What If Ireland Defaults? (12 page)

Read What If Ireland Defaults? Online

Authors: Brian Lucey

Ireland's Public Debt â Tell Me a Story We Have Not Heard Yet â¦

Seamus is a lecturer in the School of Economics in University College Cork.

There has been an ongoing, and at times confusing, debate about what Ireland's public debt will be in 2015. This chapter aims to look at some of the different elements of Irish public debt and the factors that can pull us away from the precipice of a sovereign default. This would be relatively straightforward if there was a universally accepted definition of public debt; there is not.

Economists are at heart storytellers. As storytellers, economists decide what matters for their purposes; they are, in a word, selective. By appreciating economists as storytellers, the general public can perhaps appreciate better why economists disagree. The spectre of default in Ireland is an exemplar of storytelling and how appreciating the choices the economist as storyteller makes is crucial in enabling the reader of such stories entering into that economist's imaginative world. So, let me tell you a story of default.

As a starting point we will use the general government debt (GGD) measure as defined in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. This is the measure used by Eurostat when compiling EU data and is also commonly used by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organisation of Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). The GGD is the consolidated gross total of all liabilities of general government.

In the GGD no allowance is made for any assets that may offset some of these liabilities. The GGD is simply the total of all general government liabilities. The Maastricht Treaty laid out the rules for entry and participation in the single currency. One of these was that the GGD could not exceed 60 per cent of a country's nominal gross domestic product (GDP). At the end of 2011 only four Eurozone countries satisfied this limit: Finland, Luxembourg, Slovakia and Slovenia. All other countries were in excess of the 60 per cent limit.

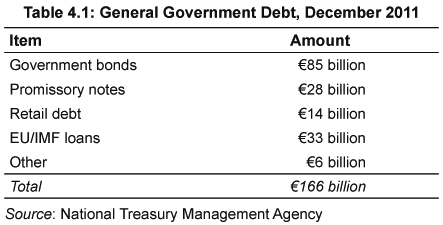

At the end of 2011, Ireland's GGD was â¬166 billion. The composition of this debt is shown in Table 4.1. Although we are still awaiting the final figure it is likely that 2011 nominal GDP will be around â¬155 billion. This means our debt to GDP ratio is probably 107 per cent.

It is also important to note that there was â¬13 billion of cash in the Exchequer Account at the end of 2011 which is not offset when determining the GGD.

Just as there is no single definition of public debt, there is no universally accepted threshold of where this debt becomes unsustainable with a default viewed as inevitable. The 60 per cent threshold was chosen for the Maastricht Treaty simply because this was viewed as a âsafe' level of public debt. At the time of the introduction of the Euro in 1999, original members of the Eurozone such as Belgium and Italy already had debt that was above 100 per cent of GDP.

Recent studies have shown that a public debt in excess of 80 per cent of GDP has a negative effect on economic growth, but this is not the same as saying the debt is unsustainable. In a European context it is likely that a debt ratio in excess of 120 per cent puts a country in grave danger of seeing its debt spiral out of control.

At the end of 2011 the Greek debt ratio was well in excess of this level at 160 per cent, with Italy right on threshold at 120 per cent. In 2011, Ireland, with a debt of 107 per cent of GDP, was below this threshold and while there are some (including me) who envisage the debt ratio stabilising and subsequently falling away from these levels, there are many who see the debt ratio breaking through this threshold and continuing to rise. In one view default can be avoided; in the other it is inevitable.

To see why the choice of these thresholds is not universal we simply have to look at the example of Japan. At the end of 2011, the Japanese GGD was 230 per cent of GDP. This is more than twice the Irish ratio but there is no one writing books stating that Japan is on the verge of default. At the end of 2011 the yield on ten-year Japanese government bonds was less than 1 per cent. Investors in Japanese bonds do not think they will default either.

There are a myriad of reasons as to why Japanese debt is sustainable at 230 per cent of GDP while default is the only outcome for Greece with a debt of 160 per cent of GDP. The key one is that the Japanese government controls the Bank of Japan, which can simply print more yen to repay their debts. Greece cannot avail of anything like this facility with the European Central Bank (ECB).

The debt ratio is a straightforward calculation that puts the total debt in the numerator and the level of GDP in the denominator. Changes in either will bring about changes in the ratio.

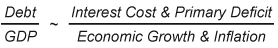

In order for the debt to be sustainable it is necessary that the average interest rate on the debt is less than the sum of the growth and inflation rates unless the government runs a sufficiently large primary surplus. The primary balance is the budget balance excluding interest payments. If a country is running a primary deficit and the interest rate is greater than the nominal growth rate the debt ratio will rise unsustainably.

At the time of the Budget in December 2011 the Department of Finance estimated that nominal growth in 2012 would be 2.3 per cent and that there would be a primary deficit in 2012 of 4.1 per cent of GDP. In both cases we miss the debt sustainability criteria. The interest rate on our debt is more than double the growth rate and there is no primary surplus to offset this interest cost. In 2012 the GGD is forecast to rise from 107 per cent to 114 per cent of GDP.

Over the coming years the nominal growth rate is forecast to rise to around 4 per cent a year, though changes to real growth or inflation will affect this. This will still be below the average interest rate on our debt, which is forecast to be 5.2 per cent in 2015, so in the absence of a sufficiently large primary surplus the debt ratio will continue to rise.

