Why Growth Matters (7 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Evidence linking poverty reduction to growth can also be gleaned by comparing per capita incomes and poverty rates across states in India. There is a strong negative correlation between per capita incomes of states and the poverty ratios.

22

Making the plausible assumption that redistribution policies across states do not vary much or that they are biased in favor of states with larger concentrations of poverty, this correlation would imply a positive relationship between per capita income and poverty reduction.

23

Indeed, the evidence that the old policy framework had undermined growth and that growth would reduce poverty and be inclusive was so strong that only die-hard proponents of the old policy framework, many on the Left who professed to be pro-poor, were in the skeptical, or hostile, camp in the battle for reforms. Since nearly everyone had started on the same bus that they had boarded when being educated in England, perhaps the apt analogy was that, while many such as Bhagwati and Manmohan Singh had gotten off that bus as they observed the devastation around them, these opponents were still on the bus. They fancied themselves as Rosa Parks; in truth they were just intellectually lazy and unwilling to learn from the ruin they had visited on India and its poor. So, when the reforms started in earnest, they would oppose them, developing a new set of myths about the downside of the new reforms and the upside of the old policy framework that was being discarded.

Reforms and Their Impact on Growth and Poverty

The economy is in crisis. . . . We are determined to address the problems of the economy in a decisive manner. . . . This government is committed to removing the cobwebs that come in the way of rapid industrialization. We will work towards making India internationally competitive, taking full advantage of modern science and technology and opportunities offered by the evolving global economy. . . .

We also welcome foreign direct investment so as to accelerate the tempo of development, upgrade our technologies and to promote our exports. Obstacles that come in the way of allocating foreign investment on a sizable scale will be removed. A time-bound program will be worked out to streamline our industrial policies and program to achieve the goal of a vibrant economy that rewards creativity, enterprise and innovativeness. . . .

Our vision is to create employment, eradicate poverty and reduce inequality. We want social harmony and communal amity. We want a more humane society. As the twentieth century draws to a close, we cannot live with poverty and destitution among large sections of our population. [Mahatma] Gandhi said that it was his ambition to wipe every tear from every eye. That is the vision which will inspire the work of my government.

Jai Hind

.

âPrime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao in an address to the nation upon taking the office, June 22, 1991

B

y

the second half of the 1970s, the sorry plight of the economy, accentuated dramatically with the turn to socialist policies under Indira Gandhi, had become evident to those who did not wear ideological blinkers.

But the grip of socialist rhetoric on the national psyche was so overpowering that few dared to challenge the policy framework itself. Therefore, the response was a very gradual, almost imperceptible process of unwinding the controls without disturbing the underlying framework.

1

This process accelerated somewhat under Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, who took the reins of the government at the end of 1984 following the assassination of his mother, Indira Gandhi.

Through the 1980s, doubts concerning the controlled regime grew steadily even if only gradually. But as the decade ended, the doubts were greatly heightened and confidence in the model India had followed was at a low point. It was further shaken by two external events: the success China had achieved after it turned outwardâthis was “learning by others' doing”âand the demise of the Soviet Unionâwhich was “learning by others' undoing”âthat had served as the model for Indian planners from the 1950s until at least the end of the 1970s. Therefore, when a balance-of-payments crisis in 1991 offered the opportunity to make more dramatic changes, newly elected Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao, who came to the helm due to the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi during the election campaign and who had experienced the tyranny of central controls as the chief minister of Andhra Pradesh in the early 1970s, did not hesitate.

2

He launched a process of systemic reforms that firmly put India on a dramatically different course from the one Indira Gandhi had set for the nation.

These reforms posed the greatest challenge to the long-standing proponents of socialism, who now faced an existential threat. Unsurprisingly, their response was to take an offensive strategy designed specifically to undermine the credibility of the reforms. This required the creation of several new defensive myths. In this chapter, we address these myths, which relate to the alleged malign impact of the reforms on growth, poverty, and socially disadvantaged groups. Additional

myths relating to the presumed deleterious impact of the reforms on inequality, education, health, and related issues are discussed in

Part II

.

.

The most surprising myth, surviving among a few economists, is that although growth did occur after reforms, it was not a result of the post-1991 reforms and that instead it can be traced back to the 1980s.

We have seen that the command-and-control regime had peaked by the mid-1970s and a quiet process of loosening some of the controls began soon after, accelerating somewhat in the 1980s, especially under Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. It was this halting, partial process of reforms, introduced as it were “by stealth,” that was replaced in 1991 by the reforms package that brought the liberalizing process into the open, made reforms more comprehensive across important issue areas, such as industrial licensing, and represented a fundamental shift in the policy framework.

3

So, we must ask: How can serious economists maintain that the reforms had no effect on the post-1991 acceleration of growth? Their argument takes one of two forms. They claim that first, the growth acceleration really started in the 1980s, and second, even that was a result not of the piecemeal reforms of the 1980s, but of “attitudinal changes,” which trumped the effects of any specific, concrete reform measures.

