Who Made Stevie Crye? (22 page)

Read Who Made Stevie Crye? Online

Authors: Michael Bishop

Tags: #Fiction, #science fiction, #General

“I don’t mother-hen my commas.”

“Glad to hear it. Here’s an example of what I’m talking about. You’ve sent me sample essays and an outline. The outline puts the essay you call ‘The Empty Side of the Bed’ well back in the text, after short pieces about Ted’s illness, his death, and so on.”

“The order’s chronological.”

“So’s history, Stevie. But you don’t have to write it that way. Ever hear of

in medias res

? I want you to make ‘The Empty Side of the Bed’ your leadoff piece. It sets a mood and a tone you discard for a world-weary humor in most of the remaining essays, but it’s the measure of your predicament and the baseline you have to play a lot of your shots from. It belongs at the beginning. That’s the kind of crafty editorial interference I’m talking about.”

“The beginning?” murmured Stevie.

“Listen, I’ll read you some of what you wrote. I’ll show you why I’m a better judge of how good you are and what needs spotlighting than even the author herself.

“ ‘The empty side of the bed is haunted,’ ” David-Dante Maris began in a mellow baritone; “ ‘often I do not turn back the coverlet on that side, but even with the bedspread pulled taut over both linen and pillow, a memory weights the mattress and keeps me hollow company. I know that he has died (I have no illusions on that score, particularly during the day), but when I wake in the middle of the night and turn toward the unrumpled portion of our bed, I feel that at any moment he will settle in beside me again. He is simply off on an insomniac ramble. In a moment he will return. The motionless vacancy beside me and the vagrant one next to my heart will vanish together.

“ ‘The empty side of the bed reminds me that I am an amputee,’ ” Maris continued. “ ‘An accident has occurred, and anonymous benefactors have spirited away the wounded part that their best ministrations could not save. I emerge from anesthesia to find my leg gone. Phantom pains rack the absent limb. The empty side of the bed—here in my house, not in some metaphorical reverie—supports a phantom equally impossible to touch. Knowing that—’ ”

“Stop,” said Stevie.

“What’s the matter?” asked David-Dante Maris.

Stevie did not reply.

“All right. I understand. It goes at the beginning, though. I don’t care if the tone of the piece contradicts the wry exasperation of the other essays. ‘The Empty Side of the Bed’ shows where this wry exasperation comes from and the progress you’ve made swimming out of the shoals of your grief. It goes

first

, Stevie.”

“Maybe I haven’t made any.”

“What?”

“Maybe I haven’t made any. Maybe I write a better game than I play.”

“Bullshit, gal. You play it by writing about it. That’s a perfectly legitimate approach. Briar Patch wants your book. We’ll probably want your second one. You should try your hand at fiction, too. We’re expanding into that area, and I’m committed to developing and publishing important storytellers and novelists right down here in Crackerland. You’re going to be one of them.”

“I don’t write fiction.”

“Okay, but you

could

. If Spiro Agnew and his ilk can write novels, Stevie, anybody can. Why, two weeks ago Rhonda Anne Grinnell turned in a novel. It emits a suspicious fragrance, but we’ll print it because it’ll set B. Dalton’s ablaze and underwrite half a dozen better books.”

“Rhonda Anne Grinnell? A novel?”

“A multigenerational saga spanning three centuries. It’s only 147 pages, but the lady’s daily columns have trained her to work in short bursts, and the novelty of so much compact tawdriness may play to our advantage. Anyway, if Rhonda Anne Grinnell, then why not the bodaciously sensitive Stevenson Crye?”

“The bodaciously sensitive Eleanor Roosevelt never wrote novels. Neither did Martin Luther King. Can’t we just worry about the proposal in hand?”

“Stevie, we’ve just published a book by a new Columbus novelist. He’s more in the Edgar Allan Poe than the William Dean Howells tradition, but he’s an interesting talent. I’ll have Jenny send you a copy of his book by United Parcel Service. You should get it tomorrow.”

“What’s his name?” Stevie asked uneasily.

“The name on the title page is A. H. H. Lipscombe. That’s a pseudonym, and one of the clauses in the contract we signed with the man prohibits us from disclosing his true identity. I call that our B. Traven clause. It’s original with Lipscombe. I let him stick it in because I’m excited by his book.”

“What about

my

contract?”

“I’ll send it to you with Lipscombe’s novel. Take a week with it, longer if you like. Remember you’ve got a sure thing at the Briar Patch—an enthusiastic editor, proven promotional methods, and the promise of a brilliant literary future. We’re not Alfred A. Knopf, but we’ve only been around about six years.”

“I appreciate all this,” Stevie said. “It’s been an education, talking to you. I don’t think I’ve

ever

been on long-distance for such a stretch.”

