Who Made Stevie Crye? (6 page)

Read Who Made Stevie Crye? Online

Authors: Michael Bishop

Tags: #Fiction, #science fiction, #General

XII

She knew what had happened

. She was not insane. She had heard the Exceleriter typing and had actually found the unfinished product of its labor. If her machine had been functioning as the printer in a word-processing system, she could have attributed its performance to prior programming—but her typewriter was a desk model, with no expensive hookups or modifications, and it should not have been doing what she had seen it do. Telling Dr. Elsa, dumping her impossible discovery into the minor maelstrom of her friend’s workday, had not shown good judgment. Although their friendship spanned a dozen years, Stevie could hardly expect Dr. Elsa to embrace a report as unlikely as the one she had ill-advisedly sought to foist upon her.

All you did, Stevie chided herself, was make her worry. She thinks the pressure has finally worn you down. She thinks you typed that page during an episode of fugue and don’t remember doing it.

Or else she thinks you’re crazy, kiddo.

Stevie wondered if her insanity lay in failing to . . . well, to fear the machine. An electric typewriter that began to churn out highly detailed versions of your dreams warranted a certain awe. It could remake your life. It could reveal your most shameful secrets. It could destroy you. Cataloguing these melodramatic possibilities, Stevie smiled at herself.

In point of amusing fact, a typewriter—no matter how voluble, vulgar, and malicious—had no forum unless you gave it one. It could not saunter from room to room rummaging through your belongings, go to the police chief to denounce your private appreciation of smutty books, or even creep over an inch to upset the bottle of Liquid Paper next to your latest manuscript. A typewriter sat where you put it. If you kept your study door closed and forbade anyone else to enter, it served as your absolute captive.

Stevie intended to make use of these facts. Why, then, should she fear her typewriter? Although hard to lift, it was not otherwise physically imposing. Its grimy platen knobs and mild keyboard grin conveyed not a flinch of menace. Besides, before visiting Dr. Elsa, Stevie had defanged the machine by the simple expedient of unplugging it. If it wanted to get rid of her or ruin her reputation, it would have to wait until she restored its power. When she did, she fiercely believed that Stevenson Crye rather than the PDE Exceleriter would occupy the driver’s seat. She would turn the machine’s occasional self-sufficiency to her own advantage.

That was why she had asked Dr. Elsa for those long sheets of slippery white examination-table paper. Since returning from Wickrath, she had not set foot in her study. She had spent the morning scissoring Dr. Elsa’s “sausage wrap” into streamers about eight inches wide—so they’d fit into the Exceleriter. These virgin scrolls lay about the kitchen—on the breakfast bar, the circular oaken table, the seats of her wobbly captain’s chairs—as if she were trying to convert the place into a medieval library. All her manuscripts lacked were words and meticulous illuminations. The words, at least, would come later.

Teddy came in, dragging his expensive winter jacket and eyeing the paper-filled kitchen.

“You’re home early,” Stevie said, baffled. The clock on the stove showed only a few minutes after noon.

“It’s a teachers’ in-service weekend, Mom. We only went half a day.”

“Oh.” She had forgotten.

“The elementary school let out early, too. Isn’t Marella home yet?”

The day’s plans—some of them formulated at breakfast while she was still trying to absorb the implications of her strange discovery—began to take focus again. “Tiffany McGuire’s mother picked her up, Teddy. Marella’s supposed to spend the night there.”

“She well enough to go?”

“Claimed she was this morning. If she can go to school, I guess she can go to a friend’s house, don’t you?”

“ ’Sno skin off my nose.” Before she could tweak Teddy for the slovenly offhandedness of this remark, he added, “I thought you’d be upstairs working, trying to make up for yesterday and all.”

“Afraid you’ll starve?”

“No, ma’am.” He looked taken aback, and Stevie regretted snapping at him—the guilt of the neglectful breadwinner triumphing over maternal solicitude.

More tenderly, she said, “In a way, I

am

working.”

“Somebody ask you to do decorations?”

“I’m going to type on this, Teddy. I’m halving the strips so they’ll roll into my machine.”

“I thought you typed on typing paper.”

“These are for drafts. From now on I’ll be using long strips like these for almost all my preliminary drafts.”

“What for?” Teddy picked up a tightly wound scroll and thumped it against his chin.

“It’s a psychological thing,” Stevie told him. “When I get to the bottom of a page, I want to stop. If I’ve got a sheet of paper four feet long, though, it’ll take a while to get to the bottom and I won’t be tempted to stop working so often.”

“Mmm,” said Teddy.

