What If Ireland Defaults? (17 page)

Read What If Ireland Defaults? Online

Authors: Brian Lucey

The economic unravelling began in the foreign exchange markets in the last quarter of 1997 when, following the Asia Pacific currency crisis, the Russian ruble came under sustained devaluation pressures. By late November, the ruble was sustaining a deep speculative attack, just as the oil and gas prices began to moderate, signalling a twin currency valuation and currency demand crunch. Ruble overvaluation was sustained on the basis of the core government objective to keep inflation under control. Within just one month â in December 1997 â the Central Bank of Russia was forced to incur foreign exchange reserve losses of some $6 billion trying to defend the ruble. The problem was further exacerbated by the structure of the short-term bills (GKOs) issued by the Russian government, which contained an explicit hedge against rubleâdollar devaluation. This proviso was a direct outcome of the poor quality of expert advice Russia received from the international lending bodies, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

Inflationary control measures coincided with a defence of the overvalued ruble throughout most of 1998. The Central Bank of Russia attempted not only to deploy open market operations to sustain ruble valuations, but also increased the lending rate â the rate at which the Central Bank lends short-term funds to registered banks â from 2 per cent to 50 per cent in early 1998. With the developments in the Asian currency crisis in the background, in December 1997 the IMF re-launched loans disbursement to Russia, with a loan of $700 million. At the same time, the IMF urged Russian authorities to close the fiscal deficit gap in part by improving tax revenue collection.

Sustained pressure on the ruble accelerated into 1998 as it became increasingly apparent that economic growth would not reach the 2 per cent budgetary assumption. Tax reforms in February 1998, aimed at streamlining tax codes and improving tax collection, came in too late to reassure foreign investors that the Russian government's deficits were on a sustainable path. According to analysts, the Russian federal tax system of 1992â1999 was:

⦠characterized by extreme instability, complexity, and uneven distribution of tax burden, weak administration, low competitiveness and poor transparency. High rates of income and profit taxes were ones of the biggest business development disadvantages and because of weak administration of these taxes; they created the background for the shadow economy.

2

The February 1998 reforms proposals were put in place primarily to alleviate IMF concerns regarding fiscal sustainability and to allow the IMF to extend its loans to Russia by one year. But the reforms, favoured by the Yeltsin administration, were not supported by the broader political establishment. The reforms did run into trouble in the State Duma (the lower house of the Russian Parliament), which briefly suspended hearings on their adoption in July 1998. The version of tax reforms that was finally approved on 16 July failed to commit to implementing the full $16 billion in tax revenue measures, as the State Duma scaled back President Yeltsin's proposals for higher sales taxes and land value taxes. In line with Duma approval, the IMF announced $23 billion worth of emergency loans to the Kremlin on 13 July 1998, well in excess of the normal special drawing rights (the unit of IMF capital-determining currency) allocations allowed.

Even before this disbursement took place, the Russian government had repeatedly tried to secure IMF funding since late March 1998. As financial conditions continued to deteriorate through the end of the first quarter of 1998, President Boris Yeltsin took a series of steps attempting to bring under control the twin economic and political crises. On 23 March 1998 he unexpectedly dismissed the entire Cabinet, sacked Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, and appointed the heretofore unknown 35-year-old Sergei Kiriyenko as the head of government. Kiriyenko's inexperience in the federal political structures proved a fatal error. The new prime minister's first political appointment took place in 1997 when he was given the portfolio of the First Deputy Minister for the Fuel and Energy Sector. Thus, prior to his appointment as Prime Minister, Kiriyenko had less than twelve months' experience in government and no direct experience in federal politics, and came from a corporate background.

The appointment of Kiriyenko as the country's prime minister acted to further destabilise the already fragile political balance between Yeltsin and the State Duma, as well as between the federal state and regional authorities. It took Yeltsin until 24 April to finally secure Duma approval of the new prime minister and even that required forceful threats from the President to the parliament, including the threat of dismissal.

