Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (35 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

One of the things I commonly hear when I tell people about Holocaust deniers is that they must be raving racists or nutty fools on the lunatic fringe. Just who would say the Holocaust never happened? I wanted to find out, so I met with some of them to allow them to present their claims in their own words. In general, I found these deniers relatively pleasant. They were willing to talk about the movement and its members quite openly, and they generously provided a large sampling of their published literature.

After World War II, revisionism began in Germany with opposition to the Nuremberg trials, typically seen as "victor's trials" that were hardly fair and objective. Revisionism of the Holocaust itself took off in the 1960s and 1970s with Franz Scheidl's 1967

Geschichte der Verfemung Deutschlands

(In Defense of the German Race), Emil Aretz's 1970

Hexeneinmakins einer Liige

(The Six Million Lie), Thies Christophersen's 1973

Die Auschwitz-Liige

(The Auschwitz Lie), Richard Harwood's 1973

Did Six Million Really Die?,

Austin App's 1973

The Six Million Swindle,

Paul Rassinier's 1978

Debunking the Genocide Myth,

and the bible of the movement, Arthur Butz's 1976

The Hoax of the Twentieth Century.

It is in these volumes that the three pillars of Holocaust denial—no intentional genocide by race, gas chambers and crematoria not used for mass murder, many fewer than six million Jews killed—were crafted.

Except for Butz's book, which stays in circulation despite being disorganized beyond repair, these works have all given way to

the Journal of Historical Review (JHR),

the voice of the Institute for Historical Review (IHR). The institute's journal, along with its annual conference, has become the hub of the movement, which is populated by a handful of eccentric personalities including IHR director and

JHR

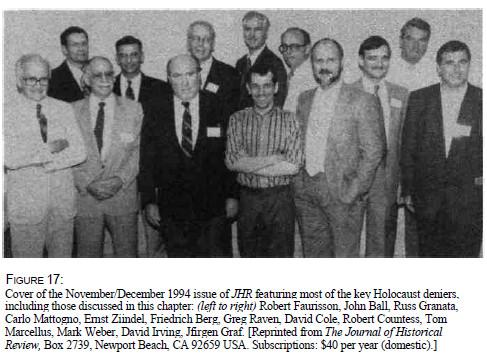

editor Mark Weber, author and biographer David Irving, gadfly Robert Faurisson, pro-Nazi publisher Ernst Ziindel, and video producer David Cole. (See figure 17.)

Institute for Historical Review

In 1978, IHR was founded and organized primarily by Willis Carto, who also published

Right

and

American Mercury

(considered by some to have strong antisemitic themes) and now runs Noontide Press, publisher of controversial books including those denying the Holocaust. Carto also runs Liberty Lobby, which is classified by some as an ultra-right-wing organization. In 1980, IHR's promise to pay $50,000 for proof that Jews were gassed at Auschwitz made headlines. When Mel Mermelstein met this challenge, headlines and later a television movie detailed his collection of the award and an additional $40,000 for "personal suffering." IHR's first director, William McCalden (a.k.a. Lewis Brandon, Sandra Ross, David Berg, Julius Finkelstein, and David Stanford), was fired in 1981 due to conflicts with Carto and was succeeded by Tom Marcellus, a field staff member for the Church of Scientology who had been an editor for one of the church's publications. When Marcellus left IHR in

1995, JHR's

editor, Mark Weber, took over as its director.

Since the 1984 fire-bombing that destroyed its office, IHR is understandably cautious about revealing its location to outsiders. Situated in an industrial area of Irvine, California, the office has no sign and its glass door, entirely covered with one-way mirror coating, is dead-bolted at all times; one must be identified and admitted by the secretary working in a small office in front. Inside, there are several offices for the various staff members and a voluminous library. Not surprisingly, World War II and the Holocaust are the prime foci of its resources. In addition, IHR has a warehouse filled with back issues

of JHR,

pamphlets, and other promotional materials, as well as books and videotapes, all part of a catalogue business that, together with subscriptions, accounts for about 80 percent of revenues, according to Weber. The other 20 percent comes from tax-free donations (IHR is a registered nonprofit organization). Whatever funds the institute was receiving through Carto dried up after the 1993 falling out with (and subsequent filing of lawsuits against) the founder of IHR.

