Why Growth Matters (18 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Ultimately the flight from unskilled labor is at the heart of the unusually heavy concentration of Indian workforce in small firms, especially in the labor-intensive industries. A preponderance of small firms in turn hampers export performance since such firms have no incentive to invest in searching for and developing large markets abroad. Instead, it is far more cost-effective for them to sell their wares in the local market.

In recent important research, Hasan and Jandoc (2012) analyze the firm-size distribution of some major sectors, such as apparel, automobiles, and auto parts, that represent the highly labor- and capital-intensive sectors, respectively.

5

Their work sheds new light on the structure of Indian manufacturing that we have already sketched.

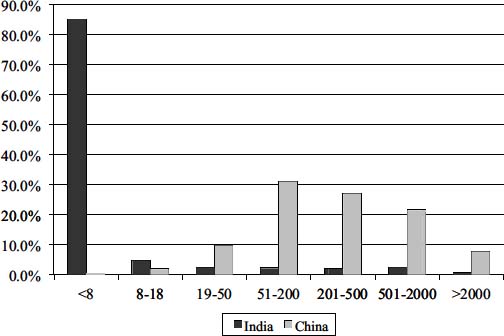

Combining the data on the firms in the organized as well as unorganized manufacturing, Hasan and Jandoc (2012) first show that an astonishing 84 percent of the workers in all manufacturing in India were employed in firms with forty-nine or fewer workers in 2005. Large firms, defined as those employing two hundred or more workers, accounted for only 10.5 percent of manufacturing workforce. In contrast, small-and large-scale firms employed 25 percent and 52 percent of the workers, respectively, in China in the same year.

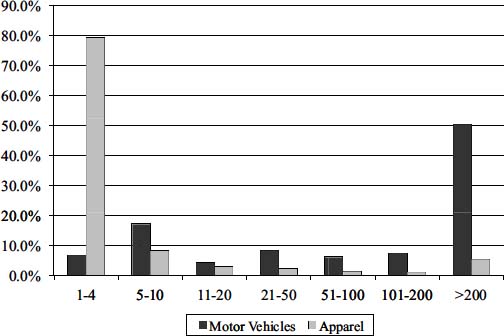

Upon disaggregation by sectors, Hasan and Jandoc find that the firm-size distribution in India is skewed toward even smaller enterprises in the labor-intensive sectors, with the large firms concentrated in the capital-intensive sectors. Thus, workers in the highly labor-intensive apparel sector are concentrated almost entirely in the small firms, with 92.4 percent of workers in firms with fifty or fewer workers. This distribution contrasts sharply with that in China where medium-and large-scale firms account for a gigantic 87.7 percent of the apparel employment (see

Figure 8.2

). The firm-size distribution in apparel in India also contrasts sharply with the more capital-intensive auto and auto-parts sector within the country, in which large-scale firms employed 50.3 percent of all workers in the sector in 2005 (see

Figure 8.3

).

Figure 8.2. Employment share by firm size in apparel in China and India, 2005

Source: Hasan and Jandoc (2010)

The near-absence of medium and large firms in apparel, especially when compared with China, is clearly linked to this sector's poor export performance. The inability to massively capture the export markets in this major sector with comparative advantage is in turn linked to the poor performance of labor-intensive manufacturing and therefore manufacturing in general. The ultimate key to understanding why growth has not been as inclusive in India as in South Korea, Taiwan, and China remains the absence of large-scale firms in the labor-intensive sectors in India.

Figure 8.3. Employment shares by firm size in apparel versus motor vehicles and motor parts, 2005

Source: Hasan and Jandoc (2012)

Why have the reforms so far not done more to produce medium- and large-scale firms in the labor-intensive sectors and hence to create many more well-paid jobs in the economy while boosting exports? The most plausible explanation is that the reforms have been confined principally to product markets (with a limited attention paid to capital-market liberalization). Multiple layers of regulation in the remaining two major factor markets, labor and land, continue to discourage the growth of manufacturing in general and of unskilled-labor-intensive products in particular.

The past reforms have removed four important layers of regulation in the product and capital markets:

Â

â¢

Â

Investment licensing, which prevented large firms from investing outside of the highly capital-intensive “core” industries, has been eliminated

Â

â¢

Â

Protection, which had prevented firms from exploiting large world markets, has been substantially removed from industry and services, though agriculture remains heavily protected

Â

â¢

Â

The door to foreign firms with state-of-the-art know-how and with knowledge of and links to the world market has been opened

Â

â¢

Â

Above all, the reservation of virtually all labor-intensive products for exclusive manufacture by small enterprises has been effectively ended

6

Many analysts expected that these reforms, especially the last one, would pave the way for the emergence of the large-scale firms in the labor-intensive sectors and lead to a boom in labor-intensive exports. But this did not happen. Why?

Initially the lack of response in apparel, the labor-intensive sector with the largest world market, could have been attributed to the manner in which India had implemented the multifiber export quota. The Indian policy was to give the unused export quota not to existing users but to new applicants. This meant that the existing successful firms could not expand to take advantage of the end to small-scale industries reservation. But with the multifiber-arrangement quotas having ended in 2005 as part of the successful closure of the Uruguay Round on multilateral trade negotiations, this explanation no longer holds.

The true explanation lies instead in the fact that additional layers of regulations and barriers remain that discourage the emergence of large-scale labor-intensive manufacturing in India. The dominant cause is a highly inflexible labor market, which makes the cost of labor in the formal sector excessively high.

