Why Growth Matters (31 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

In the course of finalizing this book, we benefited greatly from the comments by several panelists and participants at a prepublication discussion of the book that the National Council on Applied Economic Research (NCAER) and the Columbia Program on Indian Economic Policies jointly organized at the India International Centre in New Delhi on January 5, 2012. Our thanks go to Rajesh Chadha, Senior NCAER Fellow, who organized that event and oversaw its efficient execution.

The event brought together two panels, one consisting of intellectuals from various fields and the other composed of a group of leading journalists from Indian and Western newspapers. The comments and critiques we received at this meeting have resulted in many revisions.

In particular, we are grateful to Bibek Debroy (professor, Centre for Policy Research), Jay Panda (member, Lok Sabha), Manish Sabharwal (CEO, TeamLease), and Shekhar Shah (director general, NCAER), who spoke on the first panel, and Vikas Bajaj (

New York Times

), Sunil Jain (

Financial Express

), James Lamont (

Financial Times

), and T. N Ninan (

Business Standard

), who served on the second panel. Bina Agarwal (Institute of Economic Growth), Bornali Bhandari (NCAER), Rajesh Chadha (NCAER), Shashanka Bhide (NCAER), Rana Hasan (Asian Development Bank), Vijay Joshi (Oxford University), and Deepak Mishra (World Bank) offered additional comments from the floor.

The eminent historian Ramachandra Guha read all the chapters in

Part I

and provided detailed comments that have led to many improvements in the final draft. We also received positive feedback from Ashoka Mody of the International Monetary Fund and Swagato Ganguly of the

Times of India

, who read parts of the book.

A rather generous input came from a young scholar, Manish Kumar from Bihar. He researched virtually all publicly available volumes of speeches by Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, P. V. Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajapyee, and Manmohan Singh and provided us literally dozens of pages' worth of quotations to choose from. We are deeply indebted to him.

Zeenat Nazir, Shivam Srivastava, and May Yang provided excellent research assistance at various stages of the work.

The book generously draws on the scientific research undertaken by a number of leading scholars of the Indian economy as a part of the Program on Indian Economic Policies under the joint auspices of the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) and the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy (ISERP) at Columbia University. The program has been funded by a substantial grant from the Templeton Foundation. While the views expressed in the book are solely ours, we take this opportunity to thank the Templeton Foundation for funding the program and the ISERP staff, especially Michael Falco, Michael Higgins, Shelley Klein, Carmen Morillo, Andrew Ratanatharthorn, and Kristen Van Leuven, for their excellent logistical support.

Most of all, we acknowledge the splendid support that the Council on Foreign Relations provided to one of us (Bhagwati) for the research of this book. CFR President Richard N. Hass, Director of Studies James M. Lindsay, and Director of Maurice R. Greenberg Center for Economic Studies Sebastian Mallaby provided insightful comments on our manuscript, while Amy Baker and Patricia Dorff assisted with publication formalities.

Socialism Under Nehru

Now, it is well known, and we have often stressed this, that production is perhaps one of the most important things before us today: that is, adding to the wealth of the country. We cannot overlook other things. Nevertheless, production comes first, and I am prepared to say that everything that we do should be judged from the point of view of production first of all. If nationalization adds to production, we shall have nationalization at every step. If it does not, let us see how to bring it about in order not to impede production. That is the essential thing.

âPrime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in Constituent Assembly (Legislative), February 17, 1948

Nehru was a pragmatist first and a socialist second. The policy framework that emerged under him resulted principally from the objective of self-sufficiency. In Nehru's conception, the pursuit of self-sufficiency meant progressive reduction in the dependence on the external markets for either the sales of Indian goods abroad or the purchase of foreign goods to satisfy domestic needs.

1

India having just emerged from the colonial rule, this seemed an eminently reasonable objective.

Yet, what is reasonable is not necessarily rational. Self-sufficiency became an argument for import substitution and policies (such as protection) directed at promoting it.

2

It meant the recalibration of the production basket to domestic needs. If India needed bicycles, it must produce bicycles as well as the steel going into them. If it needed fertilizer, it must produce fertilizer and the chemicals going into them. And, of course, it must also produce the machines necessary to produce the bicycles, steel, fertilizers, and chemicals.

There being general agreement at the time that the private sector lacked resources to invest in the heavy-industry sectors consisting of such items as steel and machinery, it was also decided that the public sector would enter them in a major way.

3

But reinforcing this argument for the public sector's expansion was Nehru's political belief in the desirability of progressive expansion of the public sector. In this regard he was a Fabian socialist who did not favor “painful” nationalization but relied instead on a progressive and “painless” shift in investment over time to yield a larger share of the public sector in production in the economy. It was a policy of painless, “asymptotic” achievement of an economy dominated by public ownership of the means of production.

The last argument explains why the public sector was viewed not just as

substituting

for the private sector that could not undertake expansion in the favored import-substituting sectors. In fact, the goal of expanding the public sector relative to the private sector progressively over time also led to the policy of

reserving

certain sectors exclusively for the public sector. In turn, that meant that government monopolies were created, which had unfortunate consequences for efficiency since eliminating domestic competition would be joined later by eliminating import competition as well.