“I’ll be waiting to hear from you, Stevie.” Maris gave her a number to call, collect. “In the meantime, if you’re having trouble with your work, try your hand at a short story. Take an incident from your own experience—a persistent fear or desire—and build a fantasy around it. Use your typewriter. Let your subconscious run. Give it a goose and watch it go. I’ve a hunch Stevenson Crye’s going to hit the mother lode, the biggest vein of pure gold in Georgia since the Dahlonega hills played out. Or since Margaret Mitchell, anyway.’’

“No, that’s impossible. That’s—”

“Nothing’s impossible. Goodbye, Stevie. Sweet dreams.”)

The receiver’s rude drone reminded Stevie that she had left her bedroom phone off the hook. When she went upstairs to check, though, she found she had no problem. The dialing element snugly cradled the receiver, thank you. ’Crets did this, Stevie thought. Seaton’s monkey is haunting my house. Ted used to haunt it, but now my most unsettling ghost is an evil capuchin from Costa Rica. That creature came in and hung up the phone for me.

“I don’t want your help,” Stevie said aloud.

Maris’s call had deferred her lunch break. She returned to the kitchen and prepared a pimiento-cheese sandwich and a small basket of tortilla chips. She ate without tasting her food. A reputable Atlanta publishing company had just offered to buy her first book. Why, then, had her elation failed to endure beyond the completion of the call? She ought to be celebrating. Instead she was eating a pimento-cheese sandwich and thinking about the manifold phantoms to which emptiness often gives rise.

XL

THE MONKEY’S BRIDE

by

Stevenson Crye

Born of noble parents

in a far northern country where summer lasts an eyeblink and winter goes on like rheumatism, Cathinka was a formidable young woman nearly six feet tall. In mid-July of her eighteenth year, with the snows in grudging retreat, she passed her time roaming the upland meadows in the company of a stocky, fair-haired young man named Waldemar, whose diffident suit she encouraged because his parents were well situated in the village, and also because a startling flare-up of inspiration or temper would sometimes transfigure the dull serenity of his pale eyes. Cathinka still believed that in any important conflict between Waldemar and her, she would prevail. If she did not prevail, it would be by choice, as a secret means of persuading her future husband that she did

not

triumph in every decision or argument.

Fate dismantled Cathinka’s plans in the same indifferent way that a child’s fingers mutilate a milkweed pod.

Arriving home one evening from an outing with Waldemar, Cathinka found her mother and father awaiting her in the drafty library where her father kept his accounts and scribbled away at his memoirs. Once complete, the young woman reflected, these memoirs must assuredly take their place among the dullest documents ever perpetrated by human conceit. What had her father ever done but oversee his vast holdings, engage in stupid lawsuits, and so shamefully coddle Cathinka’s mother that the poor woman now regarded each blast of winter wind as a cruel assault on her personal comfort?

That both the Count and the Countess appeared flustered by her arrival annoyed, as well as surprised, Cathinka. Then she saw that they had a guest.

Wrapped from head to foot in rich white silk, a hood cloaking his features, a cape covering his hands, this personage stood between two of the black-marble pillars supporting her father’s gallery of incunabula. Although several inches shorter than Cathinka, the visitor commanded her awe not only because of his outlandish appearance, but also because of his bearing and odor. He slouched within his elegant garments, and the smell coming from him, although not offensive, suggested an exotic ripeness near to rot. Stammering, Cathinka’s father introduced their visitor as Ignacio de la Selva, her betrothed. She and the newcomer would be married in this hall in a ceremony one week hence.

“I am Waldemar’s, and he is mine!” Cathinka raged, storming back and forth like a Valkyrie. She cowed her father and reduced the shrewish Countess to a stingy sprinkle of tears. Out of the corner of her eye, however, Cathinka could see that Don Ignacio had neither fallen back nor flinched. He was peering out of his concealing hood as if enjoying the spectacle of an elemental maiden defending the romantic Republicanism of her young life. “Never have I heard of this man, Father! Not once have either of you mentioned him, and suddenly, your selection of the moment an irony too bitter to be laughable, you announce that I am to be this stranger’s bride! No!” she concluded, clenching her hands into fists. “No, I think not!”

Don Ignacio strode forward from the alcove and threw back his silken cowl. This gesture elicited a sharp cry from Cathinka’s mother and prompted the abashed Count to turn sadly aside. For a moment Cathinka thought that their visitor was wearing a mask, a head stocking of white wool or velvet. However, it quickly became clear that Ignacio de la Selva bore on his scrunched shoulders the face and features of a monkey, albeit a man-sized monkey. Indeed, his abrupt gesture of unveiling had also disclosed simian hands, wrists, and forearms, along with an ascot of white fur. Her betrothed—God have mercy!—was not a man like Waldemar, but a beast whose diminutive cousins were sometimes seen with gypsies and tawdry traveling circuses.

