Winter Brothers (29 page)

Authors: Ivan Doig

The Cracked Canoe

Â

T

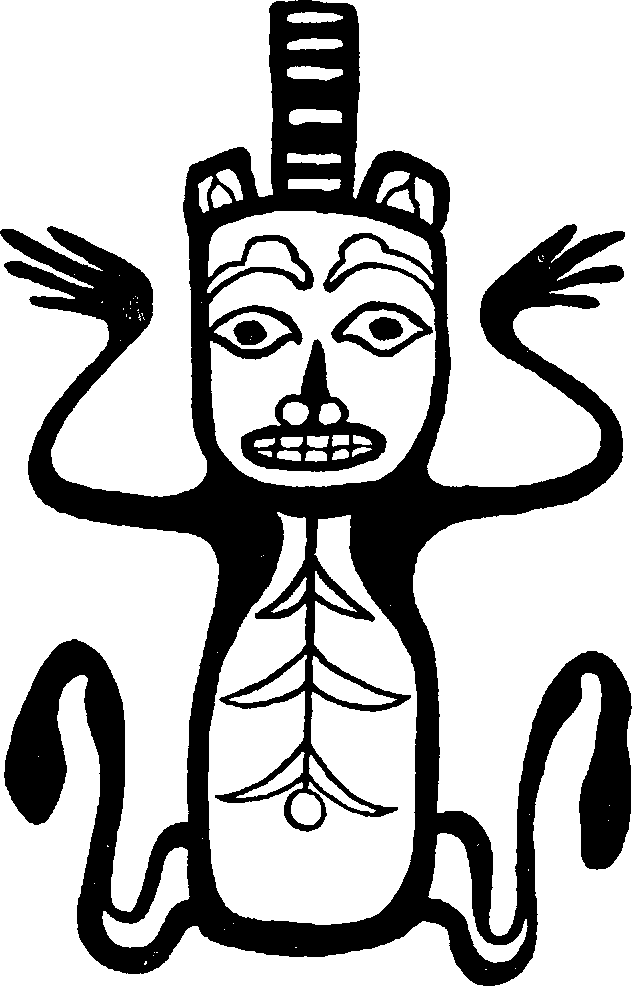

CHIMOSE

A mythological animal residing in the ocean.

I flip the month on the photo calendar above my desk, and the room fills with lumberjacks. The calendar came as a gift, a dozen scenes from the glass plates of a photographer who roved the Olympic Peninsula lumber camps in the first years of this century, and I've paid no particular attention to the scenery atop the days: January a stand of age-silvered trees, February a few dodgy sawyers off in the middle distance from the camera. But March's four loggers, spanned across the cut they are making in a cedar tree as big in diameter as this room, hover in as if estimating the board footage my desktop would yield.

The chunky logger at the left stands on a springboard, his axe held extended, straight out and waist-high, in his left hand and the blade resting almost tenderly against the gash in the cedar. He is like a man fishing off a bridge beam, but absent-mindedly having picked up the camp axe instead of the trout rod.

The next man is seated in the cut, legs casually dangling and crossed at the ankles, a small shark's grin of spikes made by the bottoms of his caulked boots. His arms are folded easily across his middle; he has trimly rolled his pant legs and sleeves; is handsome and dark-browed with a ladykilling lock of hair down the right side of his forehead.

The woodman beside him is similarly seated, arms also crossed, but is flap-eared, broad hipped, mustached. Surely he is the Swede of the crew, whatever his origins.

The final logger, on the right edge of the photo, is a long-faced giant. As he stands atop a log with his right foot propped on the cut, broad left hand hooked into a suspender strap where it meets his pants, there is unnatural length to his huge stretched body. The others must call him Highpockets. Or Percival, if that is what he prefers. His shirt is work-soiled, his eyes pouchy but hard. Unlike his at-ease mate across the tree, he clenches his axe a third of the way up the handle, as if having tomahawked it into the tree just over the left jug ear of the Swede.

Down the middle of the picture, between the seated sawyers, stands their glinting crosscut saw. If the giant is six and a half feet tall as he looks to be, the saw is ten; the elongated great-granddaddy of the crosscut in Trudy and Howard's cabin. Under its bright ladder of teeth are strewn the chips from the cut. The foursome has not much more than started on the great cedar, and already the woodpile is considerable.