Before the break with Carto, IHR leaned heavily on the "Edison money," a total of about $15 million willed by Thomas Edison's granddaughter, Jean Farrel Edison. According to David Irving (1994), about $10 million of that money apparently was lost by Carto "in lawsuits by other members of the family in Switzerland" and the remaining $5 million was made available to Carto's Legion for the Survival of Freedom. "From that point on it vanishes into uncertainty. Certain sums of money have turned up. A lot of it is in a Swiss bank at present."

When the institute's board of directors voted to sever all ties with him, Carto apparently did not take it lying down. According to IHR, among many other things, Carto has "stormed IHR's offices with hired goons" and put out "the fantastic lie that the Zionist ADL [Anti-Defamation League] has been running IHR since last September" (Marcellus 1994). On December 31, 1993, IHR won a judgment against Carto. They are now suing him for damages incurred during his raid on the IHR office, which destroyed equipment and ended in fisticuffs, as well as for other moneys that, Weber claims, went "to Liberty Lobby and other Carto controlled enterprises. Probably the money has been frittered away by Carto but we are trying to track this down" (1994b).

In February 1994, Director Tom Marcellus sent a mass mailing to IHR members with "AN URGENT APPEAL FROM IHR" because it had "been forced to confront a threat to the editorial and financial integrity. . . that in the past several months has drained, and continues to drain, literally tens of thousands of dollars from our operations." Without help from its members, Marcellus wrote, "IHR may not survive." Carto was accused of becoming "increasingly erratic," both in personal matters and in business, and of involving "the corporation in three costly copyright violations." Most interesting, and in keeping with deniers' current attempts to disassociate themselves from earlier antisemitic connections and present themselves as objective historical scholars, the mailing condemned Carto for changing "the direction of IHR and its journal from serious, nonpartisan revisionist scholarship, reporting, and commentary to one of ranting, racialist-populist pamphleteering" (Marcellus 1994).

David Cole believes that the post-Carto "IHR is going to have to depend a lot more on journal and book sales" and thus on their right-wing, antisemitic backers:

In order to keep the IHR in the black they have had to cater to the far right. I think if you were to look at their book sales you would see that some of the more complex, really solid historiographical works probably don't sell as well as Henry Ford's

International Jew

or the

Protocols of Zion,

or some of the other things they sell. If they had to rely on the sales of Holocaust revisionist works alone they'd be screwed. They have to cater to the money. There are a lot of elderly people with money saved or with social security checks, who want to spend the last years of their life fighting the Jews. Bradley [Smith] can get checks for $5,000, $7,000, $3,000. These people are very, very wealthy, and completely anonymous. There is a lot of money to be made by getting a really good ideological mailing list and the IHR has one that caters mainly to people of the far right. (1994)

As of 1996, IHR still holds conferences (attendance about 250),

JHR

continues to be published (circulation about 5,000 to 10,000), and promotional literature and book and videotape catalogues are regularly mailed out. Whether IHR survives the break with Carto or not, we must remember that the denier movement is not a homogeneous group held together by this organization alone.

Mark Weber

With the possible exception of David Irving, in the denier movement Mark Weber may know the most about history and historiography. Some people have claimed that Weber's master's degree in modern European history from Indiana University is fake, but I called the university and confirmed that his degree is real. Weber arrived on the denier scene when he appeared as a defense witness at Ernst Zxindel's "free speech" trial in 1985. Weber denied any racist or antisemitic feelings and claimed, "I don't know anything more about the neo-Nazi movement in Germany than what I read in the papers" (1994b). Weber, however, was once the news editor

of National Vanguard,

the voice of the National Alliance, William Pierce's neo-Nazi, antisemitic organization. Weber also does not repudiate comments he made in a 1989 interview published by the

University of Nebraska Sower

about the United States becoming "a sort of Mexicanized, Puerto Ricanized country" due to the failure of "white Americans" to reproduce adequately. (Not that this sentiment is particularly unusual in our ever-increasingly segregationist society. Weber's wife told me at the 1995 IHR conference that these white guys should quit complaining about other races breeding too much and have more children themselves.) And on February 27, 1993, Weber was the object of a Simon Wiesenthal Center sting operation, secretly filmed by CBS, in which researcher Yaron Svoray, calling himself Ron Furey, met with Weber in a cafe to discuss

The Right Way,

a bogus magazine created to trick neo-Nazis into revealing their identities. Weber quickly figured out that Svoray "was an agent for someone" and "was obviously lying," and left (1994b). Subsequently, Weber was portrayed in an HBO movie about neo-Nazis in Europe and America, and he says that the Wesenthal version of the event is greatly distorted.

