What If Ireland Defaults? (18 page)

Read What If Ireland Defaults? Online

Authors: Brian Lucey

Post-Crisis Recovery

According to Moody's research,

3

the Russian default â $72.71 billion â accounted for over 96 per cent of the total worldwide default volume of $76 billion in 1998. The event constituted the second largest default (after Argentina's $82.27 billion default in November 2001) over the entire period of 1998â2006. Furthermore, according to Moody's, the Russian default was associated with the lowest recovery rate (18 per cent) of all defaults over this period. Following the August 1999 and February 2000 restructurings debt burdens overall fell to a more sustainable level of 59.9 per cent of GDP in 2000, down from 99 per cent in 1999. The appointment of a new government, with Viktor Chernomyrdin returning as Prime Minister, was the first stage of the stabilisation. Chernomyrdin had served as Prime Minister in 1992â1998, a period that taught him some core lessons. Firstly, that ruble devaluation was inevitable and losses of foreign reserves cannot be sustained without destroying the economy. Secondly, the political balance between the Duma and the presidential administration was a precondition for success of longer term reforms. And thirdly, that the state finances had to be scaled back on the expenditure side in order to unwind accumulated internal debts.

However, Chernomyrdin's second tenure did not have the full backing of Yeltsin, who was battling for his own political survival. The Russian economy ended 1998 with GDP down 5.345 per cent in constant prices and the country's GDP fell from $404.9 billion in 1997 to $271 billion in current prices in 1998 â a level that threw Russia back to its 1993â1994 average. Devaluation pushed domestic inflation to 84 per cent, primarily impacting imported goods. Crucially, Chernomyrdin failed to win over the Duma and enact any significant reforms.

At the same time, a 75 per cent devaluation of the ruble helped push Russian exports. The Russian current account posted a deficit of 0.02 per cent of GDP in 1997 and by the end of 1998 was running at a surplus of 0.08 per cent. In 1999 the external balance of the Russian economy rose to a massive 12.6 per cent surplus, and thereafter, in 1999â2008, current account surpluses averaged 10.1 per cent of GDP per annum. If in 1998 Russian economy's trade balance contributed roughly $219 million, by the end of 1999 the same figure stood at $24.6 billion and by 2008 it rose to $103.7 billion. In the early post default years much of the economic recovery was attributable to a decline in consumer imports and the subsequent rapid substitution of domestically produced goods for foreign imported goods. After 2002, rapid increases in oil and gas prices helped to accelerate current account growth momentum. However, monetary and fiscal policies also helped. The transition of power from Boris Yeltsin to Vladimir Putin on 31 December 1999 ushered in a completely new era of political stabilisation (although this was achieved at the expense of rolling back some of the reforms established under previous rounds of democratisation in 1991â1997) and a focus on some core structural reforms.

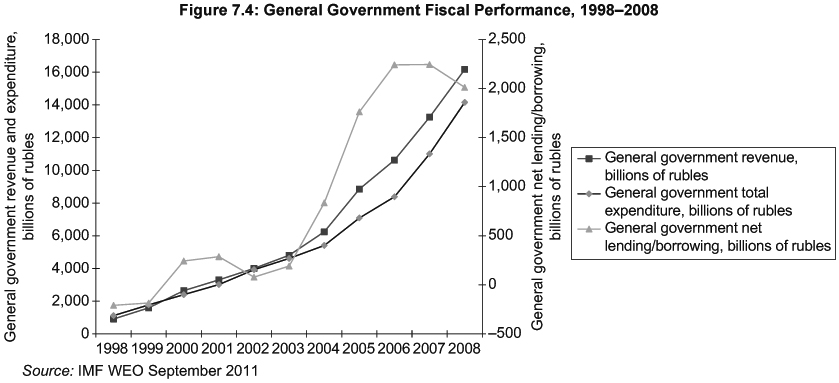

In particular, the new administration moved swiftly to address Russian fiscal deficits, as illustrated in Figure 7.4.

This was achieved in three core steps. Firstly, the Russian state implicitly recognised the inability, at least during the recovery stage, to finance a significant extension of the welfare state beyond its core functions of supporting education, basic health and limited social welfare. This led to the renewed push toward a reduction in public spending and rationalisation of budgetary allocations.

