Why We Love Serial Killers (33 page)

Read Why We Love Serial Killers Online

Authors: Scott Bonn

Rick Staton, who is a funeral director by profession, said that he became bored with his career and discovered that collecting murderabilia helped him to deal with the “mediocrity of it all.” He said, “My interest in serial killers probably stems from my love of movie monsters during the 1950s when I was a kid.” This seems to be a popular and consistent pattern among serial killer fans. As discussed in chapter 10, serial killers are for adults what movie monsters are for children—scary fun. Staton also contends that his “fascination with death is more normal than abnormal” and he believes that many people “fantasize about violence and murder but will not act on their fantasies, while some people—serial killers—are sick enough to do it.”

Tobias Allen claims that the late John Wayne Gacy ranks first among all serial killers in terms of the number of inquiries he receives from fans and collectors about artifacts. Perhaps due to fate, Staton and Allen were introduced to one another by the “Killer Clown” himself. Staton was already the exclusive dealer of Gacy’s artwork by the time he met Allen. Staton had developed a relationship with Gacy while the killer was painting on death row. Gacy asked Staton to become his exclusive art dealer prior to his execution. Allen confirmed that people from all around the world contact Staton to inquire, “Where can I get an original Gacy painting? How can I get a Gacy?” One avid Gacy collector told Staton that the late serial killer’s artwork is “an important part of history and his choice of colors also match the colors in my home.” The appeal of serial killer artwork is clearly personal and highly subjective.

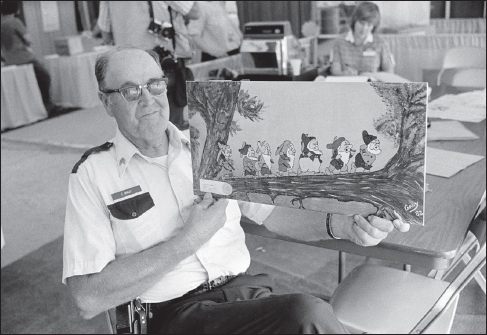

A John Wayne Gacy painting titled “Hi Ho, Hi Ho.” (photo credit: Associated Press)

The dealers of murderabilia emphasized that a prospective seller must first befriend an incarcerated killer and gain his trust before requesting to represent his art or other items for sale. In 2011, Eric Gein told Christina Ng of ABC News:

You can’t write to Richard Ramirez or Charles Manson and say, “Send me some artwork.” It doesn’t work like that. The relationship we have with these infamous serial killers, it takes time. It takes trust. You have to build a friendship, build a relationship just like you would with anyone else.

112

Gein said that once he forges a relationship with a killer, he is forthcoming about the fact that he wants to sell items of merchandise or art from that person. He finds that incarcerated criminals appreciate his candor once a relationship has developed between them. Gein is not the only one to follow these principles. Rick Staton developed a working relationship with serial killer Elmer Wayne Henley in addition to John Wayne Gacy, using the same method. Staton said that he was first attracted to Henley because of the “ghoulish horror” of his crimes. Henley is Houston’s most notorious serial killer of all time. In the early

1970s, Henley and his partner in killing, Dean Corll, carried out the horrific sexual murders of twenty-seven children. In the film

Collectors

Staton said, “Henley’s murders were the most ghastly thing I’d ever heard of and I couldn’t wait to get to know the guy. The brush with deviant celebrity was the big thrill for me.” Now serving multiple life sentences, Henley began to paint at Staton’s behest and the dealer is proud that he got Henley to “take the first step” into creating art.

Opposition to the Murderabilia Trade

Many people consider the sale of serial killer artwork and memorabilia to be tasteless, sensationalistic, exploitative, and obscene. Such people say that it poisons the memory of the victims, and that it is a sign of an American culture in spiritual decline. Commenting on this perspective in the film

Collectors

, Dr. Harold Schechter said:

What people have found so reprehensible about art [and artifacts] produced by serial killers is not the subject matter itself . . . What inspires such widespread disgust is the mere notion that convicted lust killers are allowed to be treated like minor celebrities and enjoy the ego gratification of having their work put on display.

Not surprisingly, the business of selling murder memorabilia has many vocal opponents, particularly among the families of victims. One such person is the brother of a boy who was killed by serial killer Elmer Wayne Henley, whose art is represented by Rick Staton. The victim’s brother, who chooses to remain anonymous, said, “These boys died in agony. This killer up here gets an art show? This is an abortion of justice.” Another family member of a victim who has aggressively spoken out against the murderabilia business is Dee Sumpter of Charlotte, North Carolina, whose daughter Shawna was killed by serial strangler Henry Louis Wallace in 1993. “The way he killed Shawna was a very personal killing,” Sumpter told ABC News’ Charlotte affiliate WSOC-TV. She said, “It was with his hands, he strangled her, and the unmitigated gall of him to sell a photo or an artist rendering of such—I simply don’t have words.” Sketches of Wallace’s hands have been listed for sale online starting at $100 each. Sumpter has admonished the public, saying, “Have a conscience. Have a heart. Have a mind. Legislatively, I know there has to be something that can be done to stop this.”

