Will Eisner (39 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

At the 1989 San Diego Comic-Con with comics giants Burne Hogarth, Jerry Robinson, and Jack Kirby. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

According to Ann Eisner, her husband gave a lot of thought to the awards before accepting the offer. “At first he was very wary,” she remembered. “He was always very suspicious of awards. He put down some very, very firm conditions—that they be objective, that he have nothing to do with selections, that it be done by a group, that it not be a favoritism or popularity thing. You could like or dislike the cartoon or the person, but that had nothing to do with it. It had to be based on merit.”

Even with these stipulations, Ann had strong reservations about her husband’s winning such an award, which was entirely likely.

“I felt that if the award was named after Will, he should not be able to participate. I said, ‘You ought to disqualify yourself,’ but he said, ‘I can’t very well …’ Burne Hogarth, who for some reason didn’t like Will, was interviewed, and he said, ‘What do you think about a man who has an award named after himself so he can win it?’ That’s the kind of stuff that people say, even though you know it isn’t true and it’s done completely out of your control. People are always going to say that you had an

in

on that award. I said, ‘Will, it’s just not you. You shouldn’t have people think that about you.’ But he did not listen to me.”

Dave Olbrich bowed out of his administrative post shortly after the awards were introduced, and Jackie Estrada, a volunteer organizer with San Diego Comic-Con, took over. “Dave and Will and Denis Kitchen came to Comic-Con and said, ‘Since you’re nonprofit, would you be willing to take over these awards and have them under your umbrella?’” she recalled. “They suggested that I be the one to administer them.”

Estrada was well qualified for the job. She had attended the very first San Diego Comic-Con back in 1970 and became involved in it as a volunteer four years later. What started out as a part-time seasonal job blossomed into a year-round adventure. She eventually wound up inviting guests and working on the souvenir book, which put her in touch with a large number of artists, including Eisner, who contributed art to the annual souvenir book.

By this point, conventions bore almost no resemblance to Phil Seuling’s old Fourth of July gatherings in New York, and none was bigger than the annual gala event in San Diego, which featured enormous crowds arriving from all over the world, many decked out in the costumes of their favorite characters; panel discussions with some of the biggest names in the industry; and displays and booths selling, advertising, or showing off anything related to comics, from memorabilia to the latest offerings. The convention, with its high energy and noise, was not for the faint of heart. People were packed in so tight that just walking from display to display required resolution and patience. Art and commerce collided, with predictable results.

Having been around since the early days of the conventions, Eisner had watched them grow and evolve from the modest to the overblown, and he observed their effect on the industry. “It is to me a most important development in the history of the comic book marketplace,” he said of the comics convention. “I believe it will be seen by historians as an underlying force that changed the direction of comic book content.”

The Eisner Award ceremonies became one of the cornerstones of the convention in San Diego. In her early days with the awards, Jackie Estrada was given a crash course in the logistics of organizing and administering the industry’s version of the Oscars. Planning began months prior to the awards ceremony, and the schedule was tight.

“We mail out a call for stories,” she said, explaining the process that has evolved over the years, “and tons of books come pouring in. I have five judges, selected to get the full spectrum of background. I have a retailer, somebody from book distribution, someone who actually creates comics, a journalist of some kind, and a reviewer. I bring these five people to San Diego, to a hotel for a three-day weekend, and they have a meeting room where all the submitted material is laid out. They have to narrow everything down to the most worthy items in each category, then make sure they’ve read all those items in every category, and then vote on them to determine what goes on the ballot. The ballot goes out to creators, publishers, and retailers in the comic book industry. There’s an online ballot today. To be nominated is to draw attention to the best material being done in comics, so we try to publicize that as much as possible. Then we start to prepare for the big ceremony in San Diego. All of the nominated items have to be scanned to Photoshop and set up for PowerPoint. Then I work with an MC for the awards. We line up celebrity presenters. We have to set up the whole event itself, with VIP seating and dealing with hotels, food, and publicity.”

