When Satan Wore a Cross (9 page)

Holy shit, it worked,

Davison thought.

They don’t even know who I am!

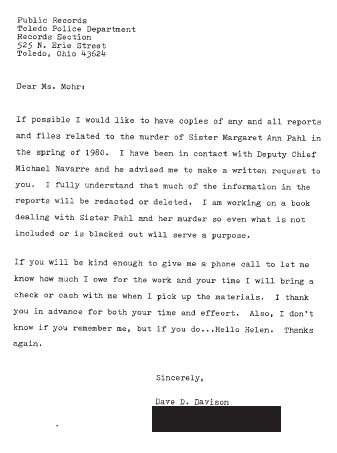

Anxiously, he sat down to write his next letter:

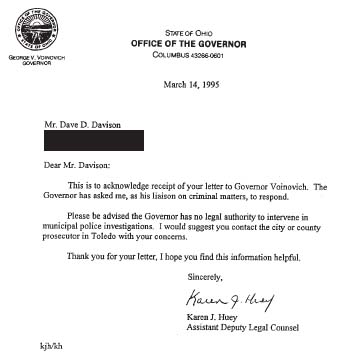

While waiting for a response, Davison next wrote to Ohio governor George Voinovich about the case and the way the TPD had handled it. The governor’s response?

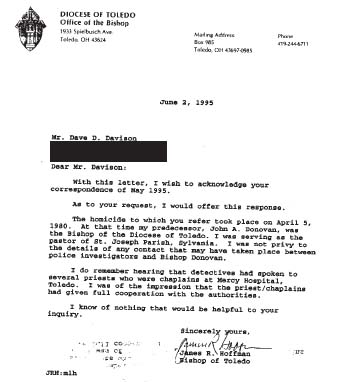

Voinovich was the governor. He could certainly ask the state prosecutor, the Ohio state attorney general, to look into the matter and report back to him. Instead, Davison got a brush-off letter that defied common sense. Next, Davison wrote the bishop of the Toledo Diocese who had replaced Donovan, James R. Hoffman. He asked Hoffman for assistance in investigating Sister Margaret Ann Pahl’s unsolved murder. The bishop responded personally:

Under Vatican edict, every diocese maintains a secret archive that contains top-secret information on all priestly activity within the diocese. Hoffman knew this, though no one else outside the church did at the time. Hoffman could have opened those records to Davison. It was an unsolved homicide of a nun within Hoffman’s diocese. Instead, Hoffman chose to ignore Davison’s request. Less than two years later, Bishop Hoffman would relieve Father Robinson of his duties at St. Vincent de Paul.

Davison had the patience of a saint. If he hadn’t been imitating Don Quixote tilting at windmills before, he certainly did with his next letter. He sent it to the Pope John Paul II, care of the Vatican, informing him of the unsolved 1980 murder of a sister of the Roman Catholic Church in Toledo—the Pope was Polish and sure to know the parish’s history—and the fact,

the fact,

that

a priest

of that same church had been the prime suspect in the unsolved homicide.

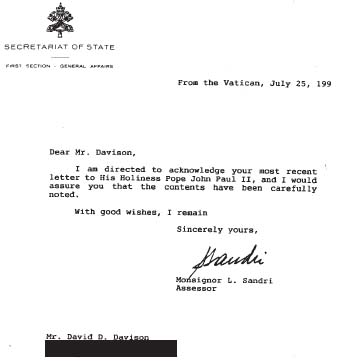

The response came swiftly:

While the letter appeared to be another brush-off, it had found its way to the right party.

Another distinguished member of the monsignori, L. Sandri was a church assessor. According to the

Catholic Encyclopedia

, the title of assessor has a twofold meaning. The assessor can be a judge in a collegiate tribunal or one who assists the presiding judge in interpreting the law. “In the latter meaning assessors are simply advisers of the judge, who aid him to obtain a full knowledge of the case and by their advice, helping him to decide justly.”

