Why Growth Matters (14 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Â

â¢

Â

Again, if the Kerala model is that much more effective, it should be able to overcome a higher barrier and still deliver a superior outcome. In effect, resorting to the argument that the performance looks poorer because a higher starting point gives the state a handicap seems like an admission that the model is as mortal as any after all.

Â

â¢

Â

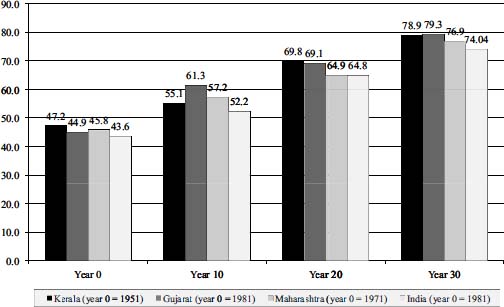

Finally, there is an objective way to test whether the higher starting point was truly a handicap or the Kerala model has indeed been overrated. We can accomplish this by assigning Kerala and the other states the same starting point and then evaluating who wins the race. In

Figure 5.7

, we depict the progress in literacy in Kerala, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and India with their starting years being 1951, 1981, 1971, and 1981, respectively. These starting years assign the four entities as close a starting literacy rate as data would permit.

12

We depict the literacy rates at the end of three decades since this is as far as we can go for Gujarat and India, whose starting points are both 1981.

Gujarat unambiguously beats Kerala: it starts more than 2 percentage points below Kerala in year 0 but ends up a hair's breadth above it in year 30. Both Maharashtra and India as a whole perform only slightly worse than Kerala. For example, Maharashtra is 1.4 percentage points below Kerala in year 0 and 2 percentage points below it in year 30. India as a whole performs similarly.

The discussion up to this point has focused on the developments in health and education in Kerala in the postindependence era. An interesting and important unanswered question, however, is what accounts for Kerala's having acquired its gigantic lead over much of the rest of India at independence. Even here the conventional story that this was to be attributed to the movements for social justice and social programs by the rulers of Travancore and Cochin is quite incomplete. Careful scrutiny gives way to a more complex explanation that includes important links of Kerala's early success to globalization.

While we have been unable to find reliable accounts of developments in the health sector in pre-independence Kerala, Robin Jeffrey (1992), who has spent many years living in various parts of India since the 1960s, offers a detailed account of the socio-economic-political developments that contributed to the spread of literacy in Kerala in the second half of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth. Based on his account, four key factors can be highlighted.

Figure 5.7. Comparing progress in literacy rates in Kerala to those in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and India beginning at approximately the same level

Source: See

Figure 5.4

First, the rulers in Travancore and Cochin played an important role in the spread of education. Travancore Maharajas began investing in the spread of vernacular primary schools in the 1860s. Maharajas of Cochin followed suit beginning in the 1890s. Their objective was to spread modern knowledge to the widest circle of people through the use of the mother tongue, Malayalam. Children of upper-caste Hindus and Syrian Christians dominated the government schools till the end of the nineteenth century. But by the beginning of the twentieth century, both Travancore and Cochin offered concessions to lower-caste students whose numbers expanded rapidly.

Second, the culture of old Kerala, which included the importance assigned to women by matrilineal tradition among several communities, was

conducive to the spread of education. Even before Travancore Maharajas got actively involved in education, an extensive network of village schools had existed. Landed high-caste Hindu and Syrian Christian families supported these schools. The wealth enjoyed by these families allowed them to send their children to schools rather than to work. Nayars and other matrilineal groups sent girls to the schools as well. One measure of the contribution made by this culture of education is that Malabar, the remaining Malayalam-speaking district, which was administered by the Madras presidency and had no princely government to promote education, never fell below third place within the presidency overall and consistently ranked top in female literacy.

Third, caste- and religion-based groups also played some role in the spread of education. Among the upper-caste groups, the Nair Service Society, which was founded in 1914, promoted education through the so-called Nair schools. The Sri Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam that the widely revered Sri Narayan Guru founded in 1903 played the same role among the lower-caste Ezhavas, though with less success since the community was much poorer and lacked resources. The Christian missionaries also helped accelerate the process of the spread of education. Protestant missionaries made their debut in Travancore with the arrival of Tobias Ringeltaube in 1806. He quickly got permission from the Maharaja to open a few schools. According to Jeffrey (1992, p. 97), by the middle of the nineteenth century, Travancore had a higher density of Protestant missionaries than any other part of India. They not only actively promoted literacy directly, especially among the lower-caste Nadars, but also greatly influenced the largest Christian group, the Syrian Catholics, who started establishing formal, literacy-oriented schools beginning in the early 1880s.

The fourth and last factor, which rarely is highlighted in the spread of education in Kerala prior to independence, is economic. A necessary condition for all of the above agents of the spread of literacy to succeed was the availability of necessary resources. Those building schools had to have the necessary revenues and the parents sending children to school had to have enough income to make ends meet without their

children's labor. To sustain the process, it was also necessary that those acquiring education would have prospects for jobs commensurate with their qualifications.