The primary balance is forecast to move from a deficit of 4 per cent of GDP in 2012 to a surplus of 3 per cent in 2015. It is this improvement in the public finances that will stabilise the debt ratio. If these conditions are satisfied in 2015 the debt will fall from 117 per cent to 114 per cent of GDP over the year.

This dynamic was improved considerably by the EU decision in July 2011 to reduce the interest rate on loans provided as part of the EU/IMF programme. This decision reduced the average interest rate on Irish debt by about 1 per cent and substantially increased the impact of a primary surplus on the debt ratio. If these interest rate reductions were not granted it is unlikely that the debt ratio would have been contained.

To see why this debt sustainability story is plausible we are going to do two things. First, we will explore how the GGD got to â¬166 billion by 2011; and second, what it will rise to by 2015.

At the end of 2007, Ireland's GGD was â¬47 billion. This is the debt level we brought into the crisis, which was largely a result of the previous crisis in the public finances in the 1980s. In general governments do not repay debt, rolling it over instead by borrowing anew. From 2007, the debt then increased by â¬119 billion in just four years.

From 2007 to 2009, the cash balances in the Exchequer and other accounts increased from just under â¬4 billion to almost â¬17 billion. During 2008 and 2009 the National Treasury Management Agency had the foresight to borrow funds on international markets to build up these cash balances before Ireland was shut out of the bond markets in late 2010. This increase in our cash buffer accounts for about â¬13 billion of the rise in the government debt.

Financing the services provided by government in these four years required â¬59 billion of borrowing. This was necessary to fill the gap that emerged between government revenue and government expenditure and to ensure that the government could meet its pay, pensions, social welfare and interest outgoings. Interest expenditure over the four years was â¬13 billion.

Separately, there is the money that has been used for the bailout of our delinquent banking system. By the end of 2010, the Exchequer had contributed around â¬9 billion directly to the banks. This was evenly split between borrowed money paid into the National Pension Reserve Fund since 2007 that was subsequently used as part of the initial recapitalisations of AIB and Bank of Ireland, and direct contributions from the Exchequer to Anglo, Irish National Building Society (INBS) and EBS.

There was also the creation of â¬31 billion of promissory notes given to Anglo, INBS and EBS in 2010. These are a promise by the state to pay this money to the banks, but the payment will be spread out over an extended period. The first instalment of â¬3.1 billion was made in March 2011 and these will continue well into the next decade until the full amount, plus accrued interest, is paid to these zombie institutions. The final cost of repaying the promissory notes has been estimated at â¬48 billion and if these repayments continue to be made with borrowed money the total cost of the promissory notes will exceed â¬80 billion by 2030.

We will look at Anglo and INBS in more detail in a later section but it is important to remember that the cost of the promissory notes and the cost of the recapitalisation are not the same thing. The repayments on the promissory notes include â¬17 billion of interest. This is being paid to Anglo Irish Bank and INBS, which are state owned. They in turn are using the promissory notes to avail of emergency liquidity from the Central Bank of Ireland. They are paying interest to the Central Bank for this facility. The Central Bank will make a profit on this and will return the interest to the Exchequer as part of its annual surplus. The interest on the promissory notes is not a cost to the state as much of it will be returned.

In 2011 there was a further stress test and subsequent recapitalisation of the other four covered banks: AIB, Bank of Ireland, EBS and Permanent TSB. The Central Bank estimated that the four banks would need to be recapitalised by â¬24 billion in order to be in a position to absorb the losses projected over the next three years by the consulting firm BlackRock.

Significant haircuts undertaken with subordinated bondholders in the banks provided about â¬5 billion of this amount. Some asset disposals by the banks and private sector investment in Bank of Ireland reduced the amount to be covered by the state to just under â¬17 billion. Of this, â¬10 billion came from the further liquidation of the assets built up in the National Pension Reserve Fund so the additional debt from the bank recapitalisation was around â¬7 billion.

The â¬119 billion increase in the GGD from 2007 to 2011 can be broken down as follows:

- â¬13 billion to build up cash balances

- â¬59 billion to fund government services

- â¬47 billion for the bank bailout

Although it attracts the most attention, the banking disaster has contributed just 40 per cent of the increase in the GGD over the past four years. The next issue is where the debt level is going to go over the next four years.

At this stage the only thing certain to increase the debt over the next four years are the annual deficits. Some steps have been taken to try to control the deficit but it remains at very high levels. Between 2012 and 2015 it is estimated that a further â¬40 billion will be required to finance the annual deficits across all areas of government. The deficits for the four years are forecast to be â¬13.6 billion, â¬12.4 billion, â¬8.6 billion and â¬5.1 billion. This will put the debt at â¬206 billion in 2015.

This is substantially lower than some earlier estimates of our 2015 debt. For example, in early 2011 the IMF were forecasting that the 2015 debt would be â¬225 billion and debt sustainability was only possible if some very optimistic growth projections were used. However, since then there have been some positive developments for Ireland's debt dynamics.

The original EU/IMF programme set aside a â¬35 billion âworst case scenario' contingency fund for the recapitalisation of the banks, of which â¬17.5 billion was going to be borrowed. As we now know the 2011 recapitalisation required less than â¬7 billion of additional borrowing. The reduction in the EU interest rates will reduce the forecast by around â¬3 billion while there was a â¬4 billion reduction in the starting point because of a âdouble counting error' in the Department of Finance revealed in November 2011.