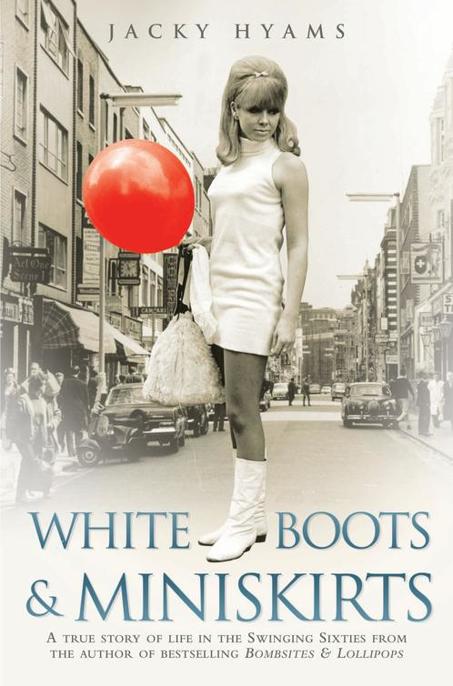

White Boots & Miniskirts

Read White Boots & Miniskirts Online

Authors: Jacky Hyams

WHITE BOOTS

& MINISKIRTS

A

TRUE

STORY

OF

LIFE

IN

THE

S

WINGING

S

IXTIES

FROM

THE

AUTHOR

OF

BESTSELLING

B

OMBSITES

&

L

OLLIPOPS

JACKY HYAMS

To Ron, Clive and Ian.

Gone too soon. But not forgotten.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 THE COMPLAINTS MANAGER

CHAPTER 2 A SECRET TRIP ON THE CENTRAL LINE

CHAPTER 3 RANDY SANDY AND THE CHICKENS

CHAPTER 4 THE GO-GO GIRL FROM GUILDFORD

CHAPTER 9 MR VERY, VERY DANGEROUS

CHAPTER 11 THE SPY WHO LOVED ME

CHAPTER 12 MANY RIVERS TO CROSS

M

y sincere thanks to the usual suspects, fellow writers Tammy Cohen, for her unfailing support and insight, and John Parrish in Sydney, whose enthusiasm for my ideas never fails to encourage me.

All thanks also go to Alice Jordan (for showing me that the life of a 20-something woman hasn’t changed that much!) and to Mary Bowen, my Melbourne

consigliere

, always up for consultation – and excellent advice.

Gratitude too to Jenny Wright and Jeff Samuels, former news desk inmates whose memories of those times proved invaluable.

Finally, a big thank you to the British Library team at Colindale, unfailingly courteous and polite, no matter how minor the request.

T

he country was going to the dogs. Optimism was in short supply. The economy was in a perilous place. Money was tight. Upheaval on the streets. House price crash. Terrorism. And unemployment on the rise…

Welcome to Britain. Go on, fill in the year. Some time in the early 21st century, perhaps? Yes and no. Because our history is dotted with similar patches of extreme uncertainty when the only way through seems to be to either just get on with it – somehow – or get out, jump on a plane, find a better way of life… Back in 1976, when I decided to do just that, the country was pretty much locked into a negative spiral: the general belief was that Britain had a dismal future.

Yet just ten years before, the sun shone down on Blighty and the streets were full of partying people: the summer’s World Cup soccer victory over Germany at

Wembley in 1966 seemed to set the seal on what looked like a golden age of optimism. Mini-skirted London was widely acknowledged as the swinging city. An unprecedented explosion of Brit creativity had made a huge impact all over the world. Our musicians, designers, pop and movie stars were fast becoming international icons. Youth culture was big news, on the march, especially across the Atlantic.

The older, wartime generation might have blinked, rubbed their eyes at all these long hair and free love ideas that were being spouted, let alone the idea of their kids hitting the hippie trail to the East or smoking pot, but these were stable times: jobs for nearly everyone, less than a quarter of a million people unemployed in that year of World Cup jubilation. Foreign holidays in the sun had started to become a national pastime. And colour telly was on its way.