Cathinka barked a sardonic laugh. Seldom, however, did she disobey her parents, preferring to browbeat them by daughterly degrees to her own point of view. Tonight they would not be browbeaten; they deflected her rage with silence. Recognizing, at last, the hopelessness of converting them, Cathinka fell weeping to the flagstones. To escape marrying the monkey-faced stranger, she might kill herself or flee across a glacial desert—but, without the Count’s blessing, she would not marry Waldemar, either. Even as she wept, then, she began to adjust her sentiments into painful alignment with her parents’.

Perhaps her intended one (whose white whiskers and hideously sunken eyes must surely betray his great age) would not long outlive their wedding day. After all, his face reminded her of those chiseled icons of Death so common to the Lutheran churchyards of her country; and if Don Ignacio died within two or three years, or even if he persisted as many as five, she could take to Waldemar the amplified dowry, and experience, of a young widow. If she could tolerate for a while the unwanted affections of her father’s choice, perhaps she could increase her value and desirability to her own. Even so, Cathinka continued to weep and wring her hands histrionically.

“Come,” said the Count, rebuking his daughter without yet looking at her; “Don Ignacio deserves better. When I was young, a foreigner in a land of jaguars and snakes, I stumbled into circumstances that nearly proved fatal. For trespassing upon an arcane local custom, the chief of an Amazonian Indian tribe wished to deprive me of various parts of my body—but the timely intercession of Ignacio de la Selva spared me these sacrifices, Cathinka, and in gratitude I promised to grant him any boon within my power, either at that moment or at some future moment when my fortunes had improved. ‘Twenty years from now,’ said Don Ignacio, ‘is soon enough.’ Until this noontide I had forgotten my promise, but my friend —” nodding at the monkey-man—“arrived today to remind me of it, and the boon he demanded above all others, darling Cathinka, was my only daughter’s hand in marriage. I have broken a Commandment or two, but never a promise, and you must surrender to this fated arrangement without any further complaints or accusations.”

Said Don Ignacio, stepping forward, “I am a former member of the Cancerian Order of Friars Minor Capuchins, the white-throated branch. I renounced my vows many years ago, when my fellow monks abandoned me to take part in the latest leftist uprising or the most recent rain-forest gold rush (I forget which), and you will live with me, Cathinka, in the deserted jungle monastery that I have made my castle. We will raise our children unencumbered by political or religious dogma, and you will find freedom in the expansive prison of my devotion.”

Gazing up from the floor into her betrothed’s deep-set eyes, the unwilling bride-to-be replied, “But you’re a papist, while I am a devotee of Danton and the Abbé Sièyes.”

“Indeed, lovely one, we hail from different times, not just different worlds. However, I am no longer what you accuse me of being, a papist, and you are only a hypothetical revolutionary. Why, you cannot even bring yourself to rebel against the benign tyranny of your father and mother.”

At these words, the Countess swooned. Cathinka revived her with smelling salts while the Count and Don Ignacio looked on with unequal measures of interest. The matter was settled.

Because of Don Ignacio’s adamant prohibitions against displays of piety or politics, the wedding went forward without benefit of Lutheran clergy or any guests but a few befuddled family retainers. The Countess wept not only to see her daughter taken, but also to sanctify the bitterness with which the ceremony’s want of pomp imbued her. She had expected nobility from every corner of the land to pack the village cathedral. Instead she must listen to her own husband lead the couple in vows that Don Ignacio had composed himself, and she heard in his feeble voice the pitiful piping of a seagull on a forsaken strand.

Don Ignacio’s vows placed great stress on fidelity. Cathinka was certain that the erstwhile Capuchin had written them with her passion for Waldemar firmly in mind.

As for Waldemar himself, earlier that afternoon Cathinka had parted from him without once intimating that she was shortly to be married to another. With difficulty (for Waldemar did not enjoy those games in which lovers rehearse their steadfastness in the face of various hindrances to their love), she had induced the young man to declare that, should she vanish from his life without warning, he would remain a bachelor for at least ten years before losing faith in her intention to return. As she affirmed the last of her vows to Don Ignacio, Cathinka pondered the rigorous pledge she had extracted from her true lover. Perhaps she had been too stringent. Perhaps, in speaking to the elegant but ugly Don Ignacio words she could never mean in her heart, she had committed a mortal sin. . . .

To seal their vows, the wedding couple did not kiss (a departure from tradition for which Cathinka was deeply thankful), but grasped hands and stared into each other’s eyes. This ritual had its own unwelcome points, however, for Don Ignacio’s gaze seemed to propel Cathinka through a maelstrom of memories to some unfathomable part of herself, while his clawlike hands sent through her palms a force like rushing water or channeled wind.