The economic historian Bradford DeLong (2003) was the first to argue that the post-1991 reforms followed rather than preceded the growth acceleration. But his claim that growth acceleration started in the 1980s did not automatically imply that reforms as such had nothing to do with the shift in the growth rate. Indeed, DeLong acknowledged that the reforms in the 1980s may have led to the acceleration in growth in that decade, and so one could not conclude that reforms and growth were not related. Going a step further, he also speculated that the 1980s growth acceleration might have proven to be just “a short-lived flash in the pan” in the absence of more comprehensive reforms of the post-1991 variety (as is indeed true).

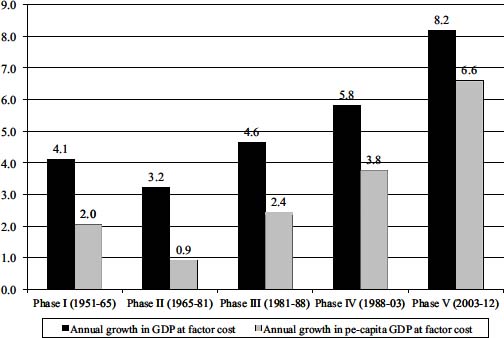

Figure 3.1. Annual growth rates of the GDP and per capita GDP during various phases, 1951â1952 to 2011â2012

Source: Authors' construction based on data from the

Handbook of Statistics on India's Economy

, 2012, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai

The real problem lay with the separate assertion by Dani Rodrik (2003), in his editorial introduction to the volume carrying DeLong's paper, that the 1980s growth had little to do with reforms in any case. He argued that “the

change in official attitudes

in the 1980s, towards encouraging rather than discouraging entrepreneurial activities and integration into the world economy, and a belief that the rules of the economic game had changed for good, may have had a bigger impact on growth than any specific policy reforms” (emphasis added).

4

However, both DeLong's statistical assertion about allegedly robust pre-1991 growth and Rodrik's explanation for it are wrong.

5

First, the claim that growth in the 1990s was no higher than in the 1980s carries what might be called a fallacy of aggregation. The acceleration in the early 1980s was in fact quite modest (see

Figure 3.1

), with the bulk of the growth back-loaded in the last three years of the decade. Once we exclude the years 1988â1991, growth in the remaining yearsâ1980â1981 to 1987â1988âturns out to be just 4.6 per

cent, which is closer to the 4.1 percent growth that had already been achieved between 1951â1952 and 1964â1965 and perceptibly lower than the 5.8 percent during 1988â2003 or 6.3 percent between 1992â1993 and 1999â2000.

6

Chetan Ghate and Stephen Wright (2008) have recently applied state-of-the-art techniques to detailed state- and industry-level data to identify the turning point of the economy. The authors' careful and comprehensive work places this turning point at fiscal year 1987â1988, just as Panagariya's (2004b) did.

7

Second, the “super-high” annual growth of 7.2 percent during 1988â1991 was preceded by significant, though partial reforms, especially in 1985â1986 and 1986â1987. It was also helped by significant depreciation of the rupee in the second half of the 1980s.

8

But more important, this growth was also driven by fiscal expansion and external borrowing that were not sustainable. Unsurprisingly, the surge ended in a balance-of-payments crisis in June 1991.

Even if we ignore the differences in growth rates in the 1980s and 1990s, the 1980s growth could not have been sustained without the post-1991 reforms.

Third, the shift to 8.2 percent growth during the nine years between 2003â2004 and 2011â2012 represents a significant jump in the growth rate following the post-1991 systematic reforms. Surely attributing this latest acceleration to some vague “attitudinal” change in the 1980s strains credulity.

In fact, many of the structural changes since 1991 have a direct link to the liberalizing reforms. Could the trade-to-GDP ratio have risen from 17 percent in 1990â1991 to more than 50 percent by the later 2000s without steady trade liberalization?

9

Could foreign investment have risen from $100 million in 1990â1991 to more than $60 billion in 2007â2008 without the liberalization of the foreign investment regime? Could the number of phones have risen from 5 million total at the end of 1990â1991 to new additions of over 15 million every month without the liberalization of telecommunications? Could automobile production have risen from 180,000 in 1990â1991 to 2 million in 2009â2010 without delicensing of investment and opening up to foreign investment? The list

goes on.

10

Policies matter; “changes in bureaucratic attitudes” in the absence of policy changes are ephemeral.

.

Critics also complain that the reforms have done precious little for the poor. The complaint has taken different forms depending on the time and context. Initially the claim was simply that reforms had not helped bring down poverty. But as the reforms and growth progressed through the 1990s and 2000s and evidence on poverty reduction accumulated, these claims shifted first to asserting that reforms had not led to acceleration in poverty reduction from that in the pre-reform period and then to arguing that they had failed to reduce the absolute number of poor. We address each of these claims below.

Empirical evidence showing that poverty failed to decline during the heyday of socialism and that it has seen a steady decline in the post-reform era is now incontrovertible.

Figure 3.2

shows the evolution of the proportion of those below the official poverty line, called the poverty ratio, at the national level from 1951â1952 to 1973â1974. The figure also includes the trend line for the poverty ratio during this period. It is evident from the figure that poverty fluctuated between 50 percent and 60 percent during this period with a slight

upward

trend. Because India had begun at a very low per capita income and grew at a very slow pace during the first twenty-five years of the development program, the country could make no dent in poverty whatsoever.