This is where globalization played a key role. Roman coins commonly found in Kerala testify to its trade links abroad through pepper and cardamom exports going back 2,000 years. Jeffrey (1992) suggests that this trade link is a plausible explanation for the early presence of Jews, Muslims, and Christiansâthey came to trade and chose to stay: “Long before Britain or America, Kerala was a part of a âworld economic system'” (p. 72).

Beginning in the 1830s, cash crops saw a boom in Kerala. Europeans began establishing plantations to grow crops of interest to Europe and America. First came coffee; after its destruction by a leaf disease in 1880 came tea; and in the 1920s, cashews. Coconut, with its varied uses, turned into the most important crop, with trees springing up everywhere. Jeffrey (1992) quotes the Collector of Malabar in the mid-1930s as reporting to his superiors, “All but the poorest Malabar

ryots

[peasants] have their own compounds of fruit trees” (p. 73). Since coconut could not serve as a staple food, it had to be converted into money and money into food. This contributed in a big way to both the growth of trade as well as the conversion of Kerala into a cash economy. Jeffrey (1992) writes, “In this way, cash-oriented agriculture spread. Before about 1810, Kerala was, to be sure, part of a world market, but few Malayalis had to deal with it directly; but by the 1920s, few Malayalis could avoid it” (p. 73).

The growth of commercial houses and estates created job opportunities for the educated, making education attractive. Cash crops also served as an excellent source of revenues to finance schools for the state as well as larger landowners. Prosperity brought by the spread of cash crops enabled civic organizations to raise funds to open schools as wellâan important link of the early spread of education in Kerala to markets and globalization.

The historic origin of preindependence success of Kerala therefore owes as little to the Kerala model as does its postindependence performance.

.

This myth is the mirror image of the previous one, whereby rapid growth in Gujarat is alleged to have not translated into rapid progress in social indicators. The problem once again lies in inference on the basis of the

levels

rather than the progress achieved during the high-growth phase. Gujarat began with low social indicators but its progress has not been poor by any means.

13

We have already alluded to the superior performance of Gujarat in raising literacy rates in our discussion of the Kerala model. We saw that when we take approximately the same starting level of literacy, as in

Figure 5.7

, the gains made by Gujarat in three decades exceed those made by Kerala, Maharashtra, and the India-wide average. We may additionally note that when compared with these same entities, Gujarat made by far the largest percentage-point gains in literacy between 1951 and 2011.

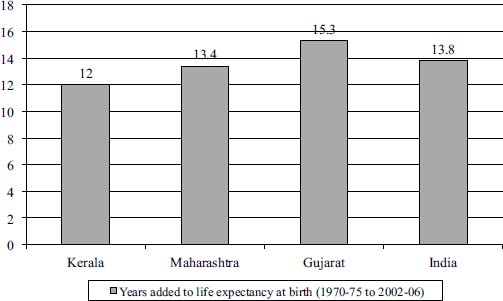

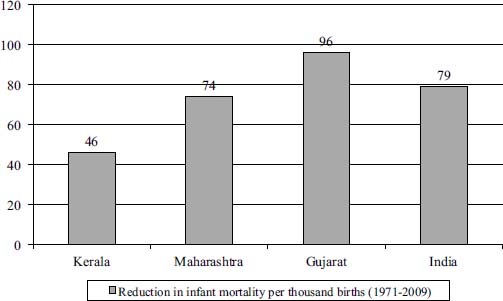

This comparison of the gains by Gujarat in literacy carries over to the key indicators of health.

Figures 5.8

and

5.9

, which show the gains in life expectancy measured in the number of years and decline in infant mortality per 1,000 live births, respectively, illustrate this fact. We have comparable data on life expectancy beginning in 1970â1975 and ending in 2002â2006. The gains of Gujarat over this period at 15.3 years exceed those of Kerala, Maharashtra, and the India-wide average. The available data on infant mortality range from 1971 to 2009. During this period, Gujarat lowered its infant mortality rate by 96 per 1,000 live births relative to 74 for Maharashtra and 46 for Kerala.

Figure 5.8. Additions to life expectancy in years: 1970â1975 to 2002â2006

Source: See

Figure 5.5

Figure 5.9: Reductions in infant mortality per thousand live births: 1971â2009

Source: See

Figure 5.5

Yet Other Myths

W

e have now seen that growth, poverty, inequality, education, and health are the key subjects on which critics have tried to mobilize opposition to reforms. But they have failed. So have turned to a potpourri of yet other myths. Chief among them are the following four.

.

A common activist objection to liberalization in general and the use of genetically modified seeds in particular has been that they lead to suicides by farmers. The view found its most dramatic expression at the 2003 summit of the World Trade Organization in Cancun, Mexico, where activist farmer Lee Kyung-hae of South Korea climbed the barricade while holding a banner reading “WTO kills farmers” and stabbed himself to death. Recent farmer suicides in India have properly been an emotionally charged issue in India, in particular. The country therefore confronts opposition to reforms and the use of new genetically modified and

Bacillus thuringiensis

(BT) seeds.

Influential journalists such as Sainath (2009) of the newspaper the

Hindu

and activists such as Vandana Shiva (2004) have led the opposition to the new seeds on the grounds that they lead to “agricultural suicides.”

1

But the evidence they provide fails to substantiate their case.

Suicide is a complex phenomenon with multiple causes and, in the case of farmer suicides, even the basic facts are treacherous to analyze.