temporarily disorganized by battle, would pillage and burn. In such a state of disorder, he explained to the secretary of war, all Mexican government might dissolve, leaving no one with whom he could make a treaty.

101

Scott’s objective was not to create an urban wasteland but to “conquer a peace” (in the phrase of the time), so he halted at the city gates and offered to negotiate. Secret messages had once again given Scott reason to hope that the unpredictable Santa Anna would come to terms. A truce commenced on August 21, but the talks it permitted led nowhere, since the Mexicans proved unwilling to cede as much territory as the U.S. negotiators demanded. Meanwhile, Santa Anna strengthened his defenses, and Scott purchased provisions from his enemies. (Rather than buy still more, he turned loose some three thousand Mexican prisoners.) By September 6, the two sides felt ready to resume the war. Santa Anna called upon the city’s people to “preserve your altars from infamous violation, and your daughters and your wives from the extremity of insult.”

102

Intelligence reports reached Scott that the Mexicans were re-casting church bells into cannons at a flour mill called Molino del Rey. The general ordered a quick raid on the mill conducted in the early morning of September 8. Unfortunately Santa Anna’s own intelligence warned him in time to prepare a warm reception for the attackers, and the engagement turned into a major battle. Before the Americans succeeded in destroying the site, they suffered almost eight hundred casualties, fully a quarter of their troops engaged, making it a Pyrrhic victory for an army that had only about eight thousand effectives now available for advance into the enemy capital. Worse, the intelligence on which the attack was based turned out to be faulty: The Molino contained no weapons of mass destruction.