What If Ireland Defaults? (4 page)

Read What If Ireland Defaults? Online

Authors: Brian Lucey

Debt, Crises and Default from a Parliamentary Perspective

Sean is a professor of economics at Trinity College Dublin, represents Trinity College, University of Dublin in the Irish upper house of parliament (the Seanad) and is whip of the university senators in parliament.

Introduction

The membership of parliament in Ireland changed radically in the 2011 elections following the International Monetary Fund/European Union/European Central Bank (IMF/EU/ECB) bailout in late 2010. Of the 166 seats in the Dáil or lower house, 77 (46 per cent) were held in late 2011 by members who were not in the previous parliament. Of the 60 seats in the Seanad or upper house, 42 (70 per cent) were held in late 2011 by members who were not in the previous Seanad.

The crises in banking and the public finances illustrated by the bank rescue of 2008 and the national bailout of 2010 resulted in the reduction of seats held by the outgoing government from a majority of 83 (December 2010) in the previous Dáil to 19 seats in late 2011 held by the Fianna Fáil party and the elimination of its coalition partner, the Green Party, from any parliamentary representation. Fianna Fáil had dominated Irish public life for eight decades before the 2011 election.

The lessons for government in Ireland from the years 2008â2011 are that capture of politicians by the construction sector for over a decade leading to the property bubble and the capture of the government by the banking sector in 2008 are now opposed by the overwhelming majority of the public. The election results are loud and clear.

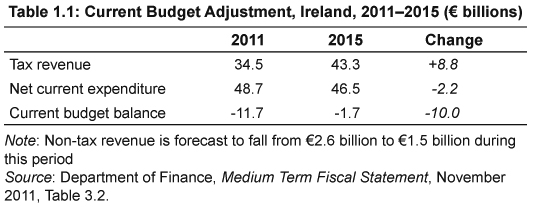

The lessons for governance are more complex and largely unaddressed. Widespread reforms are required if Ireland is to be rescued from its massive debt burden. Failures of corporate governance in the private and public sectors require institutional reform, and progress to date has been minimal. The main emphasis to date has been on solving the Irish debt problem by increasing taxation rather than addressing either expenditure or institutional reform issues. Table 1.1 shows that the adjustment of the current budget over the IMF/EU/ECB rescue period is dominated by tax increases. There are legitimate fears that by the end of the rescue period the institutions and policies which caused the crisis will remain unreformed. The massive rejection of the politicians associated with the Irish economic collapse will have been futile.

Capture and Lobbying

On the night of 29/30 September 2008 four Irish banks and two building societies secured government guarantees to underwrite their entire network. Murphy and Devlin

1

wrote that âGuaranteeing the banks was an extraordinary step. It meant that if any bank discovered it had unmanageable bad loans, the taxpayer would be liable.'

The bank guarantee was heavily criticised because of the costs involved, the failure to address moral hazard, the failure to consult other members of the EU and the Eurozone, the failure to address the causes of the financial problems of Irish banks and their failed regulatory regime, and the failure to convene a normal Cabinet meeting on the guarantee.

The Cabinet meeting was incorporeal on the basis that a meeting of all ministers could not be convened in time. This latter excuse is unconvincing. Several ministers lived within a few miles of Government Buildings. Ireland is a small country with a good motorway network. The government was represented in its dealings with the lobbying bankers by the Taoiseach, the Minister for Finance, the Attorney General and the Governor of the Central Bank.

Byrne and Ãornsteinsson

2

state, âthe capture of the state by an oligopolistic financial sector, due to excessive risk taking without consequence, was complemented by the failure of political institutions to anticipate the collapse.' The decision of the overnight incorporeal Cabinet meeting to bail out the banks without full Cabinet participation is merely another lapse in scrutiny and checks and balances in Irish public finances. Ireland has a rigid parliamentary whip system in which dissenters, three in 2011, are expelled from parliamentary parties. The Department of Finance lacked the competences required to assess banking policy. The Wright Report

3

found that only 7 per cent of the staff of the Department had a qualification at Master's level or above in Economics. The post of Governor of the Central Bank was filled from the Department of Finance repeatedly during the build-up to the crisis in 2008. Cooper

4

notes that âthroughout 2008 and early 2009 both the then Central Bank governor and financial regulator publicly defended the lending policies of Irish banks on many occasions, endorsed the strength of their balance sheets and decried suggestions that the banks might have walked themselves into trouble.'

Kinsella

5

notes that âthe liabilities of the banking system in Ireland are roughly four times the yearly income of the nation.' Phillips

6

estimates that âthe end result of the rescue was the generation by various mechanisms, including bank guarantees, of what Standard and Poor's estimate at â¬90 billion in new sovereign debt (counting likely future losses in NAMA [the National Asset Management Agency]).'

Banks and Borrowing

As Mathews

7

points out, âat 494 per cent of national income, Irish combined debt levels are the most crushing in the world.' This burden comprises, as a proportion of national income respectively, government debt at 137 per cent, household debt at 147 per cent and corporate debt at 210 per cent. As Phillips states:

Reckless financing in the Irish construction industry combined with a lack of enforcement of national banking regulations with cheap Eurozone credit financed twenty years of Irish economic expansion â¦. When the bubble burst the overextended construction sector collapsed, defaulting on its loans. This destabilised the Irish financial sector, resulting in the insolvency of almost all Irish private banks.