Will Eisner himself presented the awards to each of the winners, and for many of them, the handshake from the comics legend was as big an honor as winning the award itself. Eisner enjoyed the attention, but even for someone half his age, standing onstage in one place for a couple of hours could be physically difficult. Eisner soldiered through the ceremonies, refusing to be seated, until one year he faced a situation that was in parts a tribute, a practical joke, and a means of getting him off his feet. The idea originated with comics artists Jeff Smith and Kurt Busiek, who were concerned about having Eisner stand throughout the ceremony. They contacted Jackie Estrada and outlined their plan.

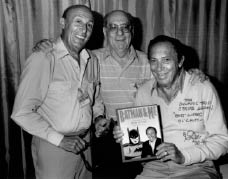

With DC editor Julius Schwartz and

Batman

creator and high school friend Bob Kane. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

“We’ve got to get some kind of throne,” they said.

One of the convention workers had connections with the San Diego Opera, and it was through the opera company that Estrada was able to borrow a throne upholstered in red velvet. The prop, everyone involved agreed, was perfect. Smith and Busiek hid the throne behind a curtain until after Eisner had been introduced and was onstage, and then they brought it out, to the laughter and applause of the awards ceremony attendees. Eisner, though slightly embarrassed, played along, taking a seat and posing for pictures until the hoopla had died down. Then he stood up—and stayed that way for the remainder of the ceremony.

J. Michael Straczynski, winner of an Eisner Award for Best Serialized Story for his work on

Amazing Spider-Man

in 2002, probably offered the best summation of the experience of receiving the award from Eisner when, after taking it and shaking Eisner’s hand, he held the award up in the air and said, “You know, you get the Emmy, you don’t get it from Emmy. You win the Oscar, you don’t get it from Oscar. How freakin’ cool is this?”

While organizing his office and files after his move to Florida, Eisner came across a small book’s worth of artwork originally intended for

New York: The Big City

. The pieces, like those in

The Big City

, were short takes—graphic essays, he called them—that hadn’t fit into the other book’s thematic structure, but the art was too good to be discarded. In looking over the work, Eisner decided to gather the pieces into three basic themes—Time, Space, and Smell—and release them as a small book.

Eisner never intended

City People Notebook

to measure up as a literary work against his ambitious graphic novels or even to

New York: The Big City

. It was more of a confection, a grouping of thirty-two pieces, some only a page or two in length, all dealing, like the vignettes in

The Big City

, with what Eisner called “the most influential and pervasive environmental phenomena” found in the daily life of New York City. The pieces, Eisner said, were very personal—the kinds of sketches he might have slipped into other graphic novels—and he included self-portraits in some of the art, depicting the artist as an observer.

Eisner’s decision to release the sketchy, disparate pieces was based largely on a writer’s ultimate nightmare: he was suffering through a prolonged period of writer’s block and couldn’t come up with a topic for a full-length graphic novel. Work on

The Dreamer

and

The Building

had drained him, and as he complained in a letter to Dave Schreiner, he was struggling to find the enthusiasm that fueled each new project.

“While it is true that I go through periods of ‘blockage’—generally after the completion of a work—it usually lasts only until I get ‘revved’ up for a new project,” he wrote. “What I did reveal to Denis was my feeling of dissatisfaction with the lack of real challenge among the stored up notes for new projects that fill my desk-top file next to the drawing board. I told him I was always in search of new departure and finding them these days was hard work. At any rate finding them these days was not as easy as heretofore. And adding to the agony was the fact that working behind or with a writer (as Denis suggested) does not solve my frustration a bit. It is very exhilarating being a pioneer but it loses some of its euphoria when the time comes to move on and find another mountain to conquer.”

The mountain he was talking about was just up ahead. Conquering it would involve one of the biggest struggles of his career.

chapter fifteen

T H E H E A R T O F T H E M A T T E R

I think many of us in this business are Don Quixotes. Anybody in the business of innovation is in pursuit of something that nobody else believes exists.

