Why Growth Matters (28 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Finally, insofar as universal coverage is being increasingly connected to the recognition of the associated social goal as a legal right, the government must take a cautious view of such proposals. When universal coverage is close to reality, as, for example, in elementary education (see the next chapter), its recognition as a right may be a useful instrument of solidifying access to all. But when it is a distant goal, such recognition can be costly and counterproductive.

India faces a critical shortage of health-related human resources including doctors, nurse practitioners, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, and other health workers. Unqualified providers currently dominate the private sector, especially in rural areas. Improvements in access to health care, growth in population, and growth in personal income can be expected to further expand the demand for these personnel. On the supply side, shortages of medical personnel in the rest of the world due to aging populations are likely to accelerate the exit of these personnel from India. Therefore, in the absence of a major push to expand the supply, India will face massive shortages of medical personnel. Unfortunately, the problem does not seem to be on the radar screen of policy makers.

The need for rapid expansion in two areas is particularly acute. First, rural medical providers (RMPs) serve much of rural India. These practitioners have picked up some rudimentary skills either as employees in hospitals or while working as assistants to doctors but lack true qualifications for the job they do. Replacing the RMPs with proper doctors with MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery) degrees in a short period is an unrealistic goal even if it is desirable in the long run. Therefore, India needs to create a cadre equivalent to nurse practitioners in the United States. Even a one-year training program for the current RMPs may lead to a significant improvement in service and reduce risk to the patients.

Second, the expansion of the number of qualified MBBS doctors must begin right away. Recall that the Medical Council of India has treated medical education as its fiefdom. Its members are rumored to

have extracted large bribes for authorizing new medical colleges and for letting existing colleges stay open.

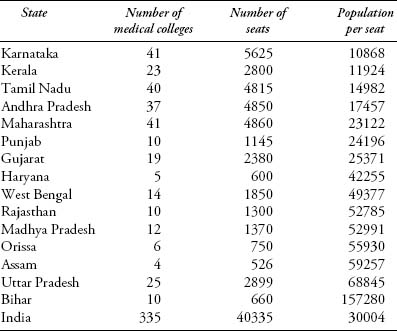

Table 16.1. Medical colleges and MBBS seats with states arranged in ascending order of population per MBBS seat

Note: Population in the last column is taken from Census 2011.

Source: Indian Medical Council,

www.mciindia.org

(accessed August 8, 2011)

The result of this tight control and associated corruption has been an overall shortage of doctors with MBBS. Only politically powerful and well-connected entrepreneurs, often politicians themselves, have been successful in getting approval for the opening of medical colleges in a handful of the states, especially Karnataka and Maharashtra.

Table 16.1

graphically brings out this point. Maharashtra and the four southern states currently account for 54 percent of medical colleges and 57 percent of MBBS seats in all of India. To dramatize the contrast, there is one MBBS seat per 157,280 people in Bihar, compared with one per 10,868 people in Karnataka.

India clearly needs to loosen the stranglehold of the Indian Medical Council on the expansion of medical colleges.

System

During the six decades since independence, health services in India have operated under a largely regulation-free environment. This has allowed health services to grow rapidly, with competition keeping the prices of not just everyday outpatient care but also surgical procedures relatively low. Absence of medical malpractice suits also has helped control costs. Likewise, the provision of only process and not product patents on medicines until 2005 has greatly facilitated the growth of a low-cost medicine industry.

This absence of regulation is by no means without cost. Reports of sales of fake medicines and their use by private providers as well as government-run hospitals are commonplace. RMPs and many providers in urban areas lack the required qualifications. Many hospitals and nursing homes are known to operate without a license or registration. Likewise, many diagnostic facilities exhibit poor standards.

Should India turn to regulation to combat these deficiencies? Our view is that a move toward systematic and substantial regulation at this point is premature. Once introduced, regulation in India has a way of quickly turning into a license-permit raj. Therefore, India must move cautiously in this direction. For now it may be best to go after egregious cases of malpractice and rely on informal oversight by NGOs and committees consisting of medical professionals and representatives of citizens at the village, block, district, and city levels. Regulation may be introduced gradually as medical services expand in the organized sector. But even then such regulation initially will be best left to local jurisdictions so that its design takes into account local conditions and constraints. Only after a sizeable organized sector emerges nationwide should full-fledged national-level regulation be considered.

Elementary Education

B

ecause higher education is critical to growth even while contributing to inclusion, its discussion belongs to Track I policies and was therefore taken up in

Part II

. In contrast, elementary education, though helpful in promoting and sustaining growth, is an important social objective in itself. Therefore, we consider it here as a part of Track II reforms.

Elementary education consists of primary (grades one through five) and middle (grades six through eight) school education. Here we first offer a brief review of progress toward universalizing elementary education and of the effectiveness of private versus public schools. We then follow up on the key policy issues for which the 2009 Right to Education Act provides the context.

