Who Made Stevie Crye? (24 page)

Read Who Made Stevie Crye? Online

Authors: Michael Bishop

Tags: #Fiction, #science fiction, #General

Cathinka did not know how to respond. She remembered that Don Ignacio’s cardinal stipulation about her wishes was that none of them violate her wedding vows. She could not succumb to Waldemar’s blandishments without breaking her word, for her lover had come to her as a direct result of her second wish. To lie with him would be to lie in an even more damning respect.

Yet she wished to lie with him. The Tropic of Cancer had worked its amorous metastasis in her blood, and Waldemar’s every breath was a provocation as lyrical as a poem. Cathinka began to think, to think, to think. She and Don Ignacio had never consummated their marriage. That being so, perhaps she could not be unfaithful to him by disporting her still unfulfilled flesh. . . .

Someone knocked on her door. Waldemar, of course. (The monkeys never came to her of their own accord.) She bade him enter. His pale eyes were blazing like fractured diamonds. He took her by the shoulders and pressed his case with his body rather than with passionate arguments. Cathinka broke away, and he stared at her panting like a spaniel. She was panting herself. A comatose monkey in a canoe was denying her the one boon she most desired, a commingling of essences, both spiritual and carnal, with Waldemar. What an absurd and demoralizing standoff the little beast had executed.

“Today, Cathinka,” Waldemar told her, “chastity does not warrant so rigorous a defense.”

“My chastity is not the question,” she replied, bracing herself against her writing stand. Not to mock Waldemar’s intelligence, she refrained from stating the true question. He repaid this courtesy by pulling a sheaf of yellowed pages from his bosom and unfolding them before her. Cathinka nodded at the papers. “What do you have?” she asked.

“One of Don Ignacio’s logs. In it he details the events that led him, so many years ago, to save your father’s life. The Count, it seems, had been apprehended by a band of savage

indios

while trying to force his affections on one of their maidens. Don Ignacio bartered with the band to spare him. If you wish to adhere to the principles of your worthy sire, Cathinka, your present behavior far exceeds that lenient standard.”

“Go,” said Cathinka imperiously.

Waldemar bowed, but before taking his leave he tossed to the floor of her apartment the pages of Don Ignacio’s log. When he was gone, Cathinka gathered these and read them. Afterwards she wept. By disillusioning her about her father’s past, her lover had also disillusioned her about the nature of his own character. Two birds with one stone. The pithiness of this adage struck Cathinka for the first time, and she passed a restless, melancholy night.

Now, she believed, Waldemar would abandon Cancer Keep. He was not constrained by promises or provisos, and she rued the lovelorn folly of her second wish. The sooner he absented himself from her life the sooner she would be able to marshal her wits toward a purpose in which he had no part.

But Waldemar chose to remain. He ceased picking flowers and writing poems, but he attended her at meals and spoke pleasantly of their youth together in the distant north. Cathinka reflected that she had made mistakes in her life; perhaps she owed her former suitor a mistake or two of his own.

These fluctuations of opinion and mood she continued to record on a daily basis with the electromanuscriber. Sometimes, at night, she could hear Waldemar operating Don Ignacio’s other weird machines—he did not require the monkeys’ aid to make them run. His familiarity with the devices disturbed her. Perhaps those playthings—rather than a concern for her welfare—had induced him to stay. She wrote and wrote, but the matter never became clear.

