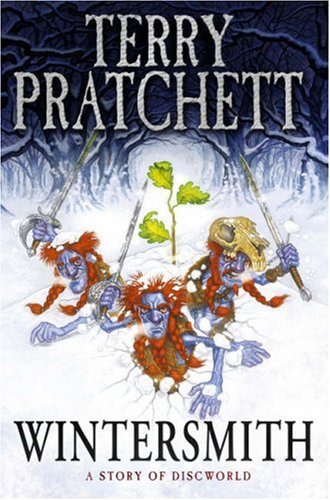

Wintersmith

Authors: Terry Pratchett

Tags: #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #General, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Children's Books - Young Adult Fiction, #Action & Adventure - General, #Science Fiction; Fantasy; Magic, #YA), #Fantasy & magical realism (Children's, #Children's Fiction

Wintersmith

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | ||

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | | |

| | |

A Feegle Glossary, adjusted for

those of a delicate disposition

(A Work in Progress by Miss Perspicacia Tick)

Bigjobs:

Human beings.

Big Man:

Chief of the clan (usually the husband of the kelda).

Blethers:

Rubbish, nonsense.

Boggin’:

To be desperate, as in “I’m boggin’ for a cup of tea.”

Bunty:

A weak person.

Cack yer kecks:

Er, to put it delicately…to be very, very frightened. As it were.

Carlin:

Old woman.

Cludgie:

The privy.

Crivens!:

A general exclamation that can mean anything from “My goodness!” to “I’ve just lost my temper and there is going to be trouble.”

Dree your/my/his/her weird:

Face the fate that is in store for you/me/him/her.

Een:

Eyes.

Eldritch:

Weird, strange. Sometimes means oblong, too, for some reason.

Fash:

Worry, upset.

Geas:

A very important obligation, backed up by tradition and magic. Not a bird.

Gonnagle:

The bard of the clan, skilled in musical instruments, poems, stories, and songs.

Hag:

A witch of any age.

Hag o’ hags:

A very important witch.

Hagging/Haggling:

Anything a witch does.

Hiddlins:

Secrets.

Kelda:

The female head of the clan, and eventually the mother of most of it. Feegle babies are very small, and a kelda will have hundreds in her lifetime.

Lang syne:

Long ago.

Last World:

The Feegles believe that they are dead. This world is so nice, they argue, that they must have been really good in a past life and then died and ended up here. Appearing to die here means merely going back to the Last World, which they believe is rather dull.

Mudlin:

Useless person.

Pished:

I am assured that this means “tired.”

Schemie:

An unpleasant person.

Scuggan:

A really unpleasant person.

Scunner:

A generally unpleasant person.

Ships:

Woolly things that eat grass and go baa. Easily confused with the other kind.

Spavie:

See Mudlin.

Special Sheep Liniment:

Probably moonshine whisky, I am very sorry to say. No one knows what it’d do to sheep, but it is said that a drop of it is good for shepherds on a cold winter’s night and for Feegles at any time at all. Do not try to make this at home.

Spog:

A leather pouch, worn on the front of his belt, where a Feegle keeps his valuables and uneaten food, interesting insects, useful bits of twig, lucky dirt, and so on. It is not a good idea to fish around in a spog.

Steamie:

Found only in the big Feegle mounds in the mountains, where there’s enough water to allow regular bathing; it’s a kind of sauna. Feegles on the Chalk tend to rely on the fact that you can get only so much dirt on you before it starts to fall off of its own accord.

Waily:

A general cry of despair.

The Big Snow

W

hen the storm came, it hit the hills like a hammer. No sky should hold as much snow as this, and because no sky could, the snow fell, fell in a wall of white.

There was a small hill of snow where there had been, a few hours ago, a little cluster of thorn trees on an ancient mound. This time last year there had been a few early primroses; now there was just snow.

Part of the snow moved. A piece about the size of an apple rose up, with smoke pouring out around it. A hand no larger than a rabbit’s paw waved the smoke away.