“Maybe I’ll increase my productivity.”

Teddy grinned. “And if you don’t, at least you won’t have to buy us a flyswatter this summer.’’ He bopped an imaginary fly on the breakfast bar, tossed the dented scroll into his mother’s lap, and said he was going to Pete Wightman’s house for a patio scrimmage. He had eaten lunch at school. She didn’t need to worry about him.

After Teddy left, Stevie glanced about the kitchen at her handiwork. The real reason she wanted long strips of paper, of course, was so that the automatic activity of the Exceleriter did not henceforth automatically cease at the bottom of a standard eleven-inch sheet, stranding her in the middle of a crucial, maybe even a revelatory, text. The machine was her captive, her slave, and she would put it to work in the service of her own vital goals. No one she had ever known had ever owned a Ouija board of such awesome potential, and if it could help her plumb her own dreams or establish a spiritual contact with her dead husband, then it

must

be put to that use.

She would never mention the Exceleriter’s capabilities to Dr. Elsa again. She would never tell Teddy or Marella. She would never tell anyone. She knew what had happened, and she was not insane.

XIII

That afternoon, Stevie worked with the Exceleriter

as if the complications of the past four days had never arisen. Human being and machine met across the interface of their unique quiddities (Stevie

liked

the metaphysical thrust of that Latinism), and copy poured forth on Dr. Elsa’s butcher paper at a rate of almost six hundred words every thirty minutes. Anthony Trollope had written a good deal faster, of course, but this speed wasn’t too shabby for a gal who had recently been suffering a nasty block. Stevie took a tranquil pleasure in her recovered—even augmented—fluency.

By three o’clock, she was within a paragraph or two of completing her submission proposal for

Two-Faced Woman: Reflections of a Female Paterfamilias

. A shrill buzzing ensued. Stevie’s hands jumped away from the keyboard, but the noise had its origins not in another broken typewriter cable but at the doorbell button downstairs. Thank God. She never liked being interrupted at work, but the doorbell was better than a repetition of Tuesday’s debacle. A jingly SOS, the doorbell rang three more times, and Stevie shouted over it that she was coming, hold on a sec.

At the front door she came face to face with Tiffany McGuire’s mother, who, gripping Marella supportively at the shoulders, favored Stevie with an apologetic smile. “I’m afraid she’s not feeling too good, Mrs. Crye. The other girls wanted her to stay, you know, but I’d hate it if she brought everyone down sick. I’ve got Carol and Donna Bradley, too.”

“Of course.” Stevie could see Mrs. McGuire’s Pinto station wagon under the Japanese tulip tree at the foot of the walkway, a bevy of third-grade girls sproinging about in the backseat. “Thanks for carrying her home.”

But when Marella came into her arms, her heart sank. The child showed a face so drawn and translucent that Stevie could see the blue veins in her cheeks and eyelids, the mortal jut of bone beneath her brow. February was a bad month, of course, but during this past year Marella had frequently come down sick. (Of late she had tried, valiantly, to disguise or mitigate the degree of her discomfort.) It was probably nothing but a nervous stomach. Tuesday, she had contracted a touch of the flu, but today the excitement of spending the night with Tiff—or maybe the small trauma of an argument with Donna Bradley, with whom she had trouble getting along—had caused her upset. A nervous stomach was a funny ailment. Almost any emotional disturbance could trigger it. Stevie wondered, in fact, if Marella had registered her mood that morning at breakfast; the child’s present illness might be a delayed reaction to the disbelief and helplessness that Stevie no longer felt, a kind of sympathetic aftertremor.

“Oh, you poor kid. Come on in.”

Mrs. McGuire having retreated out of hearing, Marella said, “I didn’t want to come home. I could have stayed.

She

got scared, though.” Her frail voice encoded the hint of a forbidden

nyah-nyah

taunt. “

She

was afraid I’d throw up on her carpets.”

“That’s a legitimate fear, daughter mine. I don’t blame her.”

Marella began to cry. “I’ve done it again, haven’t I, Mama?”

“It’s all right. Hush.”

Stevie folded down the sofa bed in the den, settled Marella in with her faithful upchuck bucket and some maze books, and went back upstairs to finish her proposal. Surprisingly, her nagging awareness of Marella’s nervous upset notwithstanding, she resumed work with some of her former enthusiasm and in only twenty minutes had completed the job. Look out, Briar Patch Press, Inc. She used a pair of scissors to separate her draft from the long strip of paper in the machine, rolled out the abbreviated piece, inserted another uncut one to receive whatever the Exceleriter might compose in the hours after midnight, and puffed some air at her bangs. She did not unplug the machine.