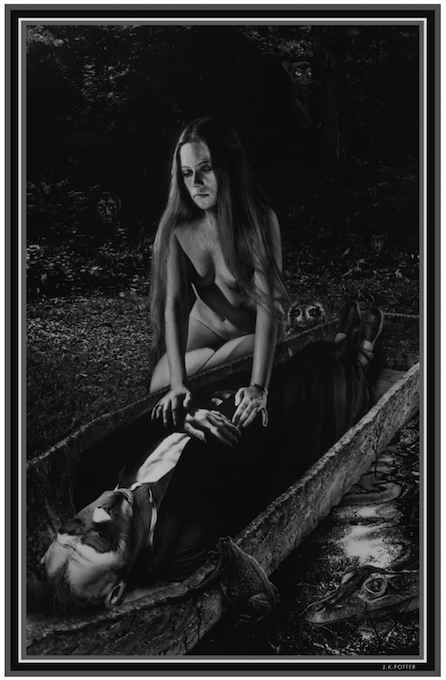

On moonlit nights Cathinka visited the garden and brooded upon her husband’s twisted face and body. An irresistible impulse drew her. He seemed to be wasting away in his slumber. His bones revealed an angular girdering beneath the skimpy fringes of his fur. Like a chunk of bleached stone, his skull appeared to emerge from his eroding lineaments. The moonlight hallowed this process. It was eerie and beautiful. It was plain and repulsive. It was confusing. Cathinka found herself compulsively robing Don Ignacio’s quasi-cadaver in memories of his tenderness and patience. As his body deteriorated and his face screwed up like a pale raisin, the intelligence once animating him lived again in her imagination. She likewise recalled the mystic force in his hands, the grim urgency of his gaze.

For months, however, his hands had been fisted and his eyes closed. What if he died before their third anniversary? She had specified a ten-year slumber, and Don Ignacio had acceded to this adjective without apparent misgivings, but what if her qualifier could not infallibly enforce a ten-year sleep? The premature death of her husband would deprive her of her third wish.

Fool! Cathinka scolded herself. The death of your husband would free you to embrace Waldemar without recourse to wishes.

This realization did not comfort her.

Walking back to her apartment that night, she thought she heard her electromanuscriber clattering disjointedly. Then this sound stopped. Bewildered, she proceeded to her room. Inside she found Waldemar tinkering with the device. Seeing her, the young man pulled a piece of foolscap from the apparatus and tried to crumple it in his hands. Cathinka wrested the sheet from him and read the brief document in an outraged instant. It bore on its face an unfinished story in which she, Cathinka, employed her third wish to bestow great wealth and power on the impoverished prodigal, Waldemar. His parents (this document attested) had disinherited him for his many conspicuous debaucheries, but with the wealth and power accruing from her third wish he intended to revenge himself upon them. Waldemar hastily explained that this narrative was a fiction spun out to test the efficacy of his repairs upon the electromanuscriber—which, when Cathinka put her hands to it, no longer worked at all.

“You wrote that on

my

apparatus in the hope that doing so would influence my third wish,” Cathinka accused him. “But the unseemliness of your desires has caused the machine to break, exposing your villainy. Waldemar, I ask you to depart from here forever.”

“Not until you have made your final wish.”

“Months remain before that is possible, and I hardly intend to heed your recommendations about what my last wish should be.”

Waldemar, his eyes flaring, exclaimed that tonight would serve as well as her anniversary day. If she did not agree, he went on, he would slay the unnatural Don Ignacio in his ready-made coffin and thereby eliminate the possibility of her making any wish at all. To carry out this threat, he rushed from Cathinka’s room and down the open corridor toward the garden. Despite the tropic heat, Cathinka wore a short-sleeved frock with a long embroidered train. She could not hope to catch or struggle successfully with Waldemar in such a garment. Instantly, she shed it. Then, wearing only an ivory-colored chemise and matching pantalettes, her long hair flying, she sprinted off in pursuit of the duplicitous young man.

In the garden she found Waldemar in a posture of resolute strain, his back bent and his fingers curled to prise the canopy from the pirogue. His arms came up, and the transparent cover flipped into the knotted weeds as if it weighed no more than a jellyfish.

In later years Cathinka recalled that instead of daunting her, this sight sent a thrill of imminent combat surging through her, an energy that may have sprung from the heroic suppression of her natural longings. Or perhaps this energy was the force of righteousness asserting itself at the dare of bald-faced iniquity.

As Waldemar reached for Don Ignacio, Cathinka plunged through the snaky vines and luscious equatorial flowers, seized him by his hair, and hurled him aside as easily as he had flung the dugout’s crystal lid. He caught himself against the thorny bole of a tree and charged Cathinka, howling.

