Why Growth Matters (6 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Similarly, following the recommendations of the report “Health for All: An Alternative Strategy,” jointly sponsored by the Indian Council of Medical Research and Indian Council of Social Science Research, the 1983 National Health Policy adopted the provision of universal, comprehensive primary health services as its goal. But it quickly became clear that financial resources for it were lacking.

8

The subsequent National Health Policy 2002 and the National Rural Health Mission 2005 stayed away from the goal of providing universal health care. The issue has forcefully returned recently. Right-to-health legislation is being actively discussed but financial resources, even with more revenues now available, remain a significant hurdle.

9

necessary

for poverty alleviation; redistribution can do the job

.

This proposition may have some salience in industrial countries, which have had the benefit of growth for more than a century. In principle, the high levels of income made possible by prior growth may generate enough revenues to sustain large-scale antipoverty programs even during long-term stagnation. In practice, the situation is not so simple. As we have witnessed during the recent crisis and the associated Great Recession, the need to reduce the huge debt overhang has created a crying need for growth even in the developed countries so as to avoid having to cut spending on social programs.

The situation is many times worse in poor countries, such as India, which at independence already had an overwhelming proportion of its population in abject poverty. Other developing countries, such as Brazil, China, Indonesia, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Thailand, mirror India in this respect. The option to eradicate (rather than making only a minuscule impact on) poverty through redistribution, even if politically feasible, was not available.

There were too few from whom the government could take and too many to whom it needed to give. Furthermore, the government needed to attack poverty on a sustained basis rather than approach it as a one-shot affair. With the country's rising population and stagnant growth, any favorable effects of redistribution on poverty would have quickly eroded.

When the founding fathers opted for a growth-centered strategy, they did so in full knowledge that India's poverty problem was too immense to be solved by redistribution aloneâhence Jawaharlal Nehru's insistence that “to remove this lack and ensure an irreducible minimum standard for everybody the national income had to be greatly increased” (Nehru 1946, p. 438).

Whether poverty could be overcome without growth figured in the First Five-Year Plan and then again in the Second Five-Year Plan, with the planners opting in each case to endorse the critical role of growth in

the assault on poverty.

10

In the early 1960s, when poverty and income distribution became the subject of heated debates in the parliament and Prime Minister Nehru became concerned with the question of where the growing incomes were going, the Perspective Planning Division of the Planning Commission took another careful look at the policy options. Among other things, the fifteen-year plan it produced offered a coherent and clearheaded analysis of why growth was necessary.

The plan (Pant 1962) began by noting that the income and consumption distribution data showed that approximately 50 percent of the population lived in abject poverty on 20 rupees or less per month at 1960â1961 prices. It then proceeded to argue the need for growth:

The minimum which can be guaranteed is limited by the size of the total product and the extent of redistribution which is feasible. If at the current level of output, incomes could be redistributed equally among all the people, the condition of the poorest segments would no doubt improve materially but the average standard would still be pitifully low. Redistribution on this scale, however, is operationally meaningless unless revolutionary changes in property rights and scale and structure of wages and compensations are contemplated. Moreover, when even the top 30% of the households have an average per capita expenditure of only Rs. 62 per month, it is inconceivable that any large redistribution of income from the higher income groups to the other can be effected. To raise the standard of living of the vast masses of the people, output therefore would have to be increased very considerably. (pp. 13â14)

Moreover, Pitambar Pant's document had a novel argument about the need to grow the pie rather than share it more generously. Based on Bhagwati's work in Pant's division, the document went on to examine the income distribution data available at the time for several countries and argued that the distribution of incomes in countries at very different levels of income followed a remarkably similar pattern.

11

In particular, the proportion of incomes earned by the lowest 30 or 40 percent of the population appeared stable across countries. Therefore, it followed that

a strategy of redistribution, or changed political orientation, did not offer a panacea and that “growing the pie” seemed to be the only effective way to bring the groups at the bottom of the distribution up to “minimum” standards of living.

Since there were groups such as tribes that were outside the mainstream economy, the document recommended a strategy of poverty reduction that relied on growth for the population that was or potentially could be integrated into the economic mainstream, and on redistribution for those outside the mainstream. Using a formal model, it calculated that in fifteen years a 7 percent growth combined with redistribution to those outside the mainstream could potentially eliminate abject poverty measured by 20 rupees per capita income at 1960â1961 prices.

On the other hand, the argument that poverty could be overcome without growth acquired some salience among Indian intellectuals following its advocacy by Mahbub ul Haq, a Pakistani economist. In his 1972 article “Let Us Stand Economic Theory on Its Head: Joining the GNP Rat Race Won't Wipe Out Poverty,” Haq argued that whereas China, with only modest rates of growth, had eradicated through redistribution the worst forms of poverty, illiteracy, and malnutrition with only modest rates of growth, other countries including India, which had focused on growth, had missed the boat.

12

We now know that the premise on which Haq based his argument was false. On the one hand, China had struggled to achieve speedy growth by extracting surplus from agriculture for investment in urban industry and in the process allowed millions of people to lose their lives. On the other hand, China was quite far from eradicating the worst forms of poverty, illiteracy, and malnutrition as late as 1971.

13

In India itself, despite the justified skepticism about redistribution as the solution to sustainably assault poverty, modest redistribution did take place through expenditures on health and education. For instance, as the fifteen-year plan by Pitambar Pant noted, the 40 percent increase in income between 1950â1951 and 1960â1961 had allowed improvements in the social sphere, such as an 85 percent increase in school enrollment and a 65 percent increase in the number of hospital beds. But this was hardly a drop in the ocean of poverty.