In addition, one can detect some concern, starting in Nehru's administration, that the planners had to direct investment selectively to sectorsâthat there were social payoffs in some sectors and not in others. This meant that sectoral quantities in the planning exercises were increasingly taken as not just indicative but as firm targets, to be implemented by a licensing system that would restrain investment in the less-favored sectors.

4

Therefore, investment licensing for large firms was adopted to allocate private investments according to the national priorities.

On the external front, the policy regime during the 1950s was remarkably open. Tariffs were low, and though import licensing had been inherited from the Second World Warâera controls, licenses were leisurely issued. Consumer goods imports were allowed and the importer did not have to be the actual user.

5

On the foreign investment front,

Nehru fought off the domestic private industry, leftist parties, and radical socialists within the Congress to maintain and promote a liberal regime. He refused to nationalize the foreign firms and accorded them national status. He also permitted the repatriation of profits and dividends of foreign companies abroad. As late as the early 1960s, the government actively sought foreign investment in heavy electrical equipment, fertilizer, and synthetic rubber, sectors in which the public sector had been active.

Investment licensing also remained relatively liberal with the decisions on the applications made without undue delay in the 1950s. This is partially evidenced by the near-absence of complaints by private entrepreneurs and also the rapid expansion of the private sector. The share of the public sector in the total investment in the First Five-Year Plan was 46 percent. The Second Plan set the explicit goal of raising this share to 61 percent. But because private-sector investment greatly exceeded its projected level, the plan fell well short (54 percent) of the target in proportionate terms even while substantially achieving it in absolute terms. The Third Plan sought to push the share to 64 percent but once again fell short at approximately 50 percent.

The key factor behind tightening the import and investment licensing regimes was not ideological, but the balance of payments crisis in 1957â1958. That crisis led the finance ministry to introduce foreign-exchange budgeting beginning in the second half of 1958. This required estimating the expected availability of foreign exchange in each forthcoming six-month period and then allocating it across various uses. Hereon, each investment-license application had to provide sufficient technical details to allow the evaluation of the foreign-exchange burden it would impose for machinery and raw material imports. The license was issued only if the product it sought to produce was judged to be sufficiently important to justify the allocation of the needed foreign exchange.

While the grip of the license-permit raj became significantly tighter during the first half of the 1960s, radical socialists within the Congress and outside had at best limited salience while Nehru lived. Indeed, toward the end of his administration, several right-of-center politicians

gained influence in the Congress organization while hard-core socialists, such as Krishna Menon and K. D. Malviya, were forced out of the union cabinet.

The “second phase” of socialism under Indira Gandhi, the “accidental” prime minister, was unfortunately far less pragmatic, as we note in the text: it changed the course of Indian policy until the reforms began in earnest in 1991.

Measuring Inequality:

The Gini Coefficient

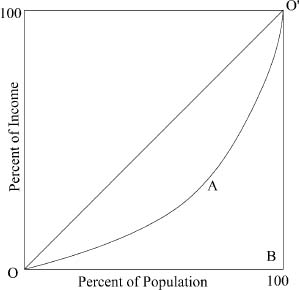

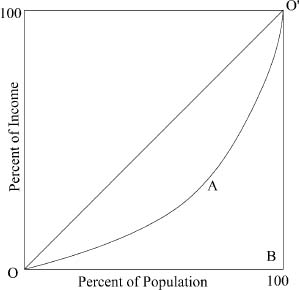

The Gini coefficient is the most common measure of the distribution of expenditure, income, wealth or another attribute within a given population. Since it is common to speak in terms of income distribution among households within a population, we explain the measure in terms of inequality of income across households. The value of Gini varies between 0 and 1, with 0 representing a situation of perfect equality, such that income is identical across all households, and 1 representing a situation of extreme inequality whereby all income is concentrated in a single household. Between 0 and 1, higher values of the Gini are associated with higher levels of inequality.

The logic behind the Gini and its limitations can be explained with the help of the Lorenz curve (explained below), shown in Figure A2.1. On the horizontal axis, we arrange the households in the rising order of their incomes. Therefore, the household with the lowest income is the nearest to the origin and the one with the highest income is the farthest. We “normalize” the total number of households to 100. On the vertical axis, we measure the cumulative incomes of households as percent of the total income of the population. The curve representing the cumulative percentage incomes of households, depicted by OAO' in Figure A2.1, is called the Lorenz curve. A point on the Lorenz curve represents the percentage of the total income by households up to that point. The Lorenz curve originates at the origin since 0 percent of the households account for 0 percent of the population income. Likewise, the curve terminates at a point showing the values of 100 on both horizontal and

vertical axes since 100 percent of the households must account for 100 percent of the population income.

Figure A2.1. The Lorenz curve

The Gini coefficient equals the area between the diagonal OO' and the Lorenz curve divided by the triangle OBO'. It is immediately obvious that if the Lorenz curve coincides with the diagonal OO', the Gini coefficient becomes 0 since the area between the diagonal and the Lorenz curve is zero in this case. Alternatively, if the Lorenz curve coincides with triangle OBO', the Gini coefficient becomes 1. In this case, the area between the Lorenz curve and the diagonal is triangle OBO' and its ratio to triangle OBO' is 1. In all other cases, the value of the Gini coefficient is strictly between 0 and 1.