Assessor Sandri’s interpretation seemed to be that no further Vatican action was warranted in the case. The Vatican never contacted Davison again. Pope John Paul II probably never knew of the charges in the one diocese in the United States where he surely had to feel at home. It would be hard to believe that the pope of the Roman Catholic Church would ever be content to let the murder of one of the church’s most devoted servants, a nun, go unsolved simply because a priest was implicated.

Then the phone rang. Davison picked it up.

“Hello, this is Sonja McMahon down in records. I have your FOIA request and I’ve got three hundred pages of documents for you. When can you come pick it up, and bring your checkbook?”

Davison couldn’t believe it! Had his bluff actually worked?

“I had a friend who did the FOIA requests,” Davison says. “To this day, I think she did me a favor.”

He ran down to the second floor of the Records Bureau downtown. There was a bounce to his step that hadn’t been there for fifteen years. In the corner closest to the municipal court across the street was a large office. Davison opened the door into a huge room, where about twenty people sat at desks. They were the custodians of the records of the TPD.

“This lady brought the stuff up to me. It was flapping loose,” Davison says. “I took it home and went through it, outlining in colored marker the sections I thought were most relevant to the case.”

Ray Vetter’s hubris perhaps made him think that he had gotten all the copies of the reports on the Pahl homicide. He hadn’t. Someone had held out. The three hundred pages of police reports covered much of the initial investigation. But every mention of Robinson as the prime suspect was either blacked out or purged completely. That included Davison’s own supplemental reports with the people on the scene who implicated Robinson as the prime suspect.

Some of the censoring had been done very poorly by someone who wasn’t very bright. Many pages contained enough detailed descriptions of persons and events to make them clearly identifiable, no matter that names were blacked out. Taken all together, the reports showed a textbook homicide investigation cut short at the point that Robinson became the prime suspect.

The papers were notable for what they didn’t contain: the results of the autopsy of Margaret Ann Pahl. Davison made another FOIA request for the autopsy report. But it was too late.

“They figured out what was happening. They lied to me,” Davison claimed. ”The records people told me that the case had been reactivated. They said that the case had been given to Lieutenant Gary Lockwood, who was currently investigating. I didn’t get anything else.”

According to Davison, Lucas County prosecutor Anthony Pizza found out what had happened. Buying the “con” that Davison was writing a true crime book, he told the retired cop that he better prove his charges of a police cover-up in his book or they’d sue him and own him. Davison didn’t mind. There wasn’t much he owned but his neat little house. Inside of course was a different matter.

Dave Davison is an animal nut. He has four dogs rescued from the Toledo Humane Society; six birds, most of which he got from people who died and the animals had nowhere to go; two turtles and four frogs, all found in his yard over the years; one very large spider from Mexico; and finally five lizards, most of which were given to him when their owners got tired of them.

“In truth I cut myself off from people because I came to the conclusion I preferred animals to people,” he says.

It’s a good thing he has a cop’s pension, otherwise his animals would starve. Now, if they went after his animals,

that

would be a different story.

For now, Dave Davison was content to hoard the documents. He had tried as hard as he could to get someone outside Toledo interested enough in the case that they would push it through to its conclusion. That had not happened. Davison was realistic enough to know that while things weren’t working to his benefit now, that didn’t mean in five or ten years, there might not be an opportunity to prosecute the son-of-a-bitch.

Dave Davison settled down to wait. As long as it took, he was intent on getting “Father Jerry” for murder.

Suddenly, it was June 1692 in damp Salem, Massachusetts. Innocent people were being accused of satanic abuse. Only it wasn’t. It was August 1983 in beautiful, sunny Southern California.

In the Los Angeles suburb by the sea, Manhattan Beach, seventy-nine-year-old Virginia McMartin, fifty-nine-year-old Peggy Buckey, and her twenty-eight-year-old son Ray Buckey were accused by the mother of one of their preschoolers of sexually abusing and torturing children in satanic rites at their Manhattan Beach day care center. It was about as bizarre a story as any to come down the crime pike.

