William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (274 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

3.79Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ANTONIO

Which I will do with confirmed countenance.

BENEDICK

Friar, I must entreat your pains, I think.

FRIAR To do what, signor?

BENEDICK

To bind me or undo me, one of them.

Signor Leonato, truth it is, good signor,

Your niece regards me with an eye of favour.

Signor Leonato, truth it is, good signor,

Your niece regards me with an eye of favour.

LEONATO

That eye my daughter lent her, ’tis most true.

BENEDICK

And I do with an eye of love requite her.

LEONATO

The sight whereof I think you had from me,

From Claudio and the Prince. But what’s your will?

From Claudio and the Prince. But what’s your will?

BENEDICK

Your answer, sir, is enigmatical.

But for my will, my will is your good will

May stand with ours this day to be conjoined

In the state of honourable marriage,

In which, good Friar, I shall desire your help.

But for my will, my will is your good will

May stand with ours this day to be conjoined

In the state of honourable marriage,

In which, good Friar, I shall desire your help.

LEONATO

My heart is with your liking.

FRIAR And my help.

Here comes the Prince and Claudio.

Enter Don Pedro and Claudio with attendants

DON PEDRO

Good morrow to this fair assembly.

LEONATO

Good morrow, Prince. Good morrow, Claudio.

We here attend you. Are you yet determined

Today to marry with my brother’s daughter?

We here attend you. Are you yet determined

Today to marry with my brother’s daughter?

CLAUDIO

I’ll hold my mind, were she an Ethiope.

LEONATO

Call her forth, brother, here’s the Friar ready.

Exit Antonio

DON PEDRO

Good morrow, Benedick. Why, what’s the matter

That you have such a February face,

So full of frost, of storm and cloudiness?

That you have such a February face,

So full of frost, of storm and cloudiness?

CLAUDIO

I think he thinks upon the savage bull.

Tush, fear not, man, we’ll tip thy horns with gold,

And all Europa shall rejoice at thee

As once Europa did at lusty Jove

When he would play the noble beast in love.

Tush, fear not, man, we’ll tip thy horns with gold,

And all Europa shall rejoice at thee

As once Europa did at lusty Jove

When he would play the noble beast in love.

BENEDICK

Bull Jove, sir, had an amiable low,

And some such strange bull leapt your father’s cow

And got a calf in that same noble feat

Much like to you, for you have just his bleat.

And some such strange bull leapt your father’s cow

And got a calf in that same noble feat

Much like to you, for you have just his bleat.

Enter Antonio with Hero, Beatrice, Margaret, and Ursula, masked

CLAUDIO

For this I owe you. Here comes other reck’nings.

Which is the lady I must seize upon?

Which is the lady I must seize upon?

⌈ANTONIO⌉

This same is she, and I do give you her.

CLAUDIO

Why then, she’s mine. Sweet, let me see your face. 55

LEONATO

No, that you shall not till you take her hand

Before this Friar and swear to marry her.

Before this Friar and swear to marry her.

CLAUDIO (

to Hero

)

to Hero

)

Give me your hand before this holy friar.

I am your husband if you like of me.

I am your husband if you like of me.

HERO (

unmasking

)

unmasking

)

And when I lived I was your other wife;

And when you loved, you were my other husband.

And when you loved, you were my other husband.

CLAUDIO

Another Hero!

HERO Nothing certainer.

One Hero died defiled, but I do live,

And surely as I live, I am a maid.

And surely as I live, I am a maid.

DON PEDRO

The former Hero, Hero that is dead!

LEONATO

She died, my lord, but whiles her slander lived.

FRIAR

All this amazement can I qualify

When after that the holy rites are ended

I’ll tell you largely of fair Hero’s death.

Meantime, let wonder seem familiar,

And to the chapel let us presently.

When after that the holy rites are ended

I’ll tell you largely of fair Hero’s death.

Meantime, let wonder seem familiar,

And to the chapel let us presently.

BENEDICK

Soft and fair, Friar, which is Beatrice?

BEATRICE (

unmasking

)

unmasking

)

I answer to that name, what is your will?

BENEDICK

Do not you love me?

BEATRICE Why no, no more than reason.

BENEDICK

Why then, your uncle and the Prince and Claudio

Have been deceived. They swore you did.

Have been deceived. They swore you did.

BEATRICE

Do not you love me?

BENEDICK Troth no, no more than reason.

BEATRICE

Why then, my cousin, Margaret, and Ursula

Are much deceived, for they did swear you did.

Are much deceived, for they did swear you did.

BENEDICK

They swore that you were almost sick for me.

