What Stays in Vegas (7 page)

Read What Stays in Vegas Online

Authors: Adam Tanner

Customers at a Total Rewards counter at Caesars Palace. Source: Author photo.

Soon after Loveman hired him in 1998, Mirman toured Harrah's in Las Vegas, a former Holiday Inn located across the Strip from Caesars Palace. As they passed a long line leading to a restaurant buffet, the property's manager kept stopping to greet people.

“Who are those people?” Mirman asked.

“Those are some of our best players,” the manager said.

Mirman was taken aback. “Our best players are standing in line waiting for the buffet? Why would we do that?” he thought.

7

Harrah's eventually replicated the model embraced by US airlines and added different membership levels. The most active customers would get greater perks, including shorter buffet and check-in lines.

Mirman and his team toyed with whimsical tiers such as “Lucky Cherries,” “Three Sevens,” and “Diamond Jubilee.” They tested the ideas on customers and found they hated the goofy names; they took their gambling seriously. In 2000, Harrah's settled on Gold, Platinum, and Diamond levels, inspired by conservative names used by credit card companies.

8

The company added a new top level, Seven Stars, four years later.

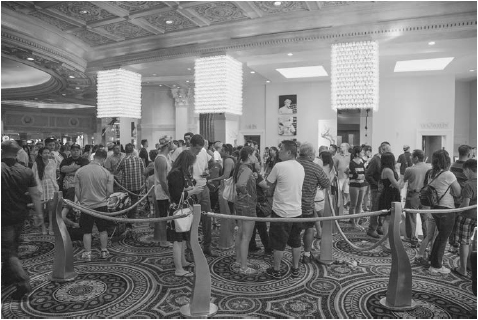

Buffet line at Caesars Palace. Source: Author photo.

After Mirman, Loveman hired David Norton. Norton thought a lot about the people traditionally ignored by casino management. He saw great value in the retired grandmother quietly feeding a steady stream of coins (and later paper) into slot machines in the corner of the room. Under the old system, such players did not spend enough on any one day to merit special attention. But they came twenty, thirty, or forty times a year for their Friday or Saturday night entertainment. Norton concluded that the vast majority of the company's most valuable customers followed such a pattern.

“Previously in the industry, people who were good daily value customers got special treatment,” says Norton, who ended up as the senior vice president, serving until 2011. “You could spend $500 a day once a year and be a VIP, and you could spend $100 a day and come thirty times a year and you weren't a VIP.”

9

Norton considered how a sixty-year-old woman who lives in New Jersey near Atlantic City would stack up against a twenty-eight-year-old guy from Manhattan. It may be that two visits a year to Atlantic City is all they can expect from the New Yorker, but the nearby retiree might come ten times. Thus the company should give her special deals to show up more often, based on her specific profile. “We are going to talk to her differently and say, âIf you are more loyal to us, you could achieve Platinum or Diamond status,'” says Norton, an MBA with a background in the credit card industry. “Because we think she is going to the market somewhere else and we are only getting a small fraction of her spend.”

Norton recommended to Loveman that Harrah's create more benefits for the repeat customer who spends modest amounts on each visit. Loveman agreed. So the company started offering these regulars special perks such as free valet service, faster check-in, and better buffets. The New Jersey regular and other customers like her felt special. They kept coming back.

Harrah's still had its headquarters in Memphis when Norton started. He received a cushy office in what he felt was a country club atmosphere. As he dug into the company's database, he was impressed to find that Harrah's had centralized gambling information on customers from across what was then fifteen different properties. Yet he soon realized local managers did their own marketing, often disregarding the data and following their instincts. They largely ignored headquarters, even though the great value of all the customer data could only be realized with a unified approach.

Norton struggled to get local casinos to embrace the mantra of personal data. One day he visited Harvey's Lake Tahoe, a company property that lured gamblers from San Francisco and other parts of California. He told them he wanted hosts at the casino to spend one

day a week calling new clients and encouraging them to return. The message was not welcome. “The daggers I got from those hosts was amazing,” he said. “But it completely revolutionized the business.”

Some on Loveman's staff ruffled feathers with unbridled arrogance. Norton recalls one Harvard graduate on his team who was as smart as anyone he had ever hired. Yet he fired her after a few months. No one ever wanted to work with her because of her attitude. Sometimes, the old-timers

did

know more than the whiz kids. The math nerds, many of whom had cut their teeth on Wall Street and as well-polished consultants, were often surprised by who spends the most gambling. They expected that lawyers, doctors, bankers, and consultants would be their best clients. Yet often the big gamblers ran small businesses such as dry cleaners, Chinese restaurants, or plumbing companies. “They don't look like the people you expect to have money,” said Randy Fine, a former Loveman student who later became head of Harrah's Total Rewards loyalty program. “Most Harvard Business School people struggle in the business and most wash out. And the reason is that people who go to a place like Harvard Business School believe that people who have money look a certain way.”

As Harrah's relentless focus on personal data and marketing showed results, old-timers grumbled that the whiz kids had subverted the spirit of old Las Vegas. “Casinos used to be run by individuals,” says Eddie LaRue, who still tells stories about Benny Binion from half a century ago. “Now it's a total disaster. You've got people who don't know anything about running a casino.”

Former Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman, who worked as a criminal defense lawyer in that era, remembers going to the now-defunct Thunderbird Hotel with his wife, where he would see singers such as Sarah Vaughan and Frankie Laine. “They didn't charge. They would bring us a free drink and hope that if we had any money in our pocket we would leave it there,” he recalls. “Now everything has changed. Now the bottom line, the bean counters have said that every department has to make money.”