The prosecutor, the L.A. District Attorney’s Office, relentlessly pursued the accused. The case snowballed as outside “experts” counseled most of the children at the day care center into believing they had all been victimized. That led to the DA charging the defendants and bringing them to trial twice in 1989 and 1990, for sexually abusing the children under their care. Both of the trials ended in hung juries. After the second trial, Los Angeles DA Ira Reiner wisely dropped all charges.

The McMartin Preschool abuse trials turned out to be the longest and most expensive criminal trials in American history. Fueled by the baseless charges of a woman who it turned out had emotional problems, the elected representative of the citizens of Los Angeles County had spent seven years of taxpayers’ time and $15 million of their money investigating and prosecuting a case without any convictions. When it was all over, the victims were twofold: the kids who had implanted memories of satanic sexual abuse by the so-called experts, and the defendants whose lives and careers were ruined by the baseless charges. Ray Buckey spent five years in jail without bail, waiting for the trial.

But people in California and the rest of the country were only too ready to believe the satanic charges they heard during the McMartin Preschool trials. The media diligently complied, following every turn of the trials and sensationalizing them whenever they could, which only served to obscure the truth—a national epidemic of satanic abuse cases began to be reported. From coast to coast, stories emerged of children being beaten, sexually abused, tortured, and in some instances, used as human sacrifices by satanic cults.

Hard evidence being at a premium, most if not all of these cases would eventually prove to be specious. That made no difference. A conservative social climate swept through the United States in the 1980s, where people were wont to believe the worst in their neighbors. The same thing had happened in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692.

The Salem witch hunt murders started when a West Indian slave called Tituba performed magic tricks for the daughters of Samuel Parris, pastor of Salem Village. Eventually, the circle for which she performed widened to include other curious friends. But Tituba’s magic had the curious effect of making some of the girls act irrationally.

A local doctor was called to treat the young women. A doctor in 1692 really was worse than no doctor at all. Dr. Staunch Protestant White Guy pronounced the girls bewitched. That made it a clerical matter. The girls were intensely questioned by the town’s clerics. When asked who had bewitched them, they accused Tituba “and two derelict women in the community.”

That made sense: accuse the disenfranchised rather than the privileged. All three were arrested. Some sort of archaic good cop/bad cop questioning followed during which Tituba, seeing the proverbial handwriting on the wall, informed on the other two. She got off. The other two hanged.

They had been condemned by a hastily put together court of attainder that had no legal authority. Despite that, from then on, anyone could be accused of being a witch in Salem and executed. When it was finally over, a total of twenty people lost their lives as a result of the state-sponsored Salem witch trials.

In 1985, the satanic cult hysteria that had swept the country found its way into Toledo, that backward pocket of civilization on Lake Erie. A Toledo resident told the police that he had been a member of a satanic cult operating in the greater Toledo area. The cult was responsible for the deaths of sixty to seventy-five infants, children, and adults. The charges sounded outrageous but Deputy Sheriff James Telb, Lucas County Sheriff’s Department, took them seriously.

As anyone of a later generation who has watched

The Sopranos

knows, getting rid of a dead body is not an easy thing. It’s the same in reality. Where do you put so many bodies? Do you dig graves? Ever try to dig seventy-five graves deep enough so the bodies aren’t discovered? Seventy-five holes, even smaller ones for the kids, would be impossible to keep secret.

Or maybe you decide to cut them up. Ever try cutting up seventy-five bodies? Lot of blood. That’s a lot of evidence. Luminol can illuminate the most microscopic traces of blood. Distributing body parts from seventy-five bodies is also not an easy thing. Then again, how about burning the bodies during a satanic rite? One problem: you could never get the fire hot enough outdoors or indoors to completely burn the bodies. Unless you used a professional crematorium, bones and other organic matter would be left for identification.