Secondly, the government dramatically improved its enforcement of tax collection and set rapidly on course to restrict tax competition from the regions. Rolling back excessive autonomy granted to the regions by Boris Yeltsin, Vladimir Putin managed to dramatically lower federal tax revenue slippages due to regional authorities' corruption and collusion with private enterprises.

Thirdly, in 2001 the government launched ambitious tax reforms which saw a reduction in the overall tax burden on individual incomes, streamlining compliance and, once again, beefing up enforcement. A progressive personal income tax system that imposed a range of tax rates between 12 per cent and 35 per cent was reformed into a flat tax system with single rate of 13 per cent. Between 2000 and 2001 income tax revenues increased from 175 billion rubles to 256 billion rubles, a rise of 46 per cent in just one year. The annual rate of growth in income tax revenues for 2000â2004 hit almost 35 per cent and the overall share of income tax revenues in the overall government revenues rose from 8.3 per cent in 2000 to 10.6 per cent in 2004. In addition to reforming personal income tax rates, the Putin administration also reduced the headline corporate tax rate from 35 per cent to 24 per cent in 2002. The initial impact of this change was to reduce corporation tax revenues in 2002 from 514 billion rubles in 2001 to 463 billion rubles in 2002. Boosted by economic growth and the reduced burden of compliance, as well as by the improved enforcement of tax codes, corporation tax revenues rose to 868 billion rubles in 2004. Reforms of tax codes and the lowering of the corporation tax rate also explain the rapid expansion of investment in the economy. In 2002 the inflow of FDI into Russia amounted to $4.0 billion. This increased to $9.4 billion in 2004.

Russia was able to access funding markets relatively quickly post-default, as was the general experience with defaults in the 1990s. Gelos et al.

4

found that for defaults that took place in the 1990s the average return to funding markets took 3.5 months, as opposed to 4.5 years for defaults during the 1980s. However, in the case of Russia the return to the markets initially was a costly one with 2003â2005 bond spreads remaining above 200 basis points, despite the fact that the country was showing very robust rates of economic growth and double digit surpluses on its current account. This is most likely related to three factors. The Russian default, as noted above, was characterised by extremely low rates of recovery on government bonds. In addition, most of the Russian government debt pre-default was held by foreign investors, implying a much more significant impact on foreign bondholders. Lastly, the Russian economic recovery was perceived to be primarily driven by rising oil prices â a perception that is well grounded in reality.

The immediate disruption caused by the default and the currency crisis was painful. Unemployment rose from 10.8 per cent in 1997 to 13.0 per cent in 1999 â the peak of official unemployment for the 1990s. In some areas, especially in industrialised central Russia, the collapse in investment led to the effective shutting down of industrial production. In many regions unemployment reached 18â20 per cent, and these numbers concealed the fact that, in addition to massive jobs losses, many in employment saw their wages delayed. Payments arrears and a stalled banking system meant that backlogs of wages rose to 50â60 per cent in cities such as Nizhny, Novgorod and Penza. Moscow itself weathered the storm much better due to more efficient payments systems and the city's government's more proactive stance on payments to its employees.

The crisis materialised at the time when many Russian industries were at the tail end of the process of realisation that state orders and older patterns of production, reliant on government and military orders, were coming to an end. This meant that many impacted enterprises, especially the larger ones, were already on the cusp of transitioning to more market-driven economy. The crisis accelerated this process. The collapse of the ruble in 1998 improved the competitiveness of domestic products and services. As imports prices quadrupled virtually overnight, domestic industrial and agricultural output increased. For example, within two years of the crisis, unemployment in one of the core industrial regions â the region of Penza â fell from 18 per cent to 1.5 per cent and industrial output grew by 141 per cent. Remonetisation of the economy following the ruble devaluation provided the necessary liquidity to pay down salaries and wages arrears and consumer spending rose by late 1999. The government policy of centralisation of authority away from a regional distribution of power â the default option pursued by the Yeltsin administration â also helped. The Kremlin forcefully re-asserted central control over the regions and this political move was backed by Moscow's efforts to repay regional governments' debts to state employees. Within three years of default, the demand for skilled workers rose and the Russian middle class regained all income and savings losses sustained in the crisis.