When I sat down in 2011 to write my 1950s East End memoir of my childhood,

Bombsites and Lollipops

, I wrote not just about myself, my parents, my teenage adventures, but about the world I’d inhabited, one of a society – and a city – shaking off the lingering effect and deprivations of wartime and very slowly reinventing itself into something approaching what we know today. I had hoped, of course, that readers could identify with some of it or that if the world described was unfamiliar, even alien, they’d find something entertaining in the reminiscence of the ‘lost world’.

Much to my delight, they did. The response was immensely gratifying. A writer always hopes to strike the right chord, but you never really know if you’ve hit the right note until you get the feedback from your readers. Among all the welcome positive feedback, I kept getting the same comments, time and time again: ‘So what happened next?’, ‘How did you get from there to here?’, ‘I didn’t want it to end’. And so on. Hence my decision to write a sequel, covering another lost world, the decade after that book ended, when I’d first left home and started to make my way in life.

The changes in my own life were gradual. But in some ways, they were reflections of the big social changes around me. And the mood of the country itself shifted quite quickly: from chirpy to bleak within a few years. In the summer of 1966, anything seemed possible, the future looked good. Yet even by 1970, the storm clouds were already gathering. Everyday lives were changing for the good, more people travelled abroad, wages were good and though it was early days, the arrival of the supermarket and the home ownership culture were already making an impact. Yet from then on, industrial disputes, strikes, shortages and inflationary woes were to continuously plunge the country into crisis mode through the decade.

The ’60s – the sex, drugs and rock’n’roll years – are always viewed as the pivotal moment, the starting gun, if you like, of massive change in British society. Technically,

this was true. Yet a lot of it was mostly hype: the much-touted sexual revolution, at least, didn’t actually happen for most people until the ’70s arrived. And the politics of the time, from Harold Wilson’s rocky Labour era of 1964-70 to the false dawn of the Conservative ‘Better times ahead’ Ted Heath years that followed, eventually took the country down a bitterly acrimonious path of union confrontation and IRA terrorist carnage. If the ’60s seemed like the best of times, the decade that followed surely would seem the worst of times.

That extraordinary decade followed the years of my youth. The immediate post- WWII generation were late starters by today’s standards. We lost our virginity in our late teens, maybe later. We emerged from the late ’50s as the first wave of youthful consumers, even though, as teenagers, we hardly knew what consumerism signified. For those like me, abandoning education at 16, it could be said that our university years were the march straight into the adult working world. Through work, you meet people. Move around all the time from job to job, as I did, and you meet many more, learning as you go, not just about offices but about life. Constant exposure to lots of different people from many different backgrounds hadn’t always been the common experience for working class girls – until the class barriers started to wobble in the ’60s.

I was a rebel, in that I wanted to throw off my East End background and didn’t accept the general status quo: that

a young girl best sit tight and hang on for Mr Right. Yet I wasn’t in any way political in my thinking. My ideas about freedom and free love weren’t feminist as such. I didn’t go on marches or protest on the streets. I didn’t consciously believe women’s lot was unfair. Certainly, I questioned what I’d been told since childhood, mainly because a lot of it didn’t make sense to me. Fortunately, I was single-minded in my determination to reject all this by getting out there, sharing flats, though without real economic independence, the very thing I craved, this didn’t always prove to be a successful venture. How could it be? I wasn’t an educated thinker. I operated on instinct alone, an ordinary 20-something from a challenging background at a time when women were just starting to be unshackled from the many things that had always held them back: fear of unwanted pregnancy, outdated laws around divorce, economic restraint. For me, it was all about having my freedom.

Around the time my story starts, a single mum was in a bad place as far as the rest of the world was concerned. Some men still believed they had to tell a woman they loved her in order to convince her it was OK to have sex. Yet by 1976, ‘I love you’ was frequently being replaced by ‘What was your name again?’ the morning after. Or ‘I divorce you’. By then, anyone landing from a distant planet could have easily wondered if many of the inhabitants of these islands had anything else on their mind other than sex. Or hedonism.