I

n the spring of 1989, Eisner began work on his lengthiest graphic novel since

A Life Force

. This new book, eventually published as

To the Heart of the Storm

, was designed to focus on the insidious forces of anti-Semitism in the Depression-era New York of Eisner’s youth. It was to be a work of fiction, but after numerous reworkings, it would become the most autobiographical work Eisner would ever create.

Earlier books had addressed compelling personal issues in his life, but aside from

The Dreamer

and “Cookalein,” his autobiographical coming-of-age short story in

A Contract with God

, Eisner consciously avoided depicting actual events from his private life in his work. Whether this choice was a matter of dignity or courage is a subject for debate. According to Eisner, he had changed the names in

The Dreamer

to avoid embarrassing living people depicted in the book, but as he would admit in interviews after the publication of

To the Heart of the Storm

, he found “standing naked in the drill field,” his description of the self-reflection required for the process of autobiographical writing, exceedingly difficult.

“When I was younger, I couldn’t bring myself to do it,” he confessed. “I didn’t dare bare those details of my life. I think autobiographies are done mostly by older people because they have reached the point where they don’t have much to lose.”

In writing about the Depression and the uneasy period leading up to World War II, Eisner almost inevitably included incidents from his own life. After all, he had lived through the period, and he adhered to the old axiom that a writer should write about what he or she knows. As a young boy, he’d coped with anti-Semitism in his own neighborhood, and his brother, Julian, had permanently lost a precious part of his identity because of a flashpoint moment on the street and the resulting name change. Sam Eisner’s story, from his days in Vienna to his eventual move to the Bronx, exemplified the European Jewish immigrant experience and the hardships of adjusting to life in America. And to illustrate the way Jews were socially shunned, Eisner needed only to deliver a heartbreaking story from his own youth, when a girl whom he fancied, not knowing that he was Jewish, invited him to a party, only to learn the truth from one of Eisner’s rivals and panic about how her parents would react to her bringing a Jewish boy into their home. The book, Eisner decided, would achieve its greatest impact as a straight-on memoir rather than a fictionalized account.

Still, for a man accustomed to controlling the flow of public information about his private life, Eisner found writing about his family especially problematic. Even though both of his parents had died years earlier, Eisner agonized over how to portray them in his book. He didn’t trust the accuracy of his memory, and he knew that if he was as truthful as his memory permitted, his parents—or at the very least his mother—would not be seen as sympathetic characters.

“To write about your parents and their lives is very painful,” he said, likening the process to the catharsis of psychotherapy. “You have to fight the feeling of betrayal if you want to tell something honestly, like the relationship between my mother and father. This was something that I always held very private. I wouldn’t tell that to anybody before, and now I’m about to tell it to the world. I ask myself, if my mother and father were alive, would they not feel betrayed by that; am I telling the truth?”

And what, he wondered,

was

the truth? As he pointed out in an interview with journalist Shawna Ervin-Gore, his relationship with his mother and father had changed significantly over the years. He’d gone through periods when he was very angry with them and saw them in a negative light, only to soften in later years when his own experiences added texture and color to what had at one time seemed very black and white. Furthermore, Sam and Fannie were remembered in different ways by each of their children, as Eisner discovered after the publication of

To the Heart of the Storm

. “When I showed the finished book to my brother,” Eisner recalled, “he said to me, ‘I don’t remember Mom and Dad like that.’ And when I showed it to my sister, who is thirteen years younger than I am, she said she remembered them the way I did.”

To get around some of these concerns, Eisner decided to narrate the story of his youth through a series of extended flashbacks. He opened

To the Heart of the Storm

with Willie, his protagonist, sitting on a train in his army uniform, talking with two other draftees on their way to basic training. One of his two fellow inductees is the Catholic editor of a Turkish-American newspaper in Brooklyn, the other a redneck southerner whose coarse opinions immediately send Willie into meditations about his childhood and the bigotry he’d seen. As a literary device, the flashbacks work effectively: Willie’s memories are selective, reliable but not necessarily complete. These impressions, the diamond-hard truths of what remained with him over the years, are what matter most.