Casino Data Gathering in Action

What the Casino Knows

Gary Loveman and his math nerds do not wander casino floors personally sizing up customers as Benny Binion and old-time Vegas hands once did. Rather, they study data about customers' past visits and project their potential future value. Just watching someone at a gaming table or slot machine for as little as sixty minutes makes it possible to predict how valuable a gambler may be in the future. It all comes down to how much someone typically bets, how many bets in a row he places, and how skilled he is. Such personal data is so valuable that Caesars sometimes reimburse newcomers for up to $100 in losses if they sign up for the rewards program and gamble for an hour.

The data gathering begins soon after a gambler walks into the cavernous casino lobby. A slight haze may linger from smoke (in the United States most casinos are among the last great refuges for those who enjoy cigarettes). A subtle perfume scents the air, pumped in to create a specific memory sensation. The gambler looks for her favorite slot machine and plops down. She reaches into her wallet and pulls out her Caesars Total Rewards loyalty card. She reaches toward a card reader surrounded by dotted orange lights. It turns green after she inserts the plastic card. From that moment, the casino records everything, starting with how much cash and paper ticket value she puts into the machine (coins were phased out more than a decade ago).

Caesars know exactly how many times she pushes the button triggering the electronic wheels to spin in random combination. They

know how much she is losing (or, less often, winning) from the moment she starts. The law of averages means that everyone will lose over time. Yet the casinos want her to keep returning, so they will do everything they can short of rigging the machines to mitigate a particularly bad day. If she loses far more than she traditionally wagers and far worse than the game's mathematical odds predict, a host, tipped off by a message to a smart phone, might arrive with a coupon for a free buffet to cheer her up. The logic? A bad day could inspire a gambler to defect to another casino to change her luck.

From time to time a host will greet elite-status slot machine players. At Caesars Palace, that might be Holly Danforth, a striking six-foot-tall blonde in her late twenties who aspires to become an actress or model. She introduces herself and addresses the player by name, which she knows from the data on her cell phone. “Most of the time they are very shocked,” she says. “They ask, âHow do you know that?' I tell them it's by their participation in Total Rewards.” She then gives out a business card and invites the player to contact her for any future assistance. If the player is a man who makes a pass at her, something she says happens all the time, she tries to gracefully extract herself and continue toward the next VIP.

Taking a break in the action, the gambler heads to one of the casino's many restaurants. The maître d' asks if she is a Total Rewards member. The waiter hands her a menu with two rows of prices, with a few bucks off each item for loyalty members. Or she could sign up for six all-you-can-eat buffets within a twenty-four-hour period at the discounted price of $47.99.

1

Caesars record exactly what she orders and over time chart her favorite foods. Capping off the evening at a show, she hands in the card to buy tickets, giving the management insights into what kind of entertainment she prefers.

In a fast-moving table game like craps, a supervisor notes down bets by visual observation, less precise monitoring than with slot machines. A player can later check credited points on a casino computer. If the gambler feels shortchanged, management can review a videotape of betting.

2

The supervisor also keeps a close eye out for players trying

to game the system. Some bet especially heavily when the supervisor comes into view, hoping they will be credited with more loyalty points. Others quietly pocket some of their own chips to exaggerate their losses (casinos are especially keen to lure back losers with generous future offers). The company is considering spending tens of millions of dollars to buy chips embedded with radio-frequency ID transmitters, which would allow the casino to track bets to the exact dollar.

In all, Loveman says, Caesars casinos know: “Did you respond to an offer when you came to the facility? Are you a resident with us at the hotel or not? When do you come? How long do you stay? What game do you play? How intently do you play it? What's the average wager? What sort of success did you have in the game? Were you a big winner, a big loser, an average winner, an average loser? Did you eat when you were with us? Did you go to the show? What kind of dining habits do you have? Do you shop?”

Rod Serling's old

Twilight Zone

episode, titled “The Fever,” portrays a slot machine that knows the elderly husband's name, Franklin, and beckons him in an ominous voice. His obsession eventually drives him mad.

3

Today Franklin might receive a direct solicitation for his business by mail, email, or smart phone. A host might also call him up to see how he is doing.

Some critics say all this clever marketing exploits those with a particular weakness for gambling, especially those who suffer from gambling addiction. Loveman responds that while gambling addiction is a real issue, 98 percent of his clients can dispassionately decide whether to take advantage of a marketing promotion. These clients can rationally decide to buy or not in the same way they might review a new offer for books or products from

Amazon.com

.

“For the 2 percent of the people who are addicted, there is no evidence to suggest being good marketers is really the issue. The addiction has to do with lots of other issues, and there are mental health circumstances,” Loveman says. “It's not whether or not the guy who runs the casino is especially capable or incapable of offering them things that they care about.”

4

Catching Whales

By tracking a gambler's last visit, a casino has information that can help lure him back in the future. Such logic motivates many companies far from Las Vegas to collect our personal data. Whether it is a local restaurant, airline, or online retailer, businesses want to know as much about us as possible, hoping to gain an edge in marketing. Some firms are more successful than others in using customer information, and that's why many have studied Caesars for insights.

Caesars give customers a choice to share their data, and patrons like Daniel Kostel do so willingly and enthusiastically. A salesman at an asset management firm in Los Angeles, Kostel visits Las Vegas about once a month. The bachelor loves blackjack and typically wagers $100 a hand. On a good night, he wins a few thousand dollars. If things go less fortuitously, he heads out the door that much poorer. He is not a huge gamblerâwhat the industry dubs a “whale”âbut he spends a lot more than a retiree cautiously playing penny slot machines. For years, Kostel alternated between casinos along the Strip, making him what the industry labels “promiscuous.” One night he dropped by Caesars Palace at the Strip's fifty-yard line.