BEATRICE

They swore that you were wellnigh dead for me.

BENEDICK

’Tis no such matter. Then you do not love me?

BEATRICE

No, truly, but in friendly recompense.

LEONATO

Come, cousin, I am sure you love the gentleman.

CLAUDIO

And I’ll be sworn upon’t that he loves her,

For here’s a paper written in his hand,

A halting sonnet of his own pure brain,

Fashioned to Beatrice.

For here’s a paper written in his hand,

A halting sonnet of his own pure brain,

Fashioned to Beatrice.

HERO And here’s another,

Writ in my cousin’s hand, stol’n from her pocket,

Containing her affection unto Benedick.

Containing her affection unto Benedick.

BENEDICK A miracle! Here’s our own hands against our hearts. Come, I will have thee, but by this light, I take thee for pity.

BEATRICE I would not deny you, but by this good day, I yield upon great persuasion, and partly to save your life, for I was told you were in a consumption.

BENEDICK (

kissing her

) Peace, I will stop your mouth.

kissing her

) Peace, I will stop your mouth.

DON PEDRO

How dost thou, Benedick the married man?

BENEDICK I’ll tell thee what, Prince: a college of wit-crackers cannot flout me out of my humour. Dost thou think I care for a satire or an epigram? No, if a man will be beaten with brains, a shall wear nothing handsome about him. In brief, since I do purpose to marry, I will think nothing to any purpose that the world can say against it, and therefore never flout at me for what I have said against it. For man is a giddy thing, and this is my conclusion. For thy part, Claudio, I did think to have beaten thee, but in that thou art like to be my kinsman, live unbruised, and love my cousin.

CLAUDIO I had well hoped thou wouldst have denied Beatrice, that I might have cudgelled thee out of thy single life to make thee a double dealer, which out of question thou wilt be, if my cousin do not look exceeding narrowly to thee.

BENEDICK Come, come, we are friends, let’s have a dance ere we are married, that we may lighten our own hearts and our wives’ heels.

LEONATO We’ll have dancing afterward.

BENEDICK First, of my word. Therefore play, music. (

To Don Pedro

) Prince, thou art sad, get thee a wife, get thee a wife. There is no staff more reverend than one tipped with horn.

To Don Pedro

) Prince, thou art sad, get thee a wife, get thee a wife. There is no staff more reverend than one tipped with horn.

Enter Messenger

MESSENGER

My lord, your brother John is ta’en in flight,

And brought with armed men back to Messina.

And brought with armed men back to Messina.

BENEDICK Think not on him till tomorrow, I’ll devise thee brave punishments for him. Strike up, pipers.

Dance, and exeunt

HENRY V

THE Chorus to Act 5 of

Henry V

contains an uncharacteristic, direct topical reference:

Henry V

contains an uncharacteristic, direct topical reference:

Were now the General of our gracious Empress—

As in good time he may—from Ireland coming,

Bringing rebellion broached on his sword,

How many would the peaceful city quit

To welcome him!

‘The General’ must be the Earl of Essex, whose ‘Empress’—Queen Elizabeth—had sent him on an Irish campaign on 27 March 1599; he returned, disgraced, on 28 September. Plans for his campaign had been known at least since the previous November; the idea that he might return in triumph would have been meaningless after September 1599, and it seems likely that Shakespeare completed his play during 1599, probably in the spring. It appeared in print, in a short and debased text, in (probably) August 1600, when it was said to have ‘been sundry times played by the Right Honourable the Lord Chamberlain his servants’. Although this text (which omits the Choruses) seems to have been put together from memory by actors playing in an abbreviated adaptation, the Shakespearian text behind it appears to have been in a later state than the generally superior text printed from Shakespeare’s own papers in the 1623 Folio. Our edition draws on the 1600 quarto in the attempt to represent the play as acted by Shakespeare’s company. The principal difference is the reversion to historical authenticity in the substitution at Agincourt of the Duke of Bourbon for the Dauphin.

As in the two plays about Henry IV, Shakespeare is indebted to

The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth

(printed 1598). Other Elizabethan plays about Henry V, now lost, may have influenced him; he certainly used the chronicle histories of Edward Hall (1542) and Holinshed (1577, revised and enlarged in 1587).

The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth

(printed 1598). Other Elizabethan plays about Henry V, now lost, may have influenced him; he certainly used the chronicle histories of Edward Hall (1542) and Holinshed (1577, revised and enlarged in 1587).