A very small but very angry blue face, with the lump of snow still balanced on top of it, looked out at the sudden white wilderness.

“Ach, crivens!” it grumbled. “Will ye no’ look at this? ’Tis the work o’ the Wintersmith! Noo there’s a scunner that willna tak’ ‘no’ fra’ an answer!”

Other lumps of snow were pushed up. More heads peered out.

“Oh waily, waily, waily!” said one of them. “He’s found the big wee hag again!”

The first head turned toward this head, and said, “Daft Wullie?”

“Yes, Rob?”

“Did I no’ tell ye to lay off that waily business?”

“Aye, Rob, ye did that,” said the head addressed as Daft Wullie.

“So why did ye just do it?”

“Sorry, Rob. It kinda bursted oot.”

“It’s so dispiritin’.”

“Sorry, Rob.”

Rob Anybody sighed. “But I fear ye’re right, Wullie. He’s come for the big wee hag, right enough. Who’s watchin’ over her doon at the farm?”

“Wee Dangerous Spike, Rob.”

Rob looked up at clouds so full of snow that they sagged in the middle.

“Okay,” he said, and sighed again. “It’s time fra’ the Hero.”

He ducked out of sight, the plug of snow dropping neatly back into place, and slid down into the heart of the Feegle mound.

It was quite big inside. A human could just about stand up in the middle, but would then bend double with coughing because the middle was where there was a hole to let smoke out.

All around the inner wall were tiers of galleries, and every one of them was packed with Feegles. Usually the place was awash with noise, but now it was frighteningly quiet.

Rob Anybody walked across the floor to the fire, where his wife, Jeannie, was waiting. She stood straight and proud, like a kelda should, but close up it seemed to him that she had been crying. He put his arm around her.

“All right, ye probably ken what’s happenin’,” he told the blue-and-red audience looking down on him. “This is nae common storm. The Wintersmith has found the big wee hag—noo then, settle doon!”

He waited until the shouting and sword rattling had died down, then went on: “We canna fight the Wintersmith for her! That’s her road! We canna walk it for her! But the hag o’ hags has set us on another path! It’s a dark one, and dangerous!”

A cheer went up. Feegles liked the idea of this, at least.

“Right!” said Rob, satisfied. “Ah’m awa’ tae fetch the Hero!”

There was a lot of laughter at this, and Big Yan, the tallest of the Feegles, shouted, “It’s tae soon. We’ve only had time tae gie him a couple o’ heroing lessons! He’s still nae more than a big streak o’ nothin’!”

“He’ll be a Hero for the big wee hag and that’s an end o’ it,” said Rob sharply. “Noo, off ye go, the whole boilin’ o’ ye! Tae the chalk pit! Dig me a path tae the Underworld!”

It had to be the Wintersmith, Tiffany Aching told herself, standing in front of her father in the freezing farmhouse. She could feel it out there. This wasn’t normal weather even for midwinter, and this was springtime. It was a challenge. Or perhaps it was just a game. It was hard to tell, with the Wintersmith.

Only it can’t be a game because the lambs are dying. I’m only just thirteen, and my father, and a lot of other people older than me, want me to do something. And I can’t. The Wintersmith has found me again. He is here now, and I’m too weak.

It would be easier if they were bullying me, but no, they’re begging. My father’s face is gray with worry and he’s begging.

My father is begging me.

Oh no, he’s taking his hat off. He’s

taking off his hat

to speak to me!

They think magic comes free when I snap my fingers. But if I can’t do this for them, now, what good am I? I can’t let them see I’m afraid. Witches aren’t allowed to be afraid.

And this is my fault. I: I started all this. I must finish it.

Mr. Aching cleared his throat.

“…And, er, if you could…er, magic it away, uh, or something? For us…?”

Everything in the room was gray, because the light from the windows was coming through snow. No one had wasted time digging the horrible stuff away from the houses. Every person who could hold a shovel was needed elsewhere, and still there were not enough of them. As it was, most people had been up all night, walking the flocks of yearlings, trying to keep the new lambs safe…in the dark, in the snow….

