What If? (10 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

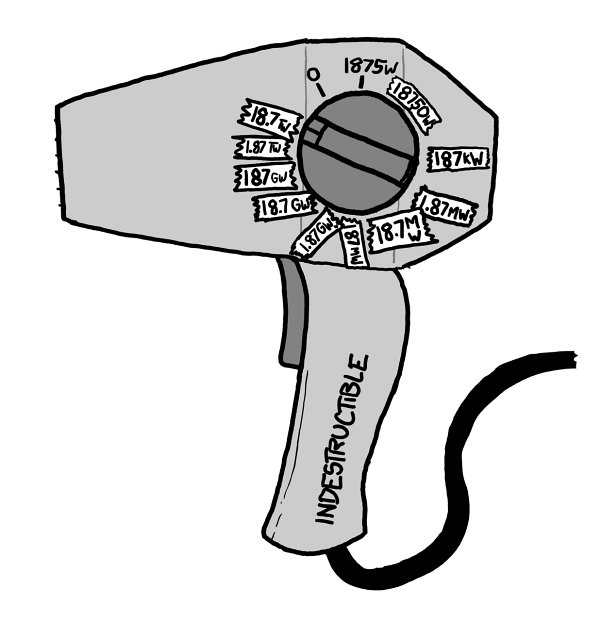

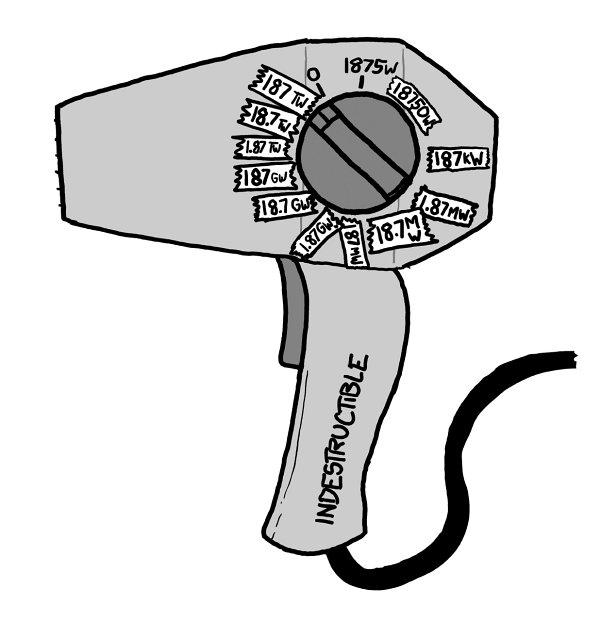

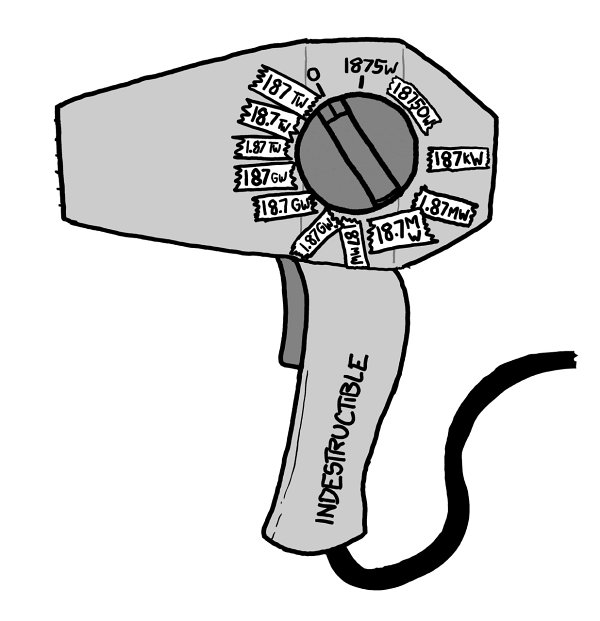

We’re at 1.875 gigawatts (I lied about stopping). According to

Back to the Future,

the hair dryer is now drawing enough power to travel back in time.

