When Satan Wore a Cross (4 page)

That was police speak for an “inside job.” Marx was asserting, however well politically, that an insider who knew the chapel and its environs well, especially the sacristy, had committed the murder.

The sacristy was bare of furniture, save for the aforementioned chair, three small wooden utility tables, and two portable kneelers. Normally found on the small table in front of the window, someone had deliberately placed the kneelers in an unusual place under the Twenty-third Street side window. Usually stored in the cabinet behind the table, a cardboard box containing altar decorations and draperies had been placed on a table in front of the storage cabinets. Margaret Ann had moved these items just prior to her murder.

Father Swiatecki came in to check that nothing was missing. He did a quick inventory. It appeared nothing had been stolen or tampered with. Marx wrote in his notes that the light switch was on when Sister Madelyn Marie found the body. While the murder had occurred in the sacristy, the killer might have come through the chapel to commit the crime. Time to check out the chapel.

Lying on top of the altar were assorted boxes of pins that had been placed there by Margaret Ann. A wooden chair, similar to the one found in the sacristy, had been placed in front of the altar. The chair was turned sideways to allow Margaret Ann to stand on it to reach the high draperies behind the altar. The altar cloth that was found wrapped around Margaret Ann’s arm had previously been attached with tape to the top of the altar where Margaret Ann had been working.

Searching the pews, on the middle right side, Bodie found a prayer book and small purse. At first, the cops thought they were Margaret Ann’s, until Sister Mary Clarisena appeared to claim them as her own. Not so the neatly folded altar cloth. Marx found it in the first pew, left side, at the extreme right end of the chapel. It was exactly where Sister Madelyn Marie had placed it, after finding it lying on the floor in the hall.

Marx gave it to Sister Kathleen. She unfolded it slowly. As she did, it became evident that it was bloodstained. After a few more questions, Marx determined how the cloth had gotten into the pew through Sister Madelyn’s actions. He gave it to Bodie for bagging as evidence. When it was brought into headquarters from the crime scene, the TPD would mark, tag, and place it the evidence safe. The crime lab would later examine the cloth and see what they could come up with.

The chapel’s highly polished terrazzo floor was pristine. There was absolutely no evidence to indicate that there was any type of struggle at or near the altar when Margaret Ann was working. Plain and simple, the killer had surprised and killed her in the sacristy.

Marx and Bodie then spent some time being escorted through the hospital to Margaret Ann’s dorm room. They searched it, finding nothing unusual. Walking back downstairs, retracing Margaret Ann’s movements to the sacristy, Marx interviewed the Sisters of Mercy who knew Margaret Ann and had been on the scene when she was discovered.

Sister Madelyn Marie explained how she had found the altar cloth in the hallway outside and placed it on the pew where Bodie found it. Marx asked her why she thought Sister Margaret Ann had been raped. It was a good question, considering that was, after her scream, her first verbalization of what she had seen, or thought she had seen.

“I don’t know why I thought that,” she answered. “I assumed it from what I heard the others saying.” Then, in the kind of cold, unemotional prose common to police reports, Marx wrote, “Sister seemed to become upset…that it may have not been a man and that there may have not been a rape.”

“It could have been me,” she said suddenly. “I have big hands. I could have done it. But I was in my room until after it happened.”

Madelyn Marie was suddenly suggesting herself as a suspect? It didn’t make any sense. But she continued with that theme: maybe it was a woman and not a man who had killed Sister Margaret Ann.

“Did you know what they say about nuns? What they do together, when they are

alone

? They will say this is what caused the death.”

The sister was clearly implying some sexual link to the crime. None of the interview made any sense. Kathleen’s movements prior to the murder were easily accounted for. So why was she “copping” to a crime she clearly could not have committed?

There would be plenty of time afterward to analyze why someone implicates himself in a crime that he clearly could not have committed. The immediate goal was to catch Margaret Ann’s murderer. Toward that goal, Marx finished his interview with the nun and left the hospital. He drove to the county morgue and consulted with assistant coroner Dr. Renate Fazekas, who had been assigned to the case.

“She was strangled prior to the stabbing,” Fazekas told Marx in his preliminary report. Fazekas’s basis for this conclusion was “visible petechia on the face.” Petechia is small red or purple spots on the surface of the skin or mucous membranes as the result of tiny hemorrhages of blood vessels. When a person is strangled, petechia of the face is common.