Her

snow. It was a message to her. A challenge. A summons.

“All right,” she said. “I’ll see what I can do.”

“Good girl,” said her father, grinning with relief. No, not a good girl, thought Tiffany. I brought this on us.

“You’ll have to make a big fire, up by the sheds,” she said aloud. “I mean a big fire, do you understand? Make it out of anything that will burn, and you must keep it going. It’ll keep trying to go out, but you must keep it going. Keep piling on the fuel, whatever happens.

The fire must not go out!

”

She made sure that the “not!” was loud and frightening. She didn’t want people’s minds to wander. She put on the heavy brown woollen cloak that Miss Treason had made for her and grabbed the black pointy hat that hung on the back of the farmhouse door. There was a sort of communal grunt from the people who’d crowded into the kitchen, and some of them backed away. We want a witch now, we need a witch now, but—we’ll back away now, too.

That was the magic of the pointy hat. It was what Miss Treason called “Boffo.”

Tiffany Aching stepped out into the narrow corridor that had

been cut through the snow-filled farmyard where the drifts were more than twice the height of a man. At least the deep snow kept off the worst of the wind, which was made of knives.

A track had been cleared all the way to the paddock, but it had been heavy going. When there are fifteen feet of snow everywhere, how can you clear it? Where can you clear it to?

She waited by the cart sheds while the men hacked and scraped at the snowbanks. They were tired to the bone by now; they’d been digging for hours.

The important thing was—

But there were lots of important things. It was important to look calm and confident, it was important to keep your mind clear, it was important not to show how pants-wettingly scared you were….

She held out a hand, caught a snowflake, and took a good look at it. It wasn’t one of the normal ones, oh no. It was one of his special snowflakes. That was nasty. He was taunting her. Now she could hate him. She’d never hated him before. But he was killing the lambs.

She shivered and pulled the cloak around her.

“This I choose to do,” she croaked, her breath leaving little clouds in the air. She cleared her throat and started again. “This I choose to do. If there is a price, this I choose to pay. If it is my death, then I choose to die. Where this takes me, there I choose to go. I choose. This I choose to do.”

It wasn’t a spell, except in her own head, but if you couldn’t make spells work in your own head, you couldn’t make them work at all.

Tiffany wrapped her cloak around her against the clawing wind and watched dully as the men brought straw and wood. The fire

started slowly, as if frightened to show enthusiasm.

She’d done this before, hadn’t she? Dozens of times. The trick was not that hard when you got the feel of it, but she’d done it with time to get her mind right, and anyway, she’d never done it with anything more than a kitchen fire to warm her freezing feet. In theory it should be just as easy with a big fire and a field of snow, right?

Right?

The fire began to roar up. Her father put his hand on her shoulder. Tiffany jumped. She’d forgotten how quietly he could move.

“What was that about choosing?” he said. She’d forgotten what good hearing he had, too.

“It’s a…witch thing,” she answered, trying not to look at his face. “So that if this…doesn’t work, it’s no one’s fault but mine.” And this is my fault, she added to herself. It’s unfair, but no one said it wasn’t going to be.

Her father’s hand caught her chin and gently turned her head around. How soft his hands are, Tiffany thought. Big man’s hands but soft as a baby’s, because of the grease on the sheep’s fleeces.

“We shouldn’t have asked you, should we…” he said.

Yes, you should have asked me, Tiffany thought. The lambs are dying under the dreadful snow. And I should have said no, I should have said I’m not that good yet. But the lambs are dying under the dreadful snow!

There will be other lambs, said her Second Thoughts.

But these aren’t those lambs, are they? These are the lambs that are dying, here and now. And they’re dying because I listened to my feet and dared to dance with the Wintersmith.

“I can do it,” she said.

Her father held her chin and stared into her eyes.