Th

e box is blindingly bright, and you can’t get closer than a few hundred meters due to the intense heat. It sits in the middle of a growing pool of lava. Anything within 50–100 meters bursts into flame. A column of heat and smoke rise high into the air. Periodic explosions of gas beneath the box launch it into the air, and it starts fires and forms a new lava pool where it lands.

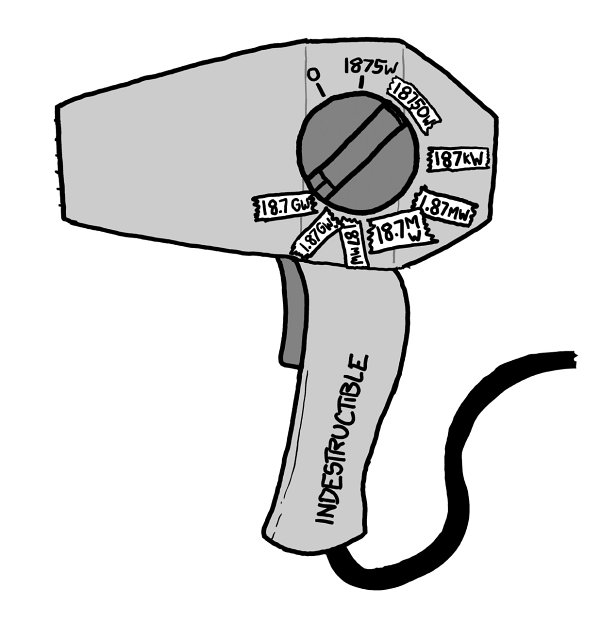

We keep turning the dial.

At 18.7 gigawatts, the conditions around the box are similar to those on the pad during a space shuttle launch.

Th

e box begins to be tossed around by the powerful updrafts it’s creating.

In 1914, H. G. Wells imagined devices like this in his book

Th

e World Set Free

. He wrote of a type of bomb that, instead of exploding once, exploded

continuously,

a slow-burn inferno that

started inextinguishable fires in the hearts of cities.

Th

e story eerily foreshadowed the development, 30 years later, of nuclear weapons.

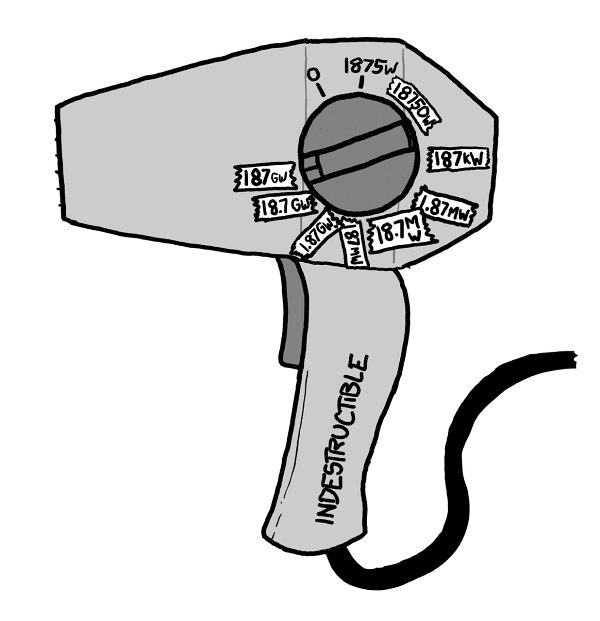

Th

e box is now soaring through the air. Each time it nears the ground, it superheats the surface, and the plume of expanding air hurls it back into the sky.

Th

e outpouring of 1.875 terawatts is like a house-sized stack of TNT going off

every second.

A trail of firestorms

—

massive conflagrations that sustain themselves by creating their own wind systems

—

winds its way across the landscape.

A new milestone:

Th

e hair dryer is now, impossibly, consuming more power than every other electrical device on the planet combined.

Th

e box, soaring high above the surface, is putting out energy equivalent to three Trinity tests every

second.

At this point, the pattern is obvious.

Th

is thing is going to skip around the atmosphere until it destroys the planet.

Let’s try something different.

We turn the dial to zero as the box is passing over northern Canada. Rapidly cooling, it plummets to Earth, landing in Great Bear Lake with a plume of steam.