Perhaps the most vocal opponent and leader of efforts to ban the sale of criminal art and artifacts is Andy Kahan, a victim rights advocate who works for the Houston Police Department. He has spent twenty years working against the sale of “murderabilia,” a term that he coined to define any items that have market value simply because of their connection to a murderer. Kahan told ABC News that the sale of murderabilia is a “wacky, insidious industry.” He said, “I think society has always had a fascination with the morbid and the ones who commit these kinds of crimes” but he finds the collecting of murderabilia to be “pathetic.” Kahan is troubled and incensed by the lack of consideration shown by the buyers and sellers of merchandise for the feelings of victims’ families. Regarding this, Kahan told ABC News, “From a victim’s perspective, nothing is more nauseating and disgusting than finding out that the person who murdered your loved one is hocking items to make a buck. It’s like being gutted all over again by the criminal justice system.”

113

He further noted that the public can easily list the names of celebrity serial killers such as Dahmer, Ramirez, or Bundy but cannot recall a single one of their victims. Kahan is correct in this assessment and it is a sad and ironic truth about the public’s fascination with serial murder.

Andy Kahan, a victim rights advocate and opponent of the “murderabilia” trade, in his Houston office. (photo credit: Associated Press)

Kahan got interested in making sure that serial killers could not profit from their crimes after reading a newspaper article about the late Arthur Shawcross who had sold his original paintings and poems from his prison cell in upstate New York. Prior to his capture, Shawcross had sexually assaulted, raped, killed, and mutilated at least fourteen people, including two children, in the 1970s and 1980s. When Kahan discovered that murder memorabilia was being sold on eBay in 1999, he made it his mission to stop the sales. He told ABC News, “I was just stunned and mortified that individuals can commit these types of offenses and go on to further claim infamy and immortality” through the sale of their artifacts to the public. He eventually convinced eBay to prohibit the selling of the merchandise but the vendors had already tapped into a niche market and discovered that there was great demand for the items, so a handful of entrepreneurs such as Eric Gein built their own websites.

Crafting legislation to curb the murderabilia market has been difficult and mostly unsuccessful. On September 25, 2013, a bill was introduced in Congress for the third time by Senator John Cornyn (R.-Texas) to combat the sale of murderabilia. The law is intended to ban a specific list of criminals from sending anything outside of prison by mail. The outcome of the proposed bill was undetermined at the time of this publication.

Kahan has found out that securing legislation to outlaw the sale of murderabilia is very difficult because the vendors are not doing anything illegal. In the murderabilia business, a third party outside of prison is doing the selling and profiting from the items, which is entirely legal. Moreover, if the murderabilia vendors choose to send money or other gifts to the imprisoned criminals in exchange for their cooperation it is legal, so long as the killers are not profiting directly from the sale of the items. Kahan has twice attempted to file a federal law that would prohibit the selling of murderabilia but has not been able to get a hearing. In 2011, Kahan told Christina Ng of ABC News:

Unfortunately, they [the vendors] are correct. It’s legal. I’m a firm believer in free enterprise and capitalism, but you should not be able to rob, rape and murder and then turn around and make a buck from it. It’s that simplistic. It’s one of the most egregious things I’ve seen after being involved in the criminal justice system for twenty-five years.

114

The Son of Sam Laws

The so-called Son of Sam laws keep convicted felons in many states from profiting from their crimes by selling their crime stories directly to book publishers, film producers, or television networks. According to Kahan, the Son of Sam laws are based on a premise that “when you commit [extremely violent] crimes, you lose certain rights and privileges. One of them is the ability to tell your story.”

115

While one would not normally associate David Berkowitz with the First Amendment right to free speech, legal scholar David L. Hudson, Jr., explained that the serial killer provided a test of the First Amendment when he was offered a large sum of money for his personal story following his criminal conviction. Named after Berkowitz’s serial killer alter ego, the Son of Sam laws are designed to take money earned by convicted criminals from expressive or creative works (e.g., books, films, TV shows, etc.) about their crimes and give it to their victims or the family members of their victims. The following discussion is based on a critique of the Son of Sam laws presented by Hudson, who is a First Amendment expert.

116

The Son of Sam laws were passed as a direct result of the celebrity criminal status attained by serial killer David Berkowitz. In 1977, after hearing reports that Berkowitz was being offered a significant amount of money for the rights to his personal story, the New York State Assembly passed a law requiring that a convicted criminal’s income from creative works describing his or her crimes must be deposited in an escrow account. The funds from the escrow account are then to be used to reimburse crime victims and their families for the harm they have suffered. Supporters of the laws say that they help crime victims and prevent convicted offenders from profiting from their crimes. Opponents counter that the laws infringe on fundamental First Amendment principles and rights.

Following the example established by New York, more than forty states eventually passed Son of Sam laws. In a number of high-profile instances, however, state supreme courts have struck down their Son of Sam statutes for being unconstitutional in that they restrict freedom of speech. For example, the Nevada Supreme Court struck down its Son of Sam law in a constitutional challenge filed by former prison inmate Jimmy Lerner, who wrote the popular memoir

You Got Nothing Coming: Notes from a Prison Fish

. Lerner had served three years in prison for a voluntary manslaughter conviction following the suffocation death of his friend Mark Slavin in a Reno, Nevada, hotel room in 1997. Slavin’s

sister, Donna Seres, filed a lawsuit in August 2002 to collect profits from Lerner’s book. In January 2003, a Nevada trial court judge dismissed Seres’s lawsuit on First Amendment grounds. Lerner’s attorney, Scott Freeman, explained the verdict when he said, “The [Nevada] law is content-based. It is very clear that these laws chill free speech. They not only violate the First Amendment rights of people like Mr. Lerner who engage in expressive work, but people also have a constitutional right to read books like his and receive information.”

117