8

The Economist House Price Index 1997â2007 showed Ireland with the highest house price index increase, at 251 per cent, or almost double the average for the fourteen observations in the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries surveyed.

9

The highest price rise in Ireland was for second-hand houses in Dublin, from an average of â¬104,000 in 1997 to â¬512,000 in 2007. Ireland illustrates the quote from Paul Volcker in Roberts' chapter:

10

â“we borrow and borrow and continually spend and, so long as people are willing to lend, there is not sufficient pressure to do something about it in a timely way.”'

Ireland illustrates also the consequences of easily available borrowing. Fiscal discipline is undermined. The distinction between capital and current spending becomes blurred and items are labelled âcapital' in order to bypass a current budget constraint. Capital expenditure appraisal techniques, hardly at the frontier of economics today, were notably absent from the large Irish public capital programme.

11

Ireland experienced the problems of both Niskanen's bureaucracy and Baumol's disease.

The

Report of the Special Group on Public Service Numbers and Expenditure Programmes

12

(better known as the Bord Snip Nua Report) found an increase of 82 per cent in higher management staff in the civil service between 1997 and 2007 compared to a 27 per cent increase in civil service staff as a whole. The Irish system of social partnership increased the governance roles of senior civil servants, public service trade union leaders and public expenditure lobbyists at the expense of parliament. Centralised wage bargaining under social partnership increased the costs of public services by neglecting productivity increases in return for increases in public pay, and by extra awards for senior public servants through a now discredited system known as benchmarking, under which public pay at the higher levels in Ireland exceeded that in the countries from which Ireland sought rescue finance in 2010.

Lack of discipline in the Irish public finances is illustrated in the account by Brendan Drumm of his five-year term as the first chief executive of the Health Service Executive: âBetween 1997 and 2005, Ireland's annual health service budget tripled from â¬3.7 billion to â¬11.5 billion. Despite this, in 2006 Ireland was ranked 25th among the 26 countries included in the Euro Health Consumer Index'.

13

Over a twenty-year period the number of health service staff doubled to 112,000 in 2007. Problems of productivity and value for money were not confined to direct employees however, but extended to successful rent seeking by suppliers to the sector such as pharmacists and drug companies. Efforts to reduce drug costs were opposed by the industry and âby politicians from all political parties' in 2007:

It seemed to go unnoticed that the Health Service Executive team was representing the interest of the taxpayers in trying to reduce expenditure on drugs, which was out of line with most comparable countries and which was resulting in a reduction in other frontline services.

14

The European Dimension

Ireland and the other peripheral states illustrate the basic design faults in the Eurozone project, such as the lack of an exit mechanism, the one-size-fits-all prescription and the vulnerability of small economies to massive capital flows from the larger states. An early enthusiast for the Euro, Jacques Delors, is quoted in late 2011 saying that âthe Euro project was doomed from the start'.

15

Ireland lost the exchange rate and interest rates as policy instruments. The exchange rate was used successfully in the 1990s in the recovery from the debt crisis in the 1980s. Ireland's interest rate needs were contrary to those of the larger German economy, but the rates themselves were in tune with German requirements, and so were countercyclical in the Irish case. The warnings of Friedman on the adverse consequences of joining the Euro for Ireland

16

were ignored. Ireland joined the Euro as a full employment solvent country but had to be rescued in 2010 and as of January 2012 has over 14 per cent unemployment. Ireland also failed to face the issue of joining the Euro while its major trading partner, the United Kingdom, remained outside. Ireland also failed to understand the impact on Irish asset prices of capital flows from the larger EU economies. The EU before the single currency made substantial fiscal transfers to Ireland in structural funds and agricultural price supports. These promoted rent seeking by Ireland from the EU and weakened the incentive for balancing the public sector budget. The prospect of âfree money from Brussels' diverted Ireland from sound public finance. For example, EU money played a large role in spending â¬1 billion a year on FÃS, the state training body, in an economy which was at full employment. As Europe moves away from a common market and towards an extra layer of government the question arises whether extra government contributes to economic welfare or adds to overhead costs. Ganley's recommendation that we âtake the calculated but worthwhile risk to fully unite in a democratic and federal union, or we will see this project fall apart' is therefore a high-risk strategy.

17

Europe operated successfully for several decades as a common market based on free trade rather than extra layers of governance.

Parliament and the Public Finances

Ireland illustrates many of the difficulties caused by laxity in the operation of national finances. Weak public expenditure controls lead to an expanded bureaucracy which is both expensive and difficult to reduce as required over the economic cycle. Weak public expenditure controls increase the rewards for lobbyists and rent seekers. The ease with which the bank lobby imposed massive costs on Ireland relative to GDP by securing the bank guarantee in September 2008 ranks as one of the most successful lobbying exercises ever. A further cost of weak public expenditure controls is the diversion of the banking sector from the skills of risk assessment of investment in the market economy to risk-free lending to governments and bodies with government guarantees. The success of lobby efforts was in part due to the lack of proper scrutiny of the political class by voters. The presentation of parliament to the citizens in the print media is dominated by image impressions to the virtual exclusion of matters of substance. Contact between the citizens and the many new members of parliament is more likely through social rather than print media.

Walsh criticises âthe failure of the media to put any brake on the frothy excesses of the boom years' and cites the case that âmost financial journalism is now PR driven. The news agenda is shaped by journalists rewriting press releases'.

18

In the boom years the Irish print media gained advertising revenues from the property price spiral. Many investigative journalists in Ireland continue to join PR companies in their later careers.