From the ‘civil broils’ of the earlier history plays, Shakespeare turns to portray a country united in war against France. Each act is prefaced by a Chorus, speaking some of the play’s finest poetry, and giving it an epic quality. Henry V, ‘star of England’, is Shakespeare’s most heroic warrior king, but (like his predecessors) has an introspective side, and is aware of the crime by which his father came to the throne. We are reminded of his ‘wilder days’, and see that the transition from ‘madcap prince’ to the ‘mirror of all Christian kings’ involves loss: although the epilogue to

2 Henry IV

had suggested that Sir John would reappear, he is only, though poignantly, an off-stage presence. Yet Shakespeare’s infusion of comic form into historical narrative reaches its natural conclusion in this play. Sir John’s cronies, Pistol, Bardolph, Nim, and Mistress Quickly, reappear to provide a counterpart to the heroic action, and Shakespeare invents comic episodes involving an Englishman (Gower), a Welshman (Fluellen), an Irishman (MacMorris), and a Scot (Jamy). The play also has romance elements, in the almost incredible extent of the English victory over the French and in the disguised Henry’s comradely mingling with his soldiers, as well as in his courtship of the French princess. The play’s romantic and heroic aspects have made it popular especially in times of war and have aroused accusations of jingoism, but the horrors of war are vividly depicted, and the Chorus’s closing speech reminds us that Henry died young, and that his son’s protector ‘lost France and made his England bleed’.

2 Henry IV

had suggested that Sir John would reappear, he is only, though poignantly, an off-stage presence. Yet Shakespeare’s infusion of comic form into historical narrative reaches its natural conclusion in this play. Sir John’s cronies, Pistol, Bardolph, Nim, and Mistress Quickly, reappear to provide a counterpart to the heroic action, and Shakespeare invents comic episodes involving an Englishman (Gower), a Welshman (Fluellen), an Irishman (MacMorris), and a Scot (Jamy). The play also has romance elements, in the almost incredible extent of the English victory over the French and in the disguised Henry’s comradely mingling with his soldiers, as well as in his courtship of the French princess. The play’s romantic and heroic aspects have made it popular especially in times of war and have aroused accusations of jingoism, but the horrors of war are vividly depicted, and the Chorus’s closing speech reminds us that Henry died young, and that his son’s protector ‘lost France and made his England bleed’.

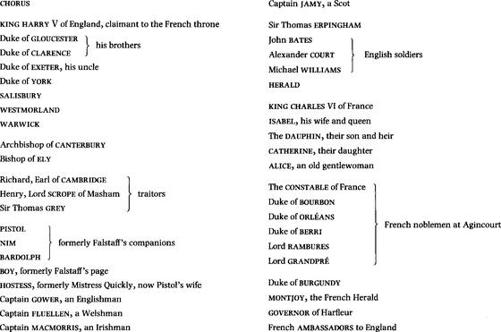

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

Prologue

Enter Chorus as Prologue

CHORUS

Enter Chorus as Prologue

CHORUS

O for a muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention:

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act,

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene.

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

Leashed in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire

Crouch for employment. But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraisèd spirits that hath dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object. Can this cock-pit hold

The vasty fields of France? Or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O pardon: since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million,

And let us, ciphers to this great account,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high uprearèd and abutting fronts

The perilous narrow ocean parts asunder.

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts:

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them,

Printing their proud hoofs i‘th’ receiving earth;

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there, jumping o’er times,

Turning th’accomplishment of many years

Into an hourglass—for the which supply,

Admit me Chorus to this history,

Who Prologue-like your humble patience pray

Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play. Exit

The brightest heaven of invention:

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act,

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene.

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

Leashed in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire

Crouch for employment. But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraisèd spirits that hath dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object. Can this cock-pit hold

The vasty fields of France? Or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O pardon: since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million,

And let us, ciphers to this great account,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high uprearèd and abutting fronts

The perilous narrow ocean parts asunder.

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts:

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them,

Printing their proud hoofs i‘th’ receiving earth;

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there, jumping o’er times,

Turning th’accomplishment of many years

Into an hourglass—for the which supply,

Admit me Chorus to this history,

Who Prologue-like your humble patience pray

Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play. Exit

Other books

The Secret of Rover by Rachel Wildavsky

To Tame A Countess (Properly Spanked Book 2) by Annabel Joseph

Desert Heat by Kat Martin

A Partial History of Lost Causes by Jennifer Dubois

Fire and Rain by David Browne

Triton by Dan Rix

The Killing League by Dani Amore

The Graves of the Guilty (Hope Street Church Mysteries Book 3) by Ellery Adams

Hazardous Goods (Arcane Transport) by Mackie, John

Range War (9781101559215) by Cherryh, C. J.