They grappled, Waldemar and Cathinka, standing upright and moving so little that an uninformed observer might have thought them spooning. Their individual strengths were isometric. Monkeys gathered on the tiled roofs and thatched breezeways to watch the combat, but the combatants merely swayed in each other’s arms. Puzzled by this behavior, the Moon (upon which people had lately walked) looked down with its mouth open. A bird screamed, and the hush of the jungle became the bated breath of Cathinka’s own briefly recurring uncertainty. Did she love this man or hate him?

She hated him.

Summoning the resources of outrage, Cathinka shoved Waldemar away. As he sought to reinsinuate himself into her arms, there to squeeze her ribs until they cracked, she struck him in the mouth with her elbow. He reeled away, his lip bleeding. She butted him in the shoulder with her head, stepped aside, cuffed his ear with her fist and forearm, received an answering blow to the temple, staggered, delivered an uppercut to his abdomen from her crouch, stood upright, ducked a battalion of knuckles behind which his angry face shone almost as bright as the Moon’s, shot both hands through his routed defenses, levered her thumbs into his Adam’s apple, and tightened the tourniquet of her fingers around his neck. He retaliated by kneeing her between the legs as if she were a man. A host of capuchin spectators scampered from roof to roof, lifting a babel of ambiguous encouragement above the compound, or falling eerily silent whenever one of the combatants seemed on the verge of dispatching the other.

The fight lasted hours. It swung from this side of the garden to that, now in favor of Cathinka, of Waldemar next, and of neither in the gasp-punctuated intervals. Don Ignacio slept through it all as a baby sleeps through family arguments, thunderstorms, air-raid sirens. Cathinka had done no horseback riding or archery exercises since her departure from her father’s estates, but she had substituted walks about the monastery maze and the juggling of small weights to maintain her muscle tone, and she had had more time to adjust to the élan-sapping mugginess of the tropics than had Waldemar—thus, toward morning, the grunting young man had utterly exhausted himself. His masculine pride had offset his imperceptible pudginess for as long as it could. Cathinka, clasping her hands and swinging them into his chin like the prickly head of a mace, put period to their monomachy. Among the needles of a flattened succulent Waldemar lay bruised and torn, still marginally aware but unable to rise. Cathinka stood over him in the tattered white banners of her chemise, greatly resembling the central figure in the Delacroix painting

Liberty Leading the People

.

Disappointed that the fight had concluded, the capuchins took no interest in the stark symbology of Cathinka’s appearance. They returned to the jungle or to the more dilapidated cloisters of Alcázar de Cáncer to rest. It would take them a day or two to recover from what they had witnessed.

Later Cathinka provisioned Waldemar and sent him away in the company of those of Don Ignacio’s cousins who had not slunk off to sleep. She and the young man exchanged no words either during the preparations for his trek or at the final moment of his sullen decampment. Parrots and cockatoos flew aerial reconnaissance missions to insure that Waldemar did not attempt to double back. Cathinka was alone again.

A transcendent peacefulness descended on her spirit. She took off her ruined chemise and stepped out of her pantalettes. She bathed her wounds in well water. She replenished her strength with fruits. She slept naked in her apartment under the gaze of a blue-wattled lizard. That night, and the night after, and so on for every night until the third anniversary of her marriage to Don Ignacio, she visited her husband’s bier in this prelapsarian attire. His scrunched body appeared to straighten, his scrunched features to unwrinkle. He slept on, of course, but a modicum of health was his again and the dreams flickering through his slumber softened his monkeyish face without making it a whit more human. Cathinka did not care. She attended Don Ignacio as often as an experimental animal visits its food tray. Far from dulling the sensibilities of their prisoners, some habits are vital and sustaining. Or so Cathinka slowly came to believe. Now that nakedness was her habitual raiment she felt herself an inalienable part of Cancer Keep.

During the last few days before the third anniversary, a tuft of beautiful white hair began to sprout on Cathinka’s breastbone. It ran by degrees from her throat to her cleavage, spreading over her breasts the way frost furs sun-bleached boulders in a winter stream. This fur gleamed on her opalescent body, and, curling a forefinger in the tuft at her throat, she sat gazing on the magical creature in the pirogue. Finally, on the day that Don Ignacio had told her to make her last wish, Cathinka clasped her husband’s paws and softly spoke it. . . .