Will Eisner (42 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Spirit

bookplate, distributed in Europe, but unpublished in the United States. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

Minor Miracles

, Eisner’s first new book with DC, veered sharply away from

A Family Matter

, as if Eisner needed to cleanse his mind after the psychological brutality of his last graphic novel for Kitchen Sink. In

Minor Miracles

, Eisner returned to Dropsie Avenue, where anything was possible in the drudgery of everyday life. A wealthy merchant just might pass by a down-and-out cousin digging through the trash and offer to stake him the money needed to start a business and turn his life around. A quick-thinking kid might come up with an ingenious plan to avoid a beating at the hands of neighborhood bullies. A new kid of mysterious origins might appear out of nowhere and touch off a series of good fortune to everyone in the neighborhood. A crippled young man might meet and marry a young woman who, as the result of childhood trauma, is unable to hear or speak, and, with any luck, live happily ever after with her. The four stories in

Minor Miracles

sprang from these possibilities, and under Eisner’s writing and drawing, they became shards of magic glistening in the otherwise drab city streets. Ordinary occurrences had extraordinary consequences, becoming little miracles that no one seemed to notice.

“The stories in this work resemble the stories my parents referred to as ‘meinsas,’” Eisner wrote.

And while they are apocryphal, they were nevertheless distilled from my remembrance of those that were the common property of our family. For example, my mother would point to an old man feeding pigeons in the park and tell me, ‘That is an uncle on your father’s side … let me tell you about him … it’s a miracle.’”

DC Comics soon learned what Denis Kitchen had known at Kitchen Sink Press: Will Eisner was so prolific that it was impossible to publish his books as quickly as he was writing them. He had a backlog of material that he wanted to publish, including a new collection of graphic stories based on what he observed during his travels for

P

*

S

magazine. He’d worked on the book during the last days of Kitchen Sink Press, even though he didn’t have a market for it, but when he insisted that this new book be published in time for the upcoming San Diego Comic-Con, DC, unenthusiastic about the book to begin with, declined, stating they couldn’t meet Eisner’s publishing timetable.

The book,

Last Day in Vietnam

, landed with Dark Horse Comics, an Oregon-based company founded in 1986 and specializing in graphic novels and comic books for mature readers as well as in serious studies of their creators and comics history.

Diana Schutz, an editor at Dark Horse, was assigned the task of preparing

Last Day in Vietnam

under the tightest production schedule imaginable. The book landed on her desk in April, and with the San Diego convention looming only three months in the future, she had to accomplish the copyediting, design, story sequence, and photo work in one-third the production time to which she was accustomed. She’d never worked with Eisner before, and had no idea what to expect. On the business end, she had to solicit advance orders in a time-crunch that, by comics standards, was preposterous.

“Those orders guide your print numbers,” she explained. “It was April, and we were already soliciting for July. To solicit without any part of a book to send is crazy, impossible. But those were my marching orders.

“Will had already worked with Dave Schreiner on the various stories in the book. All the stories were done and the pages were drawn. The book was finished. That’s why Will wanted it out for San Diego. In his mind, all we really needed to do was publish the damn thing, and, in a sense, that was true. Will was perfectly amenable all the way through, never once was there any kind of tussling or arguing.”

Eisner believed that

Last Day in Vietnam

, with only limited use of dialogue balloons, marked a new approach that comics could take in the future. In these stories, the character is speaking directly to the reader, making the reader a participant in the story.

“It’s an innovation which I thought has been coming for some time,” Eisner explained in an interview that appeared when

Last Day in Vietnam

was published in 2000. “Anybody who has followed my work will probably know that I make a very major effort to make contact with the reader—almost directly. That’s one of the reasons I use rain and weather and so forth in many of my stories—it seems like it involves the reader more heavily, brings them more into the story being told.”

Eisner had attempted this type of narrative on one previous occasion, in a

Spirit

story in which a character, a sea captain, spoke directly to the reader. Eisner liked the approach, but he never followed up on it, partially because his frenetic work schedule prohibited his experimenting further and partially because this type of storytelling could be used only in very specific kinds of stories. “It only works on material where all the dialogue comes from one person,” he pointed out. “I don’t know how you could eliminate the use of balloons in other situations.”

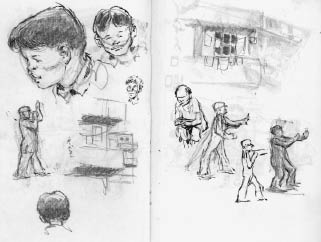

The artwork for the stories was similarly inventive. During his visits to Korea and Vietnam, Eisner had drawn numerous sketches of what he saw. With this new book, he wanted his readers to feel as if they were looking through his sketchbook, seeing what he saw, reacting to events the way he had reacted to them decades earlier.

“I wanted to keep it as close to a kind of diary as I could,” he said of the approach. “As a matter of fact, originally I thought it might work to emulate a loose leaf binding on the inside, with lined paper, but I decided it was just too much, it was too gross. But the reason for this pencil technique was to create a very rugged, rough sketchbook look, almost.”

The art has a grainy, gritty look, as if the pictures had been hastily penciled into a notebook by someone in the field. To further achieve the effect of authenticity, Eisner included archival photographs from Vietnam between stories.