Twenty days until spring in the company of these timber top-plers, and by-God forceful company they promise to be. I want all at once to see the Peninsula woods that drew whackers like these, if only to reassure myself that they're not out there now leveling daylight into whatever green is left. Late tomorrow, Carol will be finished teaching her week's classes. We will head for the Hoh rain forest.

Â

Swan at Kioosta, his forty-eighth day in the Queen Charlotte islands and his fourth on the venture along the western shore:

Very disagreeable morning, thick with misty rain.

He decides to sit tight and do such diary matters as ruminating on the blessed

total absence of fleas and other annoying insects so common and universal in Indian camps and villages....Edinso says that formerly fleas were very numerous, and at Masset they were so plentiful as the sand on the beach and they remained as long as the Indians dressed in otter'skins and bark robes, but when the white men came with other hind of clothing and bought all the old fur dresses, the fleas began to disappear. At last the Indians all went to Victoria, and on their return they found that the fleas had entirely left....Edinso said perhaps the world turned over and all the fleas hopped off.

Sunshine, bright as ripe grain. Just before lunch as I looked out wishing for birds, a cloud of bushtits and chickadees imploded into the backyard firs. I stepped into the yard to listen to their

dee dee dee

chorus, watched them become fast flecks among the branches.

No sooner had I come inside than the lion-colored cat, pausing for a slow slitted look in the direction of the sun, lazed up the hillside into the long grass.

Three times in four minutes he tried to nest himself. Then sat casually and eyed a number of items he evidently had never noticed before, such as his own tail, a bug in the grass, every nearby tree. Sneezed, and was astonished about it. I have decided there is no worry about him marauding the birds. More prospect the birds will mistake him for a fluffy boulder, perch atop him and drown him in droppings.

Â

Now to Swan. Sunday, the twelfth of August, he arises at five intending an early start downcoast from the North Island waters, the cornering turn which will take the expedition at last along the Queen Charlottes' west shore. Arises and feels a southeast wind on his face and peers seaward to

a brilliant and perfect rainbow, a double one, which indicated rain.

Within half an hour the downpour has begun.

I am disappointed as there is nothing to prevent our going but the rain, and I am anxious to be moving.

Â

That double rainbow, signal to Northwest rain, indeed must have been an “anxious” omen to Swan. Dampness is a price humankind hates to pay. (“Eleven days rain, and the most disagreeable time I have experienced,” wrote an edgy Captain William Clark on November 17, 1805, and that was at the very

start

of the Lewis and Clark expedition's sodden months in winter camp near the mouth of the Columbia.) Perhaps it is because rain tugs all that is human in us too far back to our undry origins. If it has taken this long to encase us, set us upright and mobile on frames of bone, and all that evolving can be pattered back to sheer existence by drops of water, we are not safe. No, I think the private red streams in us do not at all like that call of commonality, and the unease of it now must be in Swan.

Â

Monday, thirteenth of August,

a most disagreeable day, misty rain and alternate showers. I remained in my tent most of the time, writing and drawing, but the rain prevented out of door sketching.

Edinso's sprained back also remains a bother.

Yesterday he put some hot sand in a sack and...sweated the part;

now evidently has taken cold.

This makes it disagreeable to us as well as painful to him.

The ailing chief passes the day by having

several messes of boiled halibut served up till Mr. Deans and I were surfeited.

Meanwhile, Swan adds, one of the paddlers is busy at the fire forging

a lot of square staples to mend our canoe which had got split along the bottom.

Â

The cracked canoe creates a new fret, and Swan's most serious yet. Cedar canoes such as those of the Haidas were so finely honed, so extreme an alchemy of tree-into-vessel-of-grace (recall the Masset canoe maker Swan watched stretching an amidship portion to double its natural width) that their beautiful tension of design became a kind of fragility. For all their length and capacity they were thin, thin craft, leanest of wood. Think of this: you are in a twin-engined aircraft and one propellor begins to stutter, semaphores an erratic pattern in from the wing to your solid stare. There, maybe, is something like the jagged message Swan must read now from the canoe bottom.

To me, Swan exactly here is tested as a true explorer, for this is the first deep nip of predicament. Predicament somehow shadows an expeditionary in strange forms that cannot be imagined until the pounce happens. The Antarctic explorer Mawson, the bottoms of his feet dropping off like insoles, forcing him to bare his body for periods so the polar sun might bathe germs from it. Meriwether Lewis, on his way home down the Missouri after the two-year expedition to the Pacific, wounded in a buttock when one of his hunters mistook him for an elk. Swan's confrontation with predicament is not yet so dire, but as odd: the canoe which he has chosen as the single capable implement to carry him along the west shore now becomes threat to the journey. And dependent for safety on Edinso's canoe, which like its owner has endured considerably past spryness, are Swan, Johnny Kit Elswa, Deans, the chief himself, the chief's wife, the five crew members: ten persons, plus full supplies, plus Swan's hefty tanks of fish specimens.