Kiriyenko showed his lack of experience when in a public interview he stated that Russian federal tax revenues were running 26 per cent behind targets. Instead of directly and transparently promoting government budgetary plans for reduced deficits, Kiriyenko made a bizarre statement that the federal government was, at that point in time, âquite poorâ. Kiriyenko's public gaffe reinforced an already growing public perception that the ruble was to be devalued against the US dollar â the preferred store-of-wealth currency in Russia in the 1990s. In May 1998, Sergei Dubinin, chairman of the Central Bank of Russia, made another public statement that referenced the possibility of the Russian government facing a full-blown debt crisis between 1998 and 2000. Both Kiriyenko's and Dubinin's statements added fuel to the fire of speculative attacks betting on a ruble devaluation and rapid withdrawals of funds from Russian banks. Both represented the degree of policy incoherence that characterised the later period of Yeltsin's administration. Both were newsworthy items in markets already stressed by the continued Asian currency crises.

Selling pressures on Russian GKOs accelerated. It is worth noting that GKOs were accumulating in the hands of large institutional investors with a significant appetite for risk. In addition, these instruments were also held on banks' balance sheets. With GKO prices collapsing, foreign investors began aggressively deleveraging out of the GKOs. However, the same did not take place in the Russian banking sector, with Russian banks continuing to accumulate GKOs in a speculative bid to boost profits, while simultaneously relying on the sovereign nature of these bonds as a âguarantor' of their safety. Deleveraging by foreign investors was met by the Russian treasury with increases in the short-term yields on reissued GKOs and by May 1998 government bond yields had reached 47 per cent. Only then did the Russian banks enter the process of gradually reducing their exposures to the new debt issuance and even then the Russian banks' deleveraging out of GKOs was slow and mostly concentrated among a handful of medium to large banks exposed to international banking services competition.

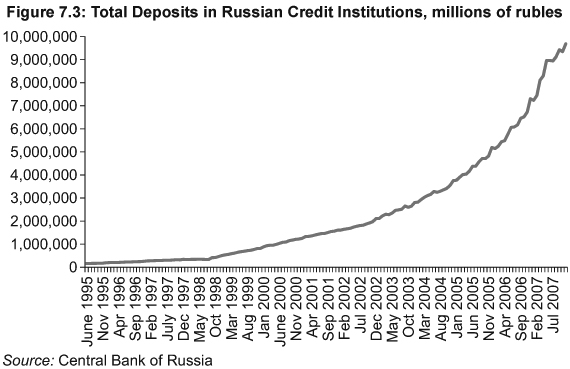

Meanwhile, retail deposits started to dry out as domestic savers switched into hoarding cash. Demand for dollars rose both externally and internally, since the US currency served as the main store of value since the late Soviet era. Capital expatriation rose dramatically. Between 1997 and 1998, growth in ruble deposits by Russian residents fell from 30 billion rubles per annum to 1.3 billion rubles per annum, despite the fact that the money base continued to expand as shown in Figure 7.3.

The deleveraging was amplified by the aggressive drive by the Russian authorities to improve tax revenue collection. As part of the tax reforms back in 1997 Russia had created a much more effective and less corrupt treasury system which was modelled on a similar system already in operation in the city of Moscow. The agency concentrated its efforts on the extraction industries with access to foreign currencies. Unfortunately, these sectors were also heavily reliant on imports of capital equipment to sustain their production growth. Many exporting firms, pushed to the limit by federal tax collectors, were suspending payments on equipment purchasing contracts. As the price of oil, and to a lesser extent natural gas, continued to trend downward, reaching $11 per barrel in May 1998, many voices within the corridors of power were speculating about the need for drastic devaluation of the ruble. These rumours helped to push up the risk premiums on Russian GKOs in the international markets and precipitated rounds of foreign exchange hoarding by exporters and Russian banks. As the result, the domestic banking system was effectively split into two, with foreign-trade-engaged larger and state-owned banks running hard currency balance sheet operations to hold increasing reserves of foreign liquidity, and smaller domestic savings banks becoming completely exposed to ruble valuations. As the Central Bank of Russia continued to pump billions of dollars into foreign exchange markets in a futile attempt to defend the ruble, the former group of banks became extremely important to the Russian federal authorities, in part ensuring that following the default these banks will be taken into state ownership and preserved. Meanwhile, purely domestic banks in the second group were clearly falling out of the market operations and becoming less important to the Central Bank in its crisis management mode, thus ensuring their eventual bankruptcy post-default.