“It appeared the victim was strangled from behind by an individual with large hands,” Fazekas also stated to Marx, who noted, “This was the doctor’s opinion due to the fact that a rather large bruise was noticed on the back of her neck.”

Fazekas, however, cautioned Marx that they couldn’t determine the cause of death until a complete autopsy was performed. That, of course, was and is SOP for coroners. As for sexual assault, it was impossible to be determined until the results of the rape kit came in and Margaret Ann’s body was completely examined. The rape kit consisted of vaginal swabs, oral swab, rectal swab, fingernail clippings from the left and right hands, hair samples from the skull and pubis, and a blood specimen from Margaret Ann.

The idea was to group and type the blood on each item, and then compare it to the blood taken from Margaret Ann’s body. Police forensic specialists would also attempt to determine the presence of sperm in Margaret Ann’s vagina, mouth, and/or rectum. Rape could easily be proven if any foreign fluid matched that of a suspect. The coroner would also attempt to determine if there was any flesh or blood under the nails of Margaret Ann that could be compared to the killer’s, if and when they caught him.

Fazekas opined to Marx that while it was uncertain until after autopsy how the victim died, it was the doctor’s opinion that the victim had probably been strangled prior to being stabbed. That’s why there was so little bleeding—when a person’s heart stops, she doesn’t bleed.

Marx left to continue his investigation.

As the new decade of the 1980s took shape, Toledo was going through profound social and economic changes.

With Japanese cars having successfully challenged and won the pockets of the American car-buying public with their superior products, cities like Toledo that relied on American auto factory employment for their livelihood saw production slow down. The city’s economy plunged.

The Diocese of Toledo was going through changes just like anything else. But one thing they still had were the go-to guys in the TPD. They were the staunch Catholic cops, like Sergeant John Connors, who were called by the diocese when someone charged a priest with sexually abusing a child in their care. That was when the tacit agreement between the TPD and the diocese to protect the priests so accused came into play. Suddenly any criminal charges against the pedophiliac priest would disappear as quickly as the diocese transferred the accused to some remote parish in the county.

None of this would become public until the

Toledo Blade

published an article on July 31, 2005, that said in part, “Over the past 50 years, those sworn to enforce the law and protect children repeatedly have aided and abetted the diocese in covering up sexual abuse by priests, a three-month investigation by

The Blade

shows.

“Beyond past revelations that the diocese quietly moved pedophile priests from parish to parish,

The Blade

investigation shows that at least once a decade—and often more—priests suspected of rape and molestation have been allowed by local authorities to escape the law.”

But this was 1980 and the agreement of concealment was still in place. Dr. Lincoln Vail was not a Catholic. He knew little about the religion. But that night, the night after the morning that Margaret Ann Pahl was murdered, he discussed the Swift Team call to the chapel with his wife, Colleen. He told her all about his encounter with the murdered nun.

Colleen took it all in. She had had psychiatric training. More importantly, she had common sense.

“Linc, someone on the inside did it,” she told her husband.

Margaret Ann Pahl had made a difference in life by serving her Lord. Now, in death, she had one more chance to make a difference by serving the state. While her soul was now with her Lord, her body was left on earth as a vessel of that spirit. In the hands of a good pathologist, a dead body can speak volumes. Dr. Renate Fazekas was good at his trade. His job was to help the Sister of Mercy solve a homicide—her own.

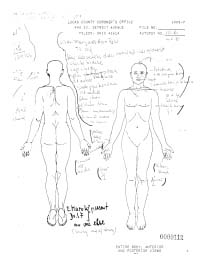

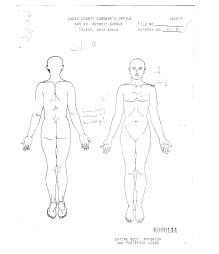

The morgue attendant placed her on the ME’s table. It was made of cold metal, with channels cut into it. Once the pathologist cut, the channels drained blood off quickly. Before getting to that, Fazekas started with an external examination of Margaret Ann’s body.

“The body is that of a 71 year old female weighing 134 pounds and measuring 62" in length,” Fazekas began, dictating into a tape recorder nearby. The tape would later be transcribed and turned into the official autopsy report that would be given to police. If a prosecution resulted, it would be introduced at trial as a prosecution exhibit. Fazekas proceeded with what should have been Margaret Ann’s last examination by a medical doctor.