It can be imagined that Swan watches carefully, hawk-intent, as the copper staples are tacked into place along the fissure through which the Pacific could come in, and the entire expedition dribble out. Then that he puffs a long moment on his white meerschaum before saying aloud that in the morning they will push on.

Â

The rain has gone by morning, and on the ebb tide they set out again, Swan uneasy about the canoe bottom

but as I know Edinso is careful I don't think he will take any chances although I expect we will get some of our things wet, and we may have to lighten the canoe by throwing some part of our cargo overboard.

That put away in the diary,

we moved and paddled along, noting everything of interest in this, to me, most interesting region.

Rounding Cape Knox, a long promontory which on the map looks ominously like a canoe flipped on its back, Swan and crew meet a headwind which forces them to land on a rocky point and scramble for a camping site. They find a place sheltered from the rain by spruce trees and high grass. With tents up and a fire going, Swan decides to lift the party's spirits.

This is a pretty rough time, with wind and rain, so to mark the event I had a ham cut and some slices fried for supper.

The ham and a good campsite warm Swan's sense of whimsy.

This same place had been occupied as a camp last summer by Count Luboff, a Russian who was looking at lands for parties in Victoria. He had put up a notice on a board, that the place was taken as a coal claim. Some of the Indians not knowing what the board meant, split it up for fire wood, which was the best use that the board could be dedicated to, as there is no coal or any indications of coal at this place except the charred remains of Count Luboffs fire.

Â

I have said Swan's trio of diaries tell very nearly as much as possible about this expedition, but there is an omission noticeable by now. The phantom of these pages is Deans. Johnny Kit Elswa and Edinso receive their ample share from Swan's pen, but the British Columbia Indian agent is mentioned only when he goes prospecting or accompanies Swan into a burial cave. The notations are unfailingly polite: too polite, as though the diarist does not want any commotion if wrong eyes find the pages.

Swan, I am beginning to think, may wish that Deans still was on the dock back at Victoria.

Â

The rain keeps onâ

Our situation is more romantic than pleasant

âand the expedition hunkers in for another day.

Swan passes it by sketching

the stone doctor...

a

sandstone reef washed by the surf into a form that certainly does not require much imagination to make one think as the Indians do that it is a giant doctor of ancient times petrified and fossilized....

Perhaps inspired by the offshore medicine man, Swan now concocts a salve of spruce gum and deer tallow for Edinso's ailing back. If not cured, the chief at least is assuaged. He bestows a pair of shark teeth ear ornaments on Swan in return.

Â

The weathered-in site atop Cape Knox begins to pall on Swan.

This delay, and Edinso's sickness makes me feel pretty blue...as I must pay for every day these people are with me....

At 2 P.M. a schooner on the offing bound south with all sails

set...A pleasant sight as there is nothing between us at this camp, and Japan, nothing but a dreary stretch of wild and monotonous ocean...the swiftly moving vessel gave a feeling of life....I am quite tired of this place and long to leave it.

Â

The last of dusk on the Olympic Peninsula. Beyond Lake Quinault, northward along the Pacific edge of the Peninsula, we are passing through miles of tunnel of high firs. The line of sky is so narrow between the margins of our deep road-canyon that it looks like a blue path somehow hung along the treetops. I am sagging from the day of deciphering Swan's travel, readying for our own; Carol with her better attention to the dark drives this last blackening stretch of distance.

Mapping in my mind as the road slits the forest, I realize that the coast here, off through the timber to the west of us, is the single piece of Washington's ocean shoreline never visited by Swan. He came as far north as the mouth of the Quinault River in 1854, on that jesting report from the Shoal water Indians that a British steamship was carrying on a smuggling trade with the Quinaults, and he once canoed down from Neah Bay to the Quillayute tribe at La Push. Between, the stretch of shore where the Hoh River flows into the Pacific, Swan somehow did not attain. But the two of us in this fat pellet of metal have, on some tideline wander or another. I think over the fact of having set foot anywhere along this continental rim where the wandersome Swan didn't, and of sleeping tonight beside a fine Peninsula river he somehow never saw, and the surprise of it whirls to me out of the rushing dark.