Telb followed up the complaint by leading a dig at three sites in Spencer Township, a Toledo suburb west of the city. Quickly, the three sites of alleged satanic sacrifice were excavated in twenty-four hours. Deputy Sheriff Telb told the

Chronicle-Telegram

newspaper, “Artifacts [discovered] included two large knives, a doll with its feet nailed to a board and a pentagram medal tied to its wrist, wooden crosses, and red twine wound through bushes and grass around the three excavation sites.”

A reporter for the

Columbus Post Dispatch

dryly observed, “Hanging from a tree branch next to a rural Lucas County road was what for all the world appeared to be a piece of red string, perhaps six inches long. It wasn’t knotted or arranged in any way. It just hung there about eye level, waiting for the wind to carry it to the ground or for an expert on Satanism to call it a tool of devil worship and possible evidence of ritual murders.”

Deputy Sheriff Telb insistently told the same newspaper on June 22, 1985, “We know there’s a cult here. There’s no question there’s a cult operating in Lucas County. We found enough evidence here to substantiate that.”

If they did, nothing ever came of it. The national media that had converged on Toledo to cover the “Lucas County incident,” slowly dispersed to tackle the next story of national insignificance. Then TV took it a step further. People labeling themselves as “Survivors of Satanic Cults!” appeared on trashy daytime talk shows. The ratings on these freak shows soared through the late 1980s and into the middle 1990s.

By 1995 the truth was starting to be known. A national scandal had erupted in the therapeutic community. So-called therapists, many with nothing more than a one-year master’s in social work, had implanted memories in their patients’ psyches. They had encouraged them to believe they had been satanically abused when they had not. Lawsuits and settlements followed. Then, with the dawn of the millennium, reports of satanic cults died away, to be replaced by reports of priests sexually abusing minors in their care.

Beginning in 2001, priestly sexual abuse scandals rocked the Catholic Church. This time, there was hard evidence that could not be refuted. After decades of covering up for pedophiliac priests, the Church had finally wised up long after rank-and-file Catholics did. Even the most devout Catholics had long ago discovered that the saintly and chaste Father O’Malley and the grouchy and chaste Father Fitzgibbon were Hollywood creations. Across the United States in parish after parish, priests were accused of sexually abusing minors in their care.

The first clerical sexual abuse scandal to hit Toledo during this period involved the Oblates priest, Father Chet Warren. Back in 1993 eight women had come forward with credible evidence of clerical abuse by Father Warren. The Toledo Diocese realized the charges were probably true. They did what parishes around the country had started to do in similar circumstances: they made a deal for the priest to quietly leave the priesthood. Warren was defrocked.

One of Warren’s alleged childhood victims, Teresa Bombrys, had moved to Columbus. In 2002, forty-four-year-old Brombrys sued Warren, the Oblates, and the Toledo Diocese for damages relating to her alleged abuse at Warren’s hands and other parts of his body. The story was covered in the

Toledo Blade,

where a now adult Marlo Damon read it. Damon started to sweat and have flashbacks to her abuse. She knew Chet Warren intimately.

Marlo Damon had never voiced her claims of childhood satanic abuse by her father and his cult of Satan worshippers, including Warren and the Catholic priests of the Toledo Diocese. Despite her trauma, she had grown up to become an important member of society—a nun. Though she didn’t know it, Sister Marlo Damon and Sister Margaret Ann Pahl had much in common. In some strange way, they were connected though they never met and were certainly not related. When they did eventually come together, some would look at one as being the savior of the other.

Damon served her Lord as one of the Sisters of the Cathedral, an order founded by Emelie Starker in Hungary, 1894. Since then the order has grown to a thirty-two-hundred-member international congregation on four continents, divided into geographic units called segments. With the mother house based in Rome, there are five segments in the United States including Toledo, where the sisters have been ministering to the poor since 1899.