The remainder of the evening she spent caring for Marella, cleaning up the dinner dishes, and thumbing through a battered paperback from Ted’s little library of science-fiction novels, something called

The Grasshopper Lies Heavy

. Long before tucking the kids in, she began to anticipate, to build expectation upon expectation. By the time she climbed into bed, Teddy and Marella long since asleep, she understood how hard it would be to join them in slumber. Was the Exceleriter really plugged in? Did it have enough paper? Would she hear it when it began? What would it tell her?

In her flannel nightgown, she tramped to her study to check the setup a final time. She resisted the temptation to turn on the Exceleriter’s electricity; last night it had done that by itself, and if it meant to perform again, it would surely emulate the pattern it had already established. If not, not. Beyond setting the stage, she could not prescribe or direct its untypewriterly behavior.

Still, her parting instruction to the machine was, “Tell me about Ted. Let him finish his confession. I need to know.”

XIV

Awake or asleep?

Awake, surely, for in the next room the resourceful Stevenson Crye, mistress of her fate, tamer of typewriters, could hear the businesslike rattle of the Exceleriter’s typing element, a concert muted a bit by the intervening plaster walls. She sat up in bed. By canny prior arrangement, her robe lay within reach, and she quickly put it on. Her powder-blue mules she found beside the bed exactly where she had left them, and after slipping into these hideous knockabouts she lurched over her carpet into the hall, not pausing to turn on a light.

Her clumsiness Stevie blamed on her excitement, her failure to illuminate either bedroom or hall as an attempt at stealth. In truth, she was afraid to catch the Exceleriter unhandedly clattering away, and her emphatic “Oh, shit!” as she stumbled into her study door sabotaged any last hope of surprising the percipient machine.

It stopped typing.

Stevie hesitated a moment. Maybe it would start again. She wanted to catch the typewriter in the act.

In flagrante delicto

, lawyers called it. Or maybe she wanted no such thing. A kind of prurient ambivalence plagued her—much as a curious child may be of two minds about trying to witness, even from a secure hiding place, its transmogrified parents engaged in an instance of strenuous lovemaking. But the Exceleriter did not resume its unassisted labors, and before Stevie could steel herself to enter her study, she heard a high pathetic moaning from Marella’s room.

“Hot, Mama. Oh, Mama, I’m so hot. . . .”

The house was bitterly cold. Even though she had been out of bed only a minute or two, Stevie’s feet had gone numb. How could Marella possibly be hot? Only if she had a fever. Only if this afternoon’s nervous stomach had given way to an ailment traceable to virulent microorganisms. The poor kid. How much did she have to suffer? How long would these weird and exhausting attacks disrupt their lives? Stevie slumped against the doorjamb. A typewriter that worked by itself, and an intelligent eight-year-old daughter who could barely function twelve straight hours without catching a flu bug or an ineradicable angst. That Teddy continued to sleep astonished Stevie and imperceptibly mollified her despair: the only bright spot in this ridiculous pageant of after-hours calamity.

“I’m melting,” Marella said more clearly. “Mama, I’m so hot I feel like I’m melting.”

Stevie walked down the narrow hall to lean into her daughter’s double-dormer room, their largest bedchamber upstairs. “Are you awake?” she asked in a whisper. “Or are you talking in your sleep?”

“Awake,” the girl said weakly. “Awake and hot. Oh, Mama—”

“I’m coming. Don’t fret. Mama’s here.” Stevie picked her way over the clothes and stuffed animals littering the floor, squeezed between the twin beds at the northern end of the room, sat down on the vacant bed, switched on Marella’s night-light (a porcelain Southern belle in a pleated peach-colored gown), and crooned, “Don’t fret. Mama’s here.” The child shut her eyes against the night-light’s glow and turned her head on the pillow.

Despite her complaints, Marella had not kicked off her covers. She made no move to squirm out from under her electric blanket, which came all the way up to her chin. Stevie laid three fingers across her forehead. It felt lukewarm rather than fiery. The girl’s cheeks were soft pink rather than red, her earlobes as pale as the night-light lady’s tiny corsage of porcelain gardenias.

“Daughter mine, I don’t think you’ve got a fever. You look pretty good. You don’t feel hot.”

“Hot,” she insisted, her eyes still closed. “Melting.”

“Then uncover for a minute. I’ve got the sh-sh-shakes, and you’ll g-g-get ’em too.” Trying to jolly the girl out of her obsession, Stevie held her hands out to demonstrate their shakiness. “Brrrrrrr,” she whinnied.