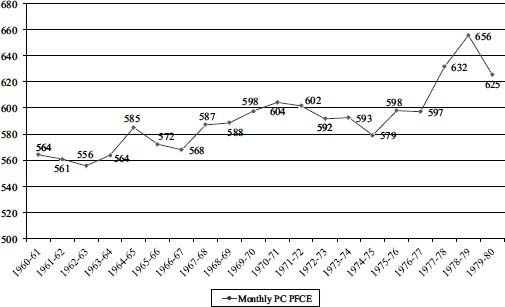

Figure 2.1: Monthly per capita private consumption expenditure, 1960â1980

The situation did not much improve until almost the late 1970s. This is demonstrated by

Figure 2.1

, which shows countrywide per capita private final consumption expenditure per month from 1960â1961 to 1979â1980 at 1999â2000 prices.

14

We can see that the private final consumption expenditure rose from 564 rupees per capita per month in 1960â1961 to just 597 rupees in 1976â1977âa mere 2 percent increase in sixteen years! The scope for redistribution had scarcely risen beyond what was feasible in 1960â1961.

sufficient

to reduce poverty; redistribution is necessary.

15

Remember that the Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq was the most prominent writer in the early 1970s to condemn the growth-centered strategy and to celebrate the alternative policy of redistribution instead.

16

With India turning to socialism under Indira Gandhi, Haq found a constituency of left-wing journalists, academics, and policy makers in the country eager to embrace him. A cottage industry under

the self-congratulatory rubric of “New Economics,” whose basic premise was that growth by itself was not going to lead to any reduction in poverty, soon grew.

17

Even Prime Minister Indira Gandhi seemed to give the premise a nod when she stated in her famous March 25, 1972, speech to the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, “Growthmanship which results in undivided attention to the maximization of GNP can be dangerous, for the results are almost always social and political unrest. Therefore, increase in the GNP must be considered only as one component of a multi-dimensional transformation of society.”

18

That this multiplicity of instruments (and a broad range of social objectives around the main theme of poverty reduction) was indeed what the Indian planners had long embraced was lost in a flourish of false assertions by her speechwriter of the novelty of her claims and the erroneous condemnation of what was the true situation earlier.

True enough, as we have stressed, state-financed programs to aid the poor can (when efficiently planned and run) help speed up poverty reduction in a growing economy that progressively enlarges the scope for such spending through increased revenues. Thus, remember that growth helps by drawing the poor into gainful employment, and it

additionally

helps by generating revenues that can be used to aid the poor through programs targeted at the health and education of the poor.

19

But we cannot emphasize enough that the view expressed by Indira Gandhiâthat even without this revenue effect, if India had only growth by itself, it would have done nothing for the poor (and would in fact have been “dangerous”)âfinds little support in either conceptual analysis or empirical reality.

Conceptually, in an economy with widespread poverty, labor is cheap. Therefore, it has a comparative advantage in producing labor-intensive goods. Under pro-growth policies that include openness to trade (usually in tandem with other pro-growth policies), a growing economy will specialize in producing and exporting these goods and should create employment opportunities and (as growing demand for labor begins to cut into “surplus” or “underemployed” labor) higher wages for the masses, with a concomitant decline in poverty.

Countries such as South Korea and Taiwan offer ample empirical evidence precisely in support of this argument. These countries managed to put in place the right mix of policies from the second half of the 1950s onward and were able to achieve high rates of growth. In turn, they were able to pull workers from agriculture in the hinterland into labor-intensive manufacturing in ever-larger volumes, resulting in steadily rising wages. The end result was a massive reduction of poverty. Rapid growth had “pulled up” the poor into productive employment and out of poverty.

20

We will discuss in later chapters that growth has had a direct impact on poverty in India as well. However, continuing regulations that have prevented this process from fully working have handicapped the linkage. In particular, as we document in

Part II

, until at least 2000, the small-scale industries reservation, which required virtually all labor-intensive products to be produced exclusively in very small enterprises, kept India uncompetitive in these products in the world markets. But even though this regulation was considerably weakened by 2000, labor-intensive goods, such as apparel, footwear, and light manufactures, failed to show rapid growth on account of continuing labor-market inflexibilities.

The protection to labor in larger firms is extremely high in India and translates into excessively high effective labor costs. As an example, Chapter VB of the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947 makes it nearly impossible for manufacturing firms with one hundred or more workers to lay them off under any circumstances. Such high protection makes large firms in labor-intensive sectors in which labor accounts for 80 percent or more of the costs uncompetitive in the world markets. Small firms, on the other hand, are unable to export in large volumes.

Because of this limitation, growth in India has been driven instead by the capital- and skilled laborâintensive sectors, such as automobiles, two- and three-wheelers, engineering goods, petroleum refining, and the software and telecommunications industries. Despite this limitation, growth has helped alleviate poverty through an indirect mechanism.

21

Rising incomes in the fast-growing sectors have led to expenditures that led to gainful employment in the non-trade-services sectors. Thus, for example, the proliferation of automobiles generates the demand for driv

ers and mechanics. As cell phones proliferate, retail outlets for their sales must expand. Rising demand for housing gives rise to employment opportunities in construction. Generally rising expenditures also increase the demand for passenger travel; telecommunications, fax, and courier services; tourism; restaurant food; beauty parlors; education; medical, nursing, and veterinary services; and garbage collection. Employment in these non-trade services thus offers an alternative avenue to poverty reduction as growth accelerates.