Such clandestine operations by the Simon Wiesenthal Center raise many troubling questions. Nonetheless, one must wonder why, if he is trying to distance himself from the neo-Nazi fringe of denial (as he claims), Weber would agree to such a meeting. Even David Cole, who is his friend, admits that "Weber doesn't really see any problems with a society that is not only disciplined by fear and violence but also where a government feeds its people lies in order to keep them well-ordered." Says Cole, "Deniers criticize the Jews for lying to its people or the world, and yet a lot of these same revisionists will speak very complimentarily of what the Nazis did in feeding their people lies and falsehoods in order to keep morale up and to keep this notion of the master race" (1994).

Weber is extremely bright and very personable, and one could believe that he might be capable of good historical scholarship if he ended his fixation on Jews and the Holocaust. He knows history and current politics and is a formidable debater on any number of subjects. Unfortunately, one of these subjects is Jews, whom he continues to generalize into a unified whole and to fear as a unified threat to American and world culture. Weber cannot seem to discriminate between individual Jews, whose actions he may like or dislike, and "the Jews," whose supposed actions he generally dislikes, and he cannot seem to grasp the innate complexity of contemporary culture.

David Irving

David Irving has no professional training in history, but there is no disputing that he has mastered the primary documents of the major Nazi figures, and he is arguably the most historically sophisticated of the deniers. Although his attentions have spanned the Second World War—he is the author of histories such as

The Destruction of Dresden

(1963) and

The German Atomic Bomb

(1967), as well as biographies including

The Trail of the Fox

(1977, on Rommel),

Hitler's War

(1977),

Churchill's War

(1987),

Goring

(1989), and

Goebbels: Mastermind of the Third Reich

(1996)—his interest in the Holocaust is growing ever stronger. "I think that the Holocaust is going to be revised. I have to take my hat off to my adversaries and the strategies they have employed—the marketing of the very word Holocaust: I half expect to see the little 'TM' after it" (1994). For Irving, denial has become a war, which he has described in military language: "I'm presently in a fight for survival. My intention is to survive until five minutes past D-day rather than to go down heroically five minutes before the flag is finally raised. I'm convinced this is a battle we are winning" (1994). After completing his biography of Goebbels, Irving says, his publisher not only backed out of the contract because he had become a Holocaust denier but is trying to retrieve the "six-figure advance." The biography was published by Focal Point, Irving's own publishing house in London.

Irving's attitudes about the Holocaust have evolved, beginning with his 1977 offer to pay $1,000 to anyone who could provide proof that Hider ordered the extermination of the Jews. After reading

The Leuchter Report

(1989), which argues that the gas chambers at Auschwitz were not used to commit homicide, Irving began to deny the Holocaust altogether, not just Hitler's involvement. Curiously, he sometimes wavers on the various points of Holocaust denial. He told me in 1994 that reading Eichmann's memoirs made him "glad I have not adopted the narrow-minded approach that there was no Holocaust" (1994). At the same time, he told me that only 500,000 to 600,000 Jews died as the unfortunate victims of war—the moral equivalent, he claimed, to the bombing of Dresden or Hiroshima. Yet on July 27, 1995, when asked by the host of an Australian radio show how many Jews died at the hands of the Nazis, Irving admitted that perhaps it was as many as four million: "I think like any scientist, I'd have to give you a range of figures and I'd have to say a minimum of one million, which is monstrous, depending on what you mean by killed. If putting people into a concentration camp where they die of barbarity and typhus and epidemics is killing, then I would say the four million figure because, undoubtedly, huge numbers did die in the camps in conditions that were very evident at the end of the war"

(Searchlight

editorial, 1995, p. 2).