“All I can move is my head, Mama.”

“That’s silly,” Stevie replied, panic descending. “Why do you say that? What’s wrong?”

“I’m trapped. The blanket’s holding me down and melting me, Mama.” Marella revolved her head back toward Stevie and opened her wild luminous eyes. “It’s my fault, it’s all my fault—I’m not any good.”

“Of course you’re good. Never say that. You and Teddy are the two best things ever to happen to me.” Stevie let her hand drop from the girl’s gossamer-fine hair to the pressure points in her throat. “You’re not paralyzed, Marella,” she said, gingerly touching. “You’re still half-asleep. Push your cover back, you’ll see how chilly it is out here in the cold, cruel world, and everything’ll be okay again. I wouldn’t let anything happen to you. I couldn’t. You’re precious to me, daughter mine.”

“So hot, Mama,” the girl said. “So hot I may’ve already melted.”

“Try to move. Try to push your cover back.”

“I can’t.”

“Try to move!” Stevie insisted. “You’ve convinced yourself a bad thing’s happened, and it hasn’t, Marella. It hasn’t!”

But what if some rare form of paralysis

had

gripped the girl? Stevie’s inchoate alarm began to solidify into a tumorous knot in the pit of her stomach. None of this was fair. If Marella could uncover herself—if only she would make the small symbolic effort involved in shoving her electric blanket aside—why, her delusive spell would be broken, and they could both go back to sleep. As for the Exceleriter . . .

“Mama,” Marella said. “Mama, I’m

trying

.”

“But you’re just lying there. Surely you can

kick

these old covers off.” She made an abrupt flicking motion with her fingers, her smile as tight as a triple-looped rubber band.

Marella began to cry. “Already melted. My fault. So, so hot, Mama. I’m just not any good.”

“Stop saying that, little sister!”

“Call Dr. Elsa, Mama. Ask Dr. Elsa why I can’t move.”

“Marella, we can’t go running to Dr. Elsa with every little problem, especially in the middle of the night. She’s seen too much of me already.”

“Mama, please—you take the covers off me.”

Stevie rocked away from her daughter, clutching her face in her hands. She—the so-called adult—was behaving irrationally. Marella might be seriously ill, paralyzed, and here she was refusing to telephone their family doctor, her own closest friend, just because she had made a fool of herself yesterday morning in that forbearing woman’s Wickrath offices. In this situation, Dr. Elsa would be angry only if she

failed

to call. This was clearly an imperative situation. Stevie stood up.

“Marella, I’m going to call the Kensingtons.”

Tears in the corners of her eyes, the child gave a feeble nod. “You uncover me, okay? Before you call. Just for a minute, Mama. I’m still hot. I’ve already melted, but I’m still hot.”

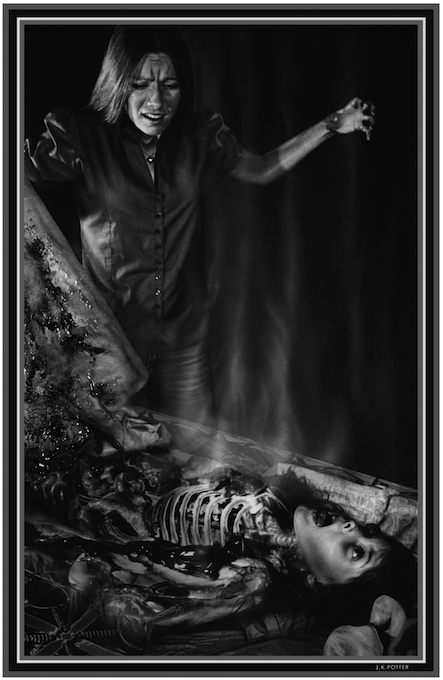

This refrain enraged Stevie. She grabbed the satin hem of the GE blanket and yanked both it and the sheet beneath it all the way to the foot of the narrow brass bed. Then she began to scream.

Her daughter’s lower body, from the neck down, consisted of the slimy ruins of her skeletal structure. Her flesh and internal organs had liquefied, seeping through the permeable membrane of her bottom sheet and into the box springs beneath the half-dissolved mattress, stranding her pitiful rib cage, pelvis, and limb bones on the quivering surface—like fossils washed out of an ancient geological formation. Steam rose into the February air from this odorless mess, and Stevie added her breath to it by screaming and screaming again.

Marella was heedless of her mother’s incapacitating hysteria. “Still hot,” she said. “Oh, Mama, I’m still hot. . . .”