The structure of taxation was decisively shifting away from supporting capital investment and in the direction of reducing tax credits available to businesses and banks. For example, 1998 tax reforms included a cancellation of the practice whereby government departments and ministries, as well as state-owned enterprises, issued tax credits in payment for private sector supplies of goods and services.

Even with these draconian changes, the federal government was able to increase tax collection only marginally to approximately 10 per cent of GDP. Meanwhile, the budgetary performance was going from bad to worse. In 1997 the deficit reached 6.1 per cent of GDP and the government hoped to reduce it to 5 per cent in 1998. However, two factors underpinning these plans never materialised. Firstly, the deficit target for 1998 was based on assumed growth of 2 per cent in real GDP, while real growth came in at a contractionary -5.35 per cent instead. Secondly, Budget 1998 was computed on the basis of the highest interest rates on government debt of 25 per cent. By mid-1998, interest rates stood at six times that, implying that debt servicing consumed over half of government revenues. The end result was a fiscal deficit that reached 7.95 per cent of GDP in 1998.

By the end of May 1998, demand for GKOs began to collapse with yields rising to over 50 per cent and weekly bond auctions failing to attract sufficient numbers of bidders to allow for the full allocation of bonds in the market. This put pressure on the government that required an ever-increasing frequency of issuing new bonds to roll over the existent debt. Shrinking demand for GKOs was thus met by dramatically growing supply of these bonds. The Central Bank of Russia continued to hike lending rates, reaching 150 per cent. Dubinin attempted to calm devaluation fears by saying, âWhen you hear talk of devaluation, spit in the eye of whoever is talking about it.' Russian asset markets reflected the fate of the GKOs with markets experiencing massive sell-offs. On 18 May the Russian stock market registered a 12 per cent drop, and in the first six months of 1998 stocks were down 40 per cent on 1997 levels. These developments prompted James Wolfensohn, the head of the World Bank, to declare the Russian market to be in crisis and the Chairman of the Russian Securities Commission to respond with a statement that the market's situation was ânothing other than a crisis'.

By June 1998, Central Bank interventions in the currency markets were draining $5 billion of reserves as Russia headed toward a September deadline for the redemption of billions of dollars' worth of ruble- and dollar-denominated corporate and government debts. A July 1998 IMF assistance programme injected $4.8 billion in funds designed to shore up the collapsing GKO markets, with an additional $6.3 billion committed for later months. Yet, in the very same month, capital outflows from Russia, Central Bank interventions and declines in oil and gas revenues due to falling prices shrunk the money supply by approximately $13 billion. Even with that, IMF funding was clearly not going to come at the rates required to buy significant time. Overstretched by the funding requirements of the Asian currency crises of 1997â1998, the IMF had to dip into emergency credit lines itself â something it has not done since 1978 â to find money to finance the first tranche disbursal to Russia. This did not go unnoticed by foreign investors who accelerated their selling of GKOs and other Russian assets following the IMF announcement.

The 13 August stock market crash of 65 per cent precipitated the end of the Russian government's efforts to defend the ruble. Following the stock market crash, GKOs yields rose to over 200 per cent. On 17 August 1998, the Russian government enacted drastic devaluation, froze domestic bank accounts and declared a moratorium on debt repayments to foreign GKO holders, while fully defaulting on domestically held debt. Commercial accounts in the banks were frozen for 90 days and many companies ended up losing all their deposits and payment streams as dozens of banks went bust virtually overnight. On 24 August the government fell with Prime Minister Kiriyenko dismissed by Yeltsin, and on 2 September 1998 the Central Bank abandoned interventions in the foreign exchange markets, allowing the ruble to float against all currencies.