“The body is dressed in a blue sleeveless dress. White blouse, blue under slip, white bra, pantyhose, girdle pants, and blue shoes. Pantyhose and girdle pants are gathered around the ankles. A black veil accompanies the body.

“A silver-colored necklace, with a [silver] cross attached is around the neck. A [silver] cross is pinned to the left side of the dress. A silver colored ring is on the 4th finger. Rigidity has not yet developed. Lividity was absent.”

Livor mortis or postmortem lividity occurs after death. Blood settles in the lower part of the body, causing a red/purple skin discoloration. Parts of the body in contact with the ground or something else do not show this discoloration, however, because the capillaries are compressed. Lividity being absent on Margaret Ann’s body confirmed that she was a “fresh kill,” meaning evidence was recent and had not yet deteriorated.

“A 3½" long oblique scar is over the right lower abdomen.”

It was an appendectomy scar. Someplace along the line, Margaret Ann had appendicitis and had to get the useless vestige of an organ removed.

“A 1½" long oblique scar is over the medial aspect of the left knee.”

Margaret Ann had had an operation to repair the medial ligament of the left knee.

“The teeth are natural.”

Suddenly, Fazekas changed direction.

“The body is involved with multiple stab wounds and evidence of strangulation. There are six stabs wounds to the left side of the face. The stab wounds are transverse and oblique [author’s note: remember this for later] over the left angle of the mouth and just below the left side of the jaw. The deepest penetration measures 1½",” he dictated.

This was not only major damage, it was major rage. The killer had stabbed the nun so hard, he had gone through the skin of the mouth and into Margaret Ann’s jawbone.

“There are fifteen transverse and slightly oblique stab wounds to the left aspect of the neck. The direction of the stab wounds is from front to back. The deepest penetration measures 3".”

Because of the obvious similarities, the ME opined they had been made by the same, unknown instrument.

“There are nine transverse and oblique stab wounds to the left side of the chest, between the left clavicle and nipple line. Two of the stab wounds range in size from

1

/8" to ½" in length. They are similar to the above described stab wounds. Some have a slightly irregular outline. The direction of the stab wound is front to back. The deepest penetration measures 3".”

Three inches may not sound like much, but in the case of Margaret Ann Pahl’s chest, that meant the sharp instrument penetrated through her chest cavity, right into her heart. If it hadn’t stopped beating by then, it most certainly would have immediately. Perhaps it was the very brutality of the crime that caused the ME to miss the most important evidence of Margaret Ann’s murder. It was staring him right in the face.

Fazekas’s autopsy photographs and diagrams show that the nine stab wounds over Margaret Ann’s heart formed the pattern of a cross, tilted slightly to the left. In deference to the ME, the cops had missed it too, and the reason is simple. Who could imagine a priest killing a human being, let alone doing so in such a ritualistic way? It didn’t make any sense. Murder never does, but this case was setting a new standard for the unbelievable.

With his external examination complete, Fazekas made the classic pathologist’s “Y” incision down the body to examine her internally. Only then would he know the damage that the stabbings had done to her organs.

“The left common carotid artery reveals a rent at the cranial segment. The larynx and trachea reveal three stab wounds. The esophagus is perforated one time. The fourth and fifth cervical vertebrae [in the neck] are each involved with a stab wound. The entire anterior and lateral neck is hemorrhagic.”

She had been stabbed hard enough not only to perforate parts of the throat and organs, but some of the stabbings had been hard enough to go through skin, into the spine, and take out two vertebrae. That alone would paralyze someone for life.

“Her left lung had been stabbed twice,” the ME continued, “the sternum contains stab wound at the level of the third inner costal space, which extends through the right ventricle, just below the cusps of the pulmonary valve.”

The killer got her right in the heart.

Under a section entitled “Evidence of Strangulation,” the ME wrote, “Numerous distinct petechias involve the conjunctive of both upper and lower eyelids and the face with the exception of the forehead. Both supra and infraclavicular areas are recently bruised (blue). The area measures 10" x 4". An oblique linear bruise, outlining the necklace, is over the right supra and infraclavicular area.”

Margaret Ann had been strangled by

something,

probably large hands that had left the imprint of her necklace in her skin. The assault resulted in a classic symptom of strangulation, the “distinct petechia” or broken blood vessels in the upper face. To finally make the point, the ME concluded:

“Both cornu of the hyoid bone are fractured. The fracture sites are surrounded by hemorrhage.”