Eisner carried a sketchbook whenever he traveled, creating studies of people, buildings, and places. These previously unpublished sketches are from a notebook Eisner kept while visiting China. (© Will Eisner Studios, Inc., courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

The six stories in the volume were nonfiction “memories,” as Eisner labeled them on the book’s cover, based on events that Eisner witnessed in person. Only one—the title story—takes place amid actual fighting, but even so, they are heartbreaking, frightening, uplifting, ironic, and violent, with the kind of tension, drama, and boredom that GIs felt when they were safe on a base or on leave, knowing that combat was up ahead. One story, presented with no dialogue or narrative, offered one of the most violent scenes in the book, when a young soldier is seriously injured by a prostitute. Fear rumbles just beneath the GIs’ tough talk, and Eisner makes it very clear that the most dangerous soldiers are the ones itching for battle—the ones who will kill or be killed, contributing to statistics. Senseless death is at the core of the two stories eliciting the greatest emotional response from Eisner—and, presumably, the reader. In “A Dull Day in Korea,” the only story set outside Vietnam, a loudmouth GI, bragging about his hunting abilities back home in West Virginia, decides to display his marksmanship by shooting an innocent woman out gathering wood, only to be stopped by his commanding officer before he can kill her. “A Purple Heart for George” tells the story of a gay GI named George, who gets drunk every weekend and writes a note requesting dangerous combat duty; the weekly notes are intercepted and destroyed by friends working in the base commander’s office, until finally—and tragically—George gets his wish when no one is in the office to tear up his note.

“ ‘A Purple Heart for George,’” Eisner wrote in the book’s introduction, “left a residue of guilt in many of us. I don’t know about the primary actors in that event, which I witnessed, but for me it has never left my mind. I simply cannot forget it.”

Dark Horse published four other Eisner titles—

Shop Talk

,

Eisner/Miller

, a reprinting of

Hawks of the Sea

, and a coffee table book called

Will Eisner Sketchbook

—during Eisner’s brief but productive association with the company.

Shop Talk

, a gathering of the interviews that Eisner published in

The Spirit Magazine

and

Will Eisner’s Quarterly

, featured in-depth conversations with such comics icons as Milton Caniff, C. C. Beck, Jack Kirby, Harvey Kurtzman, Gil Kane, Joe Simon, and Joe Kubert, speaking in an informal setting and talking about their work habits and contributions to comics. All had known Eisner for a long time prior to the conversations and felt comfortable about providing the kind of anecdotal detail that made the interviews a delight to read.

Eisner/Miller

offered a different kind of interview. As originally planned, the book was to be the first of a series of book-length interviews with a younger generation of comic book and graphic novel creators, with such giants in the field as Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, and maybe, with luck, the usually reclusive R. Crumb. But Eisner lived to see only one to fruition.

Eisner/Miller

, as published, was an informative, occasionally contentious discussion between two of the industry’s heavyweights, but getting to that point was more work than anyone had anticipated in 2000, when the book was planned. Miller was busy on a

Dark Knight

project and unavailable, and Eisner was impatient, unhappy about the delays. When the two finally got together in Florida in May 2002, the early going was awkward and, at times, nasty. Eisner hadn’t bothered to read Miller’s latest

Sin City

book, yet he didn’t shy away from critiquing it. Miller, unhappy with Eisner’s condescending posture, grew justifiably defensive. Interviewer Charles Brownstein became a referee trying to keep the conversation on track. During one of the breaks in the conversation, when Eisner had gone into his house, Ann Eisner approached Brownstein and asked what exactly he wanted from her husband. As Brownstein remembered, she then went into the house and talked to her husband. When he returned, Eisner was much more relaxed.

“It didn’t go as smoothly as we would have expected,” Dark Horse founder and publisher Mike Richardson said of the interview sessions. “I think that both went in respecting each other, but when you have two people with egos and differing opinions about what they do, there might be a little bit of friction during the course of something like that.”

When retracing the weekend’s conversations, Miller shrugged off the tension as nothing outside of the ordinary whenever he and Eisner got together.

“It was mild compared to what we’d do privately,” he said. “There are probably people who thought we didn’t like each other, when in fact we loved each other. When I was working on the movie of

The Spirit

, I designed Commissioner Dolan after Will, and his conversations with the Spirit after the conversations that Will and I had. Very frequently, a conversation between Will and me would end with him saying, ‘I don’t know why I even talk to you anymore.’ I used that line pretty much every time Dolan and the Spirit talked.”

Both men enjoyed a good verbal tussle over comics and where they were headed, and while they did loosen up considerably during their discussions for

Eisner/Miller

, they still sparred as often as they agreed, making for an eye-opening, entertaining exchange. The finished book, lavishly illustrated with art from both and presented in a straight Q&A format, was published in 2005, just months after Eisner had passed away. It would stand as his ultimate “Shop Talk.”

Eisner wasn’t yet ready to abandon his obsession with family. He knew that in Ann’s family, he had enough material for a graphic novel that would be a kind of combination of the family saga presented in

To the Heart of the Storm

and the close-up family drama depicted in

Family Matter

. Ann’s family had a long, colorful history, bathed in the wealth acquired from banking and Wall Street, and Eisner was intrigued by the possibilities of exploring the dynamics of a family so unlike his own. He’d grown up in a world of tenements and survival; Ann’s relatives and immediate family were more concerned with social position.