The journey to Cathinka’s new home took many weeks. She and Don Ignacio shared carriages and ship cabins, but never the same bed. The former friar wore his white silk cloak and cowl whenever they ventured into teeming thoroughfares or the hard-bitten company of deck hands, but he was careless of these garments in the privacy of their makeshift quarters, whether a dusty inn room or the cramped cabin of a sailing vessel. Although he had no shame of his befurred and gnarled body, Cathinka would not even let down her hair in his presence; she slept in her clothes, washing and changing only when her husband resignedly absented himself so that she could do so. Their enforced proximity had made Cathinka more critically conscious of the fact that Don Ignacio was a monkey; his distinctive smell had begun to pluck at her nerves as if it were a personality trait akin to sucking his teeth or drumming his claws on a tabletop. She had married an animal!

Let a drunken sailor put a knife in his back, Cathinka profanely prayed. Let him fall overboard during a storm. But God disdained these pleas.

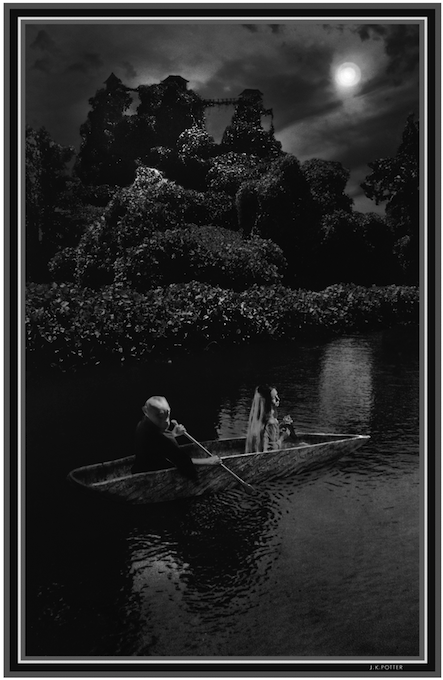

At last, by pirogue through the narrows of a rain-forest river, the newlyweds arrived at the crumbling monastery in the Tropic of Cancer where Don Ignacio had made his home. In pressing his case before Cathinka’s parents he had described this rambling edifice as his castle, but to his horrified bride it more closely resembled a series of rotting stables tied together by thatched breezeways and tangled over with lianas and languid, copper-colored boa constrictors. Satan had gift-wrapped this castle. The heat was unbearable, the fetor of decay ubiquitous, and the garden inside the cloister a small jungle surrounded by a much bigger one. Don Ignacio called the former monastery Alcázar de Cáncer, or Cancer Keep. His retainers were cockatoos and capuchin monkeys, salamanders and snakes, ant bears and armadillos. Cathinka wept.

Over the next several days, she sufficiently composed herself to explore her husband’s holdings. If she must live here, she would try to make, from shriveled grapes, a potable champagne. But what most surprised her was that, in spite of Cancer Keep’s outward disrepair, its dark and humid apartments housed a cunning variety of magic apparatuses, all of which Don Ignacio could awaken by a spoken word or a sorcerous wave of the hand. One machine lifted the contrapuntal melodies of Bach or Telemann into the torpid air; another disclosed the enigmatic behavior of strange human beings by projecting talking pictures of their activities against the otherwise opaque window of a wooden box; yet another contraption permitted Don Ignacio to converse with disembodied spirits that he said were thousands upon thousands of miles away. Cathinka was certain his communicants were demons.

The apparatus that most fascinated the young woman, however, was an unprepossessing machine that enabled Don Ignacio to translate his thoughts into neatly printed words, like those in a bona fide book. Cathinka liked this machine because she did not fear it. Its appearance was comprehensible, its parts had recognizable purposes, and the person sitting before it could direct its activities much in the way that a flautist controls a flute. Don Ignacio called the apparatus an electromanuscriber, and he taught his bride how to use it. She repaid him by continuing to spurn his tender invitations to consummate their union and by employing the machine to chronicle her ever-mounting aversion to both Cancer Keep and the autocratic simian lord who kept her there. She poured her heart out through her fingertips and cached the humidity-proofed pages proclaiming her hatred and homesickness in a teakwood manuscript box.

On errands myriad and mysterious Don Ignacio was often away in the jungle. Although he sometimes offered to take Cathinka, she refused to go. His enterprises were undoubtedly horrid, and she had retained her sanity only by committing to paper through the agency of the electromanuscriber each of her darkest fears and desires. She could not safely interrupt this activity. Occasionally in her husband’s absence, she would stop under a tree riotous with his retainers—birds of emerald plumage and ruby eye, monkeys in brown-velvet livery—to harangue them about their suzerain’s despotism and possible ways of ending it. The cockatoos clucked at her, the capuchins only yawned. Oddly, she was grateful for their want of ardor. She did not really wish Don Ignacio to be borne off violently.