And then . . .

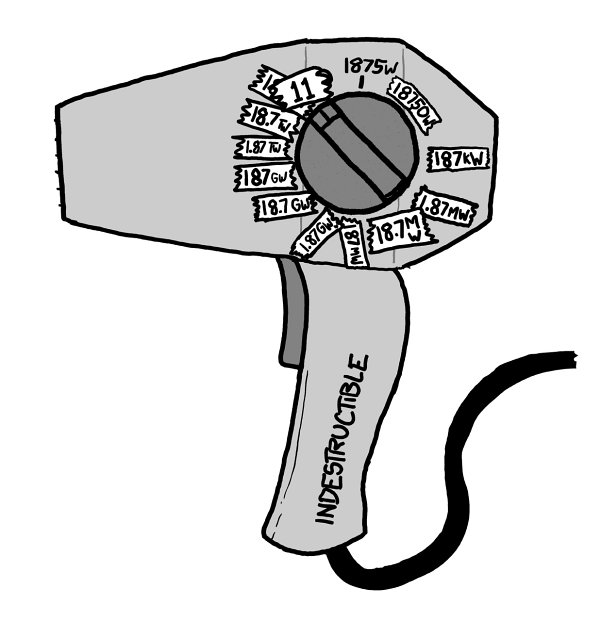

In this case, that’s 11 petawatts.

A brief story:

Th

e official record for the fastest manmade object is the Helios 2 probe, which reached about 70 km/s in a close swing around the Sun. But it’s possible the actual holder of that title is a two-ton metal manhole cover.

Th

e cover sat atop a shaft at an underground nuclear test site operated by Los Alamos as part of Operation

Plumbbob. When the 1-kiloton nuke went off below, the facility effectively became a nuclear potato cannon, giving the cap a gigantic kick. A high-speed camera trained on the lid caught only one frame of it moving upward before it vanished

—

which means it was moving at a minimum of 66 km/s.

Th

e cap was never found.

Now, 66 km/s is about six times escape velocity, but contrary to common speculation,

it’s unlikely the cap ever reached space. Newton’s impact depth approximation suggests that it was either destroyed completely by impact with the air or slowed and fell back to Earth.

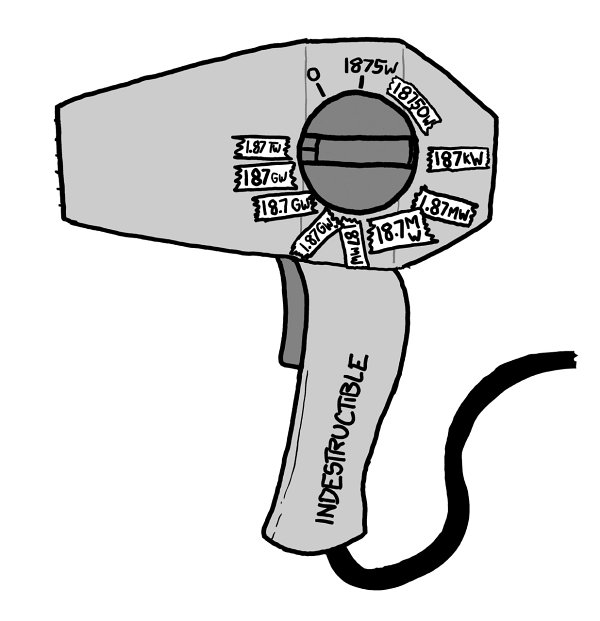

When we turn it back on, our reactivated hair dryer box, bobbing in lake water, undergoes a similar process.

Th

e heated steam below it expands outward, and as the box rises into the air, the entire surface of

the lake turns to steam.

Th

e steam, heated to a plasma by the flood of radiation, accelerates the box faster and faster.

Photo courtesy of Commander Hadfield

Rather than slam into the atmosphere like the manhole cover, the box flies through a bubble of expanding plasma that offers little resistance. It exits the atmosphere and continues away, slowly fading from second sun to dim star. Much of the Northwest Territories is burning, but the Earth has survived.

However, a few may wish we hadn’t.