One feature of the Russian crisis was the collapse of the banking system. The banking crisis in the Russian case was driven by a number of factors related to the broader problems in the Russian economy. During the early 1990s, Russian industrial enterprises set up a number of their own banks for the purpose of enhancing internal control of their capital and using industrial funds to earn additional income from lending. By 1996â1997, however, the system of credit in the country had firmly shifted away from lending to enterprises and was more geared toward booming domestic credit and government securities. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD),

5

by the end of 1997 the commercial banking sector held almost 75 per cent of ruble-denominated deposits in form of federal government debt. At the same time, OECD data suggested that private sector credit fell from 12 per cent of GDP in 1994 to 8 per cent in 1997. High interest rates and banking sector inefficiencies have meant that large segments of the Russian economy were operating on informal credit and barter.

Following the default, remonetisation of the economy has meant that black market credit and payments transactions, especially those involving barter, have declined. This decline was almost immediate, as noted in Huang et al.,

6

who show that barter and non-cash payments fell 20 per cent in 1999 and continued to decline in importance in 2000 and 2001. Subsequent tax reforms streamlining personal and corporate income taxation measures and compliance added further strength to the process of normalisation of the Russian payments systems.

The consolidation of the banking crisis post-default and the collapse of overall government asset markets meant that the banks were incentivised to start lending to the real economy. Between 1998 and 1999, the volume of ruble loans rose from 123 billion rubles to 293 billion rubles. The volume of total loans rose from 310 billion rubles in 1997 to 597 billion in 1999 and 1,418 billion in 2001.

The consolidation of the banking sector saw three core state-owned banks capturing some 80 per cent of the liquid banking assets in the country â a move that instilled more confidence in the banking system's stability within a population that lost all trust in private banks during the default. According to Huang et al., the collapse of the assets acquisition conduit via government securities meant that surviving banks were forced to seek new assets in the commercial lending markets. The cost of credit therefore declined and many enterprises were able to access new credit. The virtuous cycle of improving credit ratings for many enterprises, spurred on by robust economic growth in 2000â2002, was reinforced by these developments in the banking sector. Reversal of the capital flight out of Russia, in part largely predicated on capital controls imposed during the crisis, also helped.

The banking sector collapse and ruble devaluation have significantly reduced the overall dollar equivalent volumes of household deposits. In June 1998, total household deposits stood at around $40 billion. This number fell to $12.1 billion by December 1999. Likewise, capital controls have meant that many commercial creditors were made insolvent almost overnight. As reported by Euromoney,

7

a World Bank study found that in 1999 the majority of losses within the banking system in Russia were driven by commercial loans, not the government assets bust. Specifically, loan loss provisions amounted to $64.3 billion in 1999 and 34 per cent of net charges to banks' capital. Losses on government assets were only 13 per cent.

These processes crystallised losses on banks' balance sheets and forced significant reforms of the banking sector, including much tighter supervision and stricter lending rules. But the main thrust of reforms was the significant reduction in cross-ownership of banks by industrial companies in the private sector. In the early 1990s, large number of banks was created within the industrial groups that were privatised during the Yeltsin era, and especially during loans-for-shares schemes. These banks acted as conduits for industrial oligarchs' access to government lending arbitrage. The banks borrowed cheaply from the Central Bank of Russia and rolled borrowed funds into GKOs. Some of these loans were used to further increase industrial companies' access to capital that was used to finance purchases of state-owned assets in extraction sectors and finance bidding for lucrative licenses. Post default, a large number of these banks went bust and the remaining ones were consolidated in super-sized commercial banking entities, such as Gazprombank. This consolidation, and state backing for the larger banks, has meant that domestic depositors, including retail savers, improved their perceptions of the banking sector in general. A deposit insurance scheme also backed by the state that was put in place in December 2003 further reinforced this build-up of confidence. The result was an increase in deposits that continued unabated from 1999 through the period of post-crisis shock.