To the Heart of the Storm

was a masterwork, comparable to, or even surpassing, the excellence of

A Contract with God

or

A Life Force

. But as Eisner’s correspondence with Dave Schreiner indicates, the writing did not come easily. Schreiner, by now totally frank with Eisner about his work, was immediately impressed with the rough dummy of the book, but he had serious issues with it as well.

“I think it’s your most powerful work to date,” he wrote to Eisner in July 1989, “and if it were published as is, it would probably be all right. I see no need for you to feel apprehensive about it. It

is

intense, and rightfully so. It is your perspective on your early life, and in a novel, you get to call ’em as you see ’em.”

Schreiner went on to offer detailed criticism of what he perceived to be the technical and editorial flaws of the book. He had serious reservations with the balance of the book’s characters, who, he felt, “on the whole … [were] either Jewish or anti-Semitic.” It would work better, he suggested, if the characters were further fleshed out. “It would perhaps be a bit more authentic if you could humanize these characters a little more. Add a little grey, perhaps, to the black and white. In a good novel, the reader is given a hopefully complete picture of a human being, good and bad, and draws an overall judgment of that character from the picture drawn in the book.”

One of Schreiner’s strongest objections was to Eisner’s working title:

A Journey to a Far-Off Thunder

. The title, he told Eisner, fit the book, but it wasn’t the best from a marketing standpoint. “Would you consider thinking of a

short

and

punchy

main title, and using the

Journey

line as a subtitle?”

Eisner considered Schreiner’s suggestions, made some revisions, especially on the characters, and submitted a new draft to Schreiner. While conceding that the characters in the new version were more nuanced than in the previous version, Schreiner still wasn’t satisfied. “Ambiguity and ambivalence—this is what can make good books,” he wrote, exhorting Eisner to take it even further. In addition, he gently prodded Eisner toward using his mother’s real name rather than “Birdie,” as he was calling Fannie in the draft. He appreciated the power Eisner’s autobiographical segments about his parents already had, but he believed they could be revised to be even more effective. The biggest technical problem, in Schreiner’s view, involved the flashbacks: as written, they could be confusing, especially because there were sometimes flashbacks within the flashbacks; he encouraged Eisner to clean them up. He still didn’t like the title, although (perhaps because he knew he could push Eisner only so far) he mentioned it only in passing.

And so it went, for more than a year. Eisner revised, and Schreiner pushed for more. Finally, Eisner was reaching the end of his patience. On September 4, 1990, he sent what he considered to be the final draft, with a terse note: “Enclosed: it’s

The Book

!!! Note I’ve settled on a shorter title ‘To the Far Off Thunder’—based on your advice. Hope you can work on this before your wedding—I really cannot expect you to take this book on your honeymoon.”

Pending nuptials didn’t prohibit Schreiner from reading and responding. After the difficulties he and Denis Kitchen had experienced with Eisner over the lengthening of

The Dreamer

, Schreiner recognized, in the stubborn tone of Eisner’s letters and telephone calls, that Eisner felt he had reached his limit. Schreiner was very fond of the book, but he still felt compelled to toss out a few final suggestions that he hoped would strengthen it. Most were of the technical variety: the newspaper headlines that Eisner used were often incorrect. In one panel, for instance, Eisner had a headline with the Nazis invading Belgium in 1942. “In 1942,” Schreiner informed Eisner, “that battle was over for two years. I suggest … NAZIS ADVANCE IN NORTH AFRICA.”

This was small but important stuff, as were the misspellings and typos. But Schreiner still had big problems with Eisner’s title, and he now made one last ditch effort to convince him to change it.