In a classic strangulation, the hyoid bone of the throat is broken by the killer’s increasing and persistent pressure on the throat. This guy had fractured the hyoid bone in two places. Fazekas also noted something else important.

“A 3½" x 2" recent bruise prominently involves the bonily prominent area of the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine, slightly to the right. Within the area are three parallel longitudinal, linear bruises, each measuring 2" in length.”

What the ME was describing were inner thigh bruises symptomatic of rape. The rape kit results had also come back as follows:

MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION:

DEEP VAGINAL SMEAR:

No sperms identified.

VAGINAL SMEAR:

No sperms identified.

ORAL SMEAR

No sperms identified.

RECTAL SMEAR:

No sperms identified.

That pretty much cinched it as a circumstantial case. If the killer had raped her with his penis, it was sheathed. Regardless, there was a complete lack of semen with which to type her assailant. It was possible she had been penetrated by an object other than a penis, but there was nothing inside her vagina, her mouth, or her anus to indicate forced penetration by any sort of object.

In his concluding “Diagnosis,” the last one Margaret Ann Pahl would ever get from a doctor, Dr. Fazekas wrote, “Multiple stab wounds (31) to left side of the face, neck and chest, strangulation.

“Opinion:

This 71-year-old white female, Sister Margaret Ann Pahl, died of multiple stab wounds to the left side of the face, neck and the chest. There also was evidence of strangulation.”

Fazekas was

not

saying she had died from strangulation. Clearly, she was alive when she was stabbed repeatedly. If she wasn’t alive, she wouldn’t have bled. The stab wounds provided the immediate cause of death. It was the pattern of those stab wounds, not yet detected, that created the most mystery. While it was possible that the cross-shaped pattern of the chest wounds was a chance rather than deliberate occurrence, if you added the altar cloth into the equation, things certainly did get interesting.

Would the killer place the altar cloth over Margaret Ann’s chest

by chance

, and then stab her

by chance

in the shape of a cross? Oh, and the killer stabbed her in the sacristy

by chance

on the only day of the year the

consecrated Host

, the body and the blood of Jesus, is there watching the murder from nearby? The mere fact the killer clearly took his time, did his business in a very secluded place, and slipped away without being caught showed that he knew what he was doing and where he was doing it. He could not have escaped without detection had he not known the ins and outs of the hospital and specifically the chapel and its adjacent areas. He was so confident, he left the lights on behind him; he wanted Margaret Ann discovered the way he had left her.

Margaret Ann had either been the victim of some sort of bizarre ritual killing, or the killer was trying to make it

seem

that way to divert attention from him. If the conclusion was the latter, then this was a very clever killer indeed, someone not only capable of eluding detection, but using the public’s popular fascination with ritual killing to get away with murder.

With the autopsy completed, the TPD released the body for burial. It was transported to a funeral parlor in Fremont, Ohio, where Margaret Ann was prepared for her final rest. The undertaker drained her body of blood and filled her veins with embalming fluid. Her body was then cleaned up and placed in a habit that her order provided. Finally, the undertaker placed Margaret Ann in a nice wooden coffin.

April 9, 1980

The last time Fremont, Ohio, had been in the news was in 1893, when former president Rutherford B. Hayes died at his Fremont home, Spiegel Grove. Hayes’s estate, which included his tomb, was just blocks from St. Bernardine Chapel.

The first time they buried Margaret Ann Pahl, it was as if God was angry. Ominous black clouds appeared overhead. Everyone who was there would remember later that the winds blew hard, pounding at the doors of the chapel. Inside, it was time to say good-bye. During a Catholic funeral, the Church “commends the dead to God’s merciful love and pleads for the forgiveness of their sins.” Through the funeral rites, Christians “offer worship, praise, and thanksgiving to God for the gift of a life which has now been returned to God, the author of life and the hope of the just.”

In the Church’s book of ritual

The Order of Christian Funerals,

the first of the three principal components to a Catholic funeral is the vigil for the deceased, sometimes referred to as the “wake.” It is held at the funeral home or the church. This had already taken place. Most importantly for Margaret Ann Pahl’s right to finally be laid to rest, the casket, with the lid closed, had already been placed in the front of the chapel for the second component, the funeral liturgy.