In addition, three complementary factors impede the emergence of large-scale labor-intensive manufacturing: the absence of modern bankruptcy laws permitting smooth exit in case of failure; a highly distorted land market; and poor infrastructure. Remarkably, despite the lapse of two decades since economic reforms began in earnest, there has been no attempt whatsoever to undertake the reforms of antiquated labor laws that affect all these issues, with new legislation being generally confined to giving yet more social protections to workers.

Labor markets in India offer a stark contrast to those in Taiwan, South Korea, and China during their rapid-growth phases. In addition to openness and high savings rates, highly flexible labor markets characterized these latter countries. Unions were absent or weak and for all practical purposes strikes were illegal. Firms also had full rights to hire and fire workers. In contrast, regular workers in the organized sector in India have had legal protections exceeding those in most developed countries and unheard of in the developing world in the early stages of development.

The burden labor laws impose on entrepreneurs cannot be fully appreciated without a detailed discussion of some of the laws, a task we undertake in this section. Under the Indian Constitution, labor is a “concurrent” subject, meaning that both the center and the states can enact laws in this area. Neither has exactly been shy about exercising that right.

Thus the Ministry of Labor lists as many as fifty-two independent central government acts in the area of labor.

7

According to Amit Mitra, former secretary general of the Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and industry and now finance minister in the new Mamata Banerjee government in West Bengal,

8

an additional 150 state-level laws exist in India.

9

This count places the total number of labor laws in India at approximately two hundred. Compounding the confusion created by this multitude of laws is the fact that they are not entirely consistent with one another, leading a wit to remark that you cannot implement Indian labor laws 100 percent without violating 20 percent of them.

10

The 1926 Trade Unions Act requires firms with seven or more workers to allow them to form a trade union.

11

This perhaps gives firms with six or fewer workers the most labor-market flexibility. For instance, the act empowers trade unions to strike and represent their members in labor courts in disputes with the employers. Because union officials can be outsiders, prospects for such disputes rise with the formation of unions. Firms can thus minimize labor-related problems as long as they are smaller than seven workers. The dominance of tiny firms in the apparel sector we saw earlier may well have something to do with this fact.

Factories engaged in manufacturing and employing ten or more workers, regardless of whether these factories use power, are subject to the 1948 Employees' State Insurance Act. State governments may also extend the provisions of the act to other industrial, commercial, or agricultural establishments. For employees, hired at a wage up to 10,000 rupees a month, the act provides benefits related to sickness, maternity, disability, dependents, old-age medical care, funeral, employment injury, and rehabilitation.

On the other hand, manufacturing units, with ten workers using power and with twenty workers even if not using power, are subject to yet another piece of legislation: the 1948 Factories Act. This act limits the maximum hours of work per week to forty-eight; limits work without a day of rest to ten days; requires a paid holiday for each twenty days of work; prohibits the employment of children younger than fifteen; and bans the employment of women for more than nine hours per day and between 7 p.m. and 6 a.m.

The requirements extend to additional demands: the factory premises are to be kept clean, including whitewashing every fourteen months and repainting every five years; proper disposal of waste is mandated; adequate and separate restrooms for men and women are required; and an uninterrupted supply of drinking water must be made available. The act also makes extensive provisions for worker safety, including fencing of machines and moving parts of machines; the use of goggles to protect against excessive light and infrared and ultraviolet radiation; precautions against fire; and limits on the weight permitted to be carried by women and young persons.

Moreover, the mandated requirements rise as the number of employees rises. For example, at 150 workers, lunchrooms must be provided; at 250 workers, a canteen must be available on factory premises. And if the firm employs 30 women, a day-care center must be made available.

Aside from the fact that many of these regulations are costly to implement and increase the cost of hiring more labor, the Factories Act also generates considerable paperwork. For instance, each factory must maintain registers of attendance, of adult workers hired, of the dates of lime washing and painting, of leave granted with wages, provision of

health care (in case of persons employed in occupations declared hazardous), and the incidence of accidents. It must also file information to appropriate authorities on half-yearly and annual returns.

Again, all establishments with twenty or more workers, whether in industry or services, are further subject to the 1952 Employees' Provident Fund and Miscellaneous Provisions Act. This act provides three types of benefits: a contributory provident fund, pension benefits to the employees and his family members, and insurance cover including cash support during times of sickness, maternity benefits, payments in case of disability arising from work-related accidents, and medical expenses.

12

But we have hardly scratched the surface of the labor laws that suffocate Indian entrepreneurs. Indeed, several other legislations impose a variety of requirements, some applying to all establishments and others to those with some threshold number of workers. Often the central legislation gives states the authority to extend the provision of the legislation to establishments not covered by it, which states use unhesitatingly. Among key central legislations are the 1961 Maternity Benefit Act, applicable to all factories, establishments, and shops depending on the state government; the 1948 Minimum Wages Act, which requires state governments to fix the minimum wage in specified employments; the 1965 Payment of Bonus Act, applicable to all firms registered under the 1948 Factories Act and establishments with twenty or more workers; the 1972 Payment of Gratuity Act, applicable to all factories and establishments with ten or more workers; the 1923 Workmen's Compensation Act, which applies to all workers; and the 1946 Industrial Employment (Standing Order) Act, which applies to all industrial establishments with one hundred (in some states fifty) or more workers.