Working lives changed a lot too in that decade. In 1966, most men preferred to have stay-at-home wives. Ten years on, a woman’s work or part-time job to supplement the household income, help pay the bills to raise their family, was more or less taken for granted. My belief too is that in this transitional decade, younger people, at least, became much more worldly in outlook. The cheap travel had a lot to do with that. The ’70s kick started the real changes in what we ate back home too, reflected by the many Chinese, Italian, Indian and Greek restaurants that started to pop up on our streets. Whether we liked it or not (and many did not) the switch to a decimal currency followed by Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973 shifted our general perspective a notch, forced us to look outwards.

This is, of course, a personal story. It’s about my own experiences and what was going on around me. London is a huge, sprawling city: very much a series of villages and my personal village had distinct borders. It encompassed my parents’ home in Dalston, central London, the West End, Fleet Street and the leafier parts of north-west London. It certainly wasn’t suburbia. But what is interesting about it in historical terms, if you like, is that many of those streets and places where the story took place remain just as they were.

Fleet Street, of course, has vanished in that it’s no longer a thoroughfare hosting most of the country’s

national newspapers, but an extension of the financial and legal district, though a few of the ancient pubs still remain as testament to journalism’s long lamented pub culture. The huge

Mirror

building where I worked, the proud, bustling enterprise which dominated the area around Holborn and Chancery Lane for so many years, is gone, the site transformed into Sainsbury’s head office. Which probably speaks volumes about the changes to our way of life. And there are the areas around Hackney and Dalston: left virtually untouched for several decades, they’re now dramatically changed by a wave of gentrification, infrastructure and fashionable development, something that was unimaginable in the shabby, scruffy ’70s.

The music was there all the time, too. Originally an Elvis girl, I remained loyal. For life. Yet what followed Elvis musically became such a phenomenon – I defy anyone around in 1967 not to remember where they were or what they were doing the first time they heard the

Sgt Pepper’s

… album. The music resonates still. The wonderful thing about it is we can now access it instantly, with a touch of a button or a single swipe. If anything, the music takes on an even greater significance the more time passes. It was that good: listen to it now and marvel at the extraordinary talent that produced it. Yet at the time, for me, it was just… taken for granted. Like all the other exciting things that were happening around us.

There are places in my memory where the detail is somewhat cloudy (this book does start in the ’60s, after all). So I trust I’ll be forgiven for that. Some names have been changed too. My single regret in this is that I didn’t write it all down at the time. But here, at least, are some of the highs and lows of those times remembered. We laughed a lot, drank and smoked too much, slept too little and lived, mostly, for the next party. Or holiday in the sun. It might have been almost half a century ago. Yet the carefree, often reckless insouciance of youth never changes. Mine was definitely prolonged by my refusal to take responsibility for anything. Yet for that, I am now truly grateful. There was time enough ahead to sober up and start living sensibly.

I like to regard that 1960s–70s decade as the era when many of us happily followed the hedonistic ‘Have a good time – all of the time’ mantra (as put so eloquently in the rock’n’roll movie

This is Spinal Tap

).

Though of course you can, if you wish, use those words as a motto for life…

Jacky Hyams

London, February 2013

THE STORY SO FAR

In my previous book

Bombsites and Lollipops

, I told the story of my childhood, growing up in post-WW2 Hackney in one of London’s most deprived, bomb scarred areas in the East End. With my parents, Molly and Ginger, I inhabited a bizarre world. We lived in squalid, depressing surroundings: a tiny, damp flat in a narrow alleyway dotted with bombsites and ruined buildings. Poverty was all around us in the 1950s, yet we lived like kings. While most of the country skimped and saved, struggling to live on meagre rations, enduring freezing winters, fuel shortages and power cuts, we ate the very best food available, wore beautiful clothes, had an army of servants and helpers – including a cleaner and a chauffeur – and my parents stepped out frequently, living the high life in London’s West End or partying with London’s most notorious duo: the Kray Twins.