As a devout Catholic, becoming a nun was a way for Damon to fight back against her childhood abuse. In some ways, it might have been her only choice.

Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition,

Section II, The Fall of the Angels, speaks eloquently of who is the real enemy of Catholics.

“Behind the disobedient choice of our first parents lurks a seductive voice, opposed to God, which makes them fall into death out of envy. Scripture and the Church’s Tradition see in this being a fallen angel, called ‘Satan’ or the ‘devil.’ The Church teaches that Satan was at first a good angel, made by God: ‘The devil and the other demons were indeed created naturally good by God, but they became evil by their own doing.’”

In choosing to serve her Lord, Jesus Christ, Damon was choosing to fight the one Jesus called “‘a murderer from the beginning,’ who would even try to divert Jesus from the mission received from his Father. ‘The reason the Son of God appeared was to destroy the works of the devil.’”

Satan was behind her abuse. Satan needed to be fought, and defeated.

“It is a great mystery that providence should permit diabolical activity, but ‘we know that in everything God works for good with those who love him.’”

In 2002, Sister Marlo Damon wasn’t questioning God. Not at all. What she was questioning was why she had to keep shelling out for expensive psychotherapy. It really didn’t make much sense. Shouldn’t those ultimately responsible for the actions of the priests who she says abused her be the ones who paid? With all the attention the public and media had given the cases of priestly pedophilia, wasn’t it right that the same attention be paid to the satanic abuse she had described? It was a perfectly logical argument.

While Sister Marlo Damon was going through this self-questioning process, she had flashbacks to her satanic abuse sessions. Simultaneously, the Church was having its own problems with flashbacks. The Vatican finally figured out that whatever policy they had in place to take care of clerical abuse just wasn’t cutting it. They needed to deal with the problem or face further defections from the ranks of practicing Catholics.

In 2002, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops held a convocation in Dallas, Texas. The document all the bishops agreed to came to be known as the Dallas Charter. The church refers to it formally as the

Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People.

Primarily, it is a mea culpa for all the cases of priestly abuse.

“The Church in the United States is experiencing a crisis without precedent in our times. The sexual abuse of children and young people by some priests and bishops and the ways in which bishops have addressed these crimes and sins, have caused enormous pain, anger and confusion. Innocent victims and their families have suffered terribly.”

Then came the confession.

“In the past,” the charter preamble continued, “secrecy has created an atmosphere that has inhibited the healing process and in some cases enabled sexually abusive behavior to be repeated. As bishops we acknowledge our mistakes and our role in that suffering, and we apologize and take responsibility for too often failing victims and our people in the past. We also take responsibility in dealing with this problem strongly, consistently, and effectively in the future. From the depths of our hearts we bishops express great sorrow and profound regret for what the Catholic people are enduring.”

It was an astonishing document and if carried through to its logical conclusion, could revolutionize the way the church dealt with clerical abuse cases. Most importantly, to advance the promises to protect children, dioceses in every state would set up internal review boards to hear victims’ allegations and make recommendations on how to proceed.

Sister Marlo Damon took the charter seriously. Being a good nun, she believed in the system in which she served, that she could get justice from it without going to an outside body. Therapy had given her value as a person. That’s why she was angry.

Why should she have to continue paying for what those people had done to her? She had no money; she had taken a vow of poverty. Like all nuns, she was given only a pittance to live on. It was out of those meager funds that she saved for her therapy. Her order had helped with her bills, but they were tapped out. The financial burden was crushing.

Sister Marlo Damon believed in her Church, she believed in the Dallas Charter, she believed in her order, and she believed in the Toledo Diocese. After all, Sister Marlo Damon reasoned, she had God on her side. He was with her when she picked up the phone and called Frank DiLallo. Frank DiLallo was the diocese’s case manager. Damon asked for a meeting, to which DiLallo agreed.