“My major misgiving is the title,” he stated. “I still don’t like it. It just doesn’t reach out and grab me. Are you open to suggestions for change, if we can find a suitable one? Please say you are: by far and away, the weakest part of this book is its title … It would be a dirty shame if people were not drawn to this book because of its weak title.

“This is your strongest work to date, Will,” he continued. “I know you seem to care more for the writing than the art, and ordinarily I do, too. I don’t even feel competent usually to comment on art. But I know good art when I see it, and I can’t let this opportunity pass without saying that I see it here … I think you’ve done a particularly masterful job this time.”

To Schreiner and Denis Kitchen’s great relief, Eisner relented and retitled the book

To the Heart of the Storm

, putting an end to one of the longest-running disagreements he’d ever had with his editor and publisher. The work on this book signaled Schreiner’s finest hour as Eisner’s editor, and Eisner seemed to recognize it. “My gratitude to Dave Schreiner, who edited this book and persevered with me through the painful revisions,” he wrote in the book’s acknowledgments. “His judgment is unfailingly dependable.”

The reviews ran the spectrum from lukewarm to breathless. In one that probably made Eisner wince,

Publishers Weekly

praised Eisner’s story but objected to what the reviewer dismissed as “schmaltzy” and “melodramatic” graphics, calling the book “a vivid but flawed work from an acknowledged master of the comics medium.”

Don Thompson was much more generous in his review in

Comics Buyer’s Guide

, one of the industry’s most influential publications. “This is an outstanding work even by Will Eisner’s standards,” Thompson wrote. “Don’t miss this. Keep a copy handy for any

truly

intelligent friend who asks you why you are still reading comic books at your age. If this doesn’t answer him/her, maybe he/she is less intelligent than you thought.”

Eisner was often asked where he came up with the ideas for his graphic novels and how he chose his projects. He’d reply that some were from scenes he had witnessed; some came from thinly disguised but deeply personal autobiographical material he’d carried around in his head for decades, waiting for the proper moment and inspiration to motivate him to work it into a story. He’d overhear bits of conversation, see a compelling news item on television, or maybe find something worthwhile in the newspaper. He kept an idea file of notes, clippings, and rough pencil drawings, every scrap representing a seed for a story. His emotions played a heavy role in his decisions about what projects to pursue.

Such was the case in early 1991, when he read a newspaper account about a woman named Carolyn Lamboly, a disabled, destitute woman who, in the throes of loneliness and depression, had hanged herself with a light cord a few days before Christmas 1990. Her body lay for two months in a funeral home, and when no one stepped forward to claim her, she was buried in an unmarked grave in Dade County’s Memorial Park. As sad as the story was, it got worse. The woman had spent a year trying to get help from government and community services, but she had become lost in the system, just another name on an endless list of faceless, “invisible” people you see every day but never notice. On January 3, 1991, just days after her suicide, she was formally approved for housing and medical coverage.

Angered by the story, Eisner set out to work on three comic book–length stories about people who, like Carolyn Lamboly, went about their lives unnoticed. Published by Kitchen Sink Press as three individual comic books, the stories, entitled “Sanctum,” “The Power,” and “Mortal Combat,” were eventually bundled into a single book and published as

Invisible People

.

“Sanctum,” the story most closely modeled after Lamboly, is a tale about Pincus Pleatnik, a bland, middle-aged bachelor who works as a clothes presser, keeps to himself, and tries to blend into the scenery, believing that anonymity “is a major skill in the art of urban survival.” His life takes an irreversible turn one day when he opens the newspaper and sees his name listed on the obituaries page. He suddenly has to prove—to his boss, his landlord, the newspaperwoman reporting his death, and the police—that he’s alive. It doesn’t go well. After a series of misadventures bordering on the absurd, he winds up homeless and jobless and ultimately loses his life as a result of his quest to prove that he’s not dead. In a bitter postscript to the story, the person who wrote his obituary, now retiring and being honored at a party thrown by her employer, receives an award and a $5,000 savings bond for the accuracy of her reporting.