The Indian Constitution, which came into effect on January 26, 1950, stated in one of its directive principles of state policy, “The State shall endeavor to provide, within a period of ten years from the commencement of this Constitution, for free and compulsory education for all children until they complete the age of fourteen years.” But this goal proved to be overly ambitious in view of the country's meager financial and physical resources, and the target date was repeatedly deferred, first to 1970 and then to 1980, 1990, and 2000.

1

It was not until the 86th Constitution (86th Amendment) Act of 2002 that education for children

between ages six and fourteen was promoted from a directive principle of the policy to a fundamental right. Even then the lack of financial resources held up the implementing legislation.

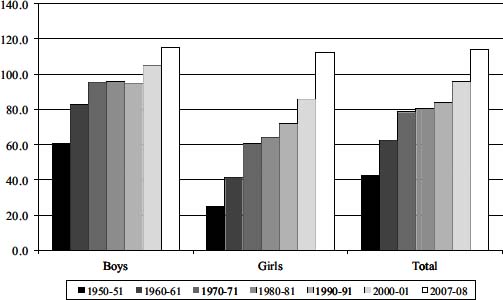

Figure 17.1. Gross enrollment ratios (grades one through five) for boys and girls

In the end, the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act of 2009 (or Right to Education Act for short) was passed in August 2009 and brought into force on April 1, 2010. Provisions of this act have been highly controversial.

Figures 17.1

and

17.2

show the gross enrollment ratio (GER) in primary (grades one through five) and middle (grades six through eight), respectively, by decade beginning in 1950â1951 and ending in 2007â2008, the latest year for which we have data. As previously noted, the GER measures the number of students enrolled at a particular educational level as a percentage of the population in the age group normally associated with that level. Because some students enrolled at the specified level may be older or younger than the typical age group, the ratio can exceed 100.

Figure 17.1

shows the enrollment ratios in primary education for girls, boys, and boys and girls combined. It may be noted that the ratio

remained below 100 for both boys and girls until 1990â1991 (fifth bar from left). Even in 2000â2001, it reached 100 only for boys and it almost certainly did not imply the inclusion of all boys in the age group six to eleven, because those enrolled included children older than eleven years and younger than six. As many as forty years after the original deadline in the Constitution, the government lacked the resources to achieve universal education even at the primary level.

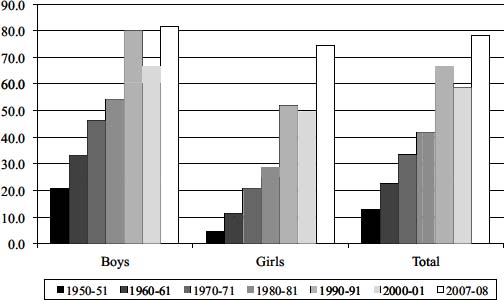

Figure 17.2. Gross enrollment ratios (grades six through eight) for boys and girls

Enrollment ratios in middle school consistently have been distinctly below those at the primary level and well below 100 even in 2007â2008 (

Figure 17.2

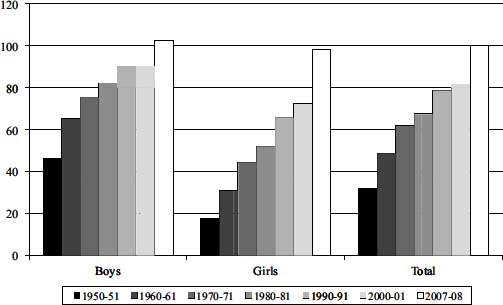

). Of course, this feature partially reflects the fact that many children ages eleven to fourteen are enrolled in primary school. This inference is supported by the enrollment ratios for grades one through eight combined, shown in

Figure 17.3

.

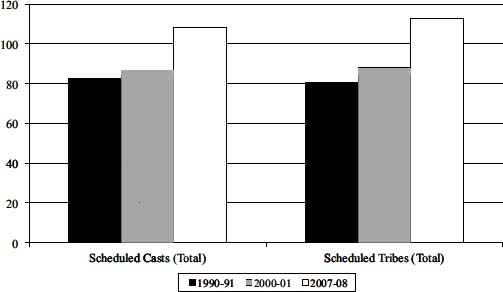

Progress has been made across all social groups including the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. We show the enrollment ratios for boys and girls combined in these groups for grades one through eight as a whole in

Figure 17.4

. For both the Scheduled Castes and Tribes, the

ratios had crossed the mark of 100 percent in 2007â2008. Thus, outcomes have improved across the board.

Figure 17.3. Gross enrollment ratio (grades one through eight)

Figure 17.4. Gross enrollment ratios for Scheduled Castes and Tribes, boys and girls