“Are you sure, jiggit?” he asked. It was the nickname her grandmother had had for her—Granny Aching, who never lost a lamb to the dreadful snow. He’d never used it before. Why had it risen up in his mind now?

“Yes!” She pushed his hand away, and broke his gaze before she could burst into tears.

“I…haven’t told your mother this yet,” said her father very slowly, as if the words required enormous care, “but I can’t find your brother. I think he was trying to help. Abe Swindell said he saw him with his little shovel. Er…I’m sure he’s all right, but…keep an eye open for him, will you? He’s got his red coat on.”

His face, with no expression at all, was heartbreaking to see. Little Wentworth, nearly seven years old, always running after the men, always wanting to be one of them, always trying to help…how easily a small body could get overlooked…. The snow was still coming fast. The horribly wrong snowflakes were white on her father’s shoulders. It’s these little things you remember when the bottom falls out of the world, and you’re falling—

That wasn’t just unfair; that was…cruel.

Remember the hat you wear! Remember the job that is in front of you! Balance! Balance is the thing. Hold balance in the center, hold the balance….

Tiffany extended her numb hands to the fire, to draw out the warmth.

“Remember, don’t let the fire go out,” she said.

“I’ve got men bringing up wood from all over,” said her father. “I told ’em to bring all the coal from the forge, too. It won’t run out of feeding, I promise you!”

The flame danced and curved toward Tiffany’s hands. The trick was, the trick, the trick…was to fold the heat somewhere close,

draw it with you and…balance. Forget everything else!

“I’ll come with—” her father began.

“No! Watch the fire!” Tiffany shouted, too loud, frantic with fear. “You will do what I say!”

I am not your daughter today! her mind screamed. I am your witch!

I

will protect

you

!

She turned before he could see her face and ran through the flakes, along the track that had been cut toward the lower paddocks. The snow had been trodden down into a lumpy, hummocky path, made slippery with fresh snow. Exhausted men with shovels pressed themselves into the snowbanks on either side rather than get in her way.

She reached the wider area where other shepherds were digging into the wall of snow. It tumbled in lumps around them.

“Stop! Get back!” her voice shouted, while her mind wept.

The men obeyed quickly. The mouth that had given that order had a pointy hat above it. You didn’t argue with that.

Remember the heat, the heat, remember the heat, balance, balance…

This was witching cut to the bone. No toys, no wands, no Boffo, no headology, no tricks. All that mattered was how good you were.

But sometimes you had to trick yourself. She wasn’t the Summer Lady and she wasn’t Granny Weatherwax. She needed to give herself all the help she could.

She pulled the little silver horse out of her pocket. It was greasy and stained, and she’d meant to clean it, but there had been no time, no time….

Like a knight putting on his helmet, she fastened the silver chain around her neck.

She should have practiced more. She should have listened to

people. She should have listened to herself.

She took a deep breath and held out her hands on either side of her, palms up. On her right hand a white scar glowed.

“Thunder on my right hand,” she said. “Lightning in my left hand. Fire behind me. Frost in front of me.”

She stepped forward until she was only a few inches away from the snowbank. She could feel its coldness already pulling the heat out of her. Well, so be it. She took a few deep breaths. This I choose to do….

“Frost to fire,” she whispered.

In the yard, the fire went white and roared like a furnace.

The snow wall spluttered and then exploded into steam, sending chunks of snow into the air. Tiffany walked forward slowly. Snow pulled back from her hands like mist at sunrise. It melted in the heat of her, becoming a tunnel in the deep drift, fleeing from her, writhing around her in clouds of cold fog.

Yes! She smiled desperately. It was true. If you had the perfect center, if you got your mind right, you could balance. In the middle of the seesaw is a place that never moves….

Her boots squelched over warm water. There was fresh green grass under the snow, because the awful storm had been so late in the year. She walked on, heading to where the lambing pens were buried.

Her father stared at the fire. It was burning white-hot, like a furnace, eating through the wood as if driven by a gale. It was collapsing into ashes in front of his eyes….