Wm & H'ry: Literature, Love, and the Letters Between Wiliam and Henry James (5 page)

Read Wm & H'ry: Literature, Love, and the Letters Between Wiliam and Henry James Online

Authors: J. C. Hallman

Tags: #History, #Philosophy, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #Biographies & Memoirs, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Arts & Literature, #Modern, #Philosophers, #Professionals & Academics, #Authors, #19th Century, #Literature & Fiction

time along of ours, and

then off they whirl again

into the unknown, leaving us with little more

than an impression of their reality and a feeling

of baffled curiosity as to the mystery of the

beginning and end of their being.

Emphasis on “

whirl

,”

which speaks to the core of the brothers’ similar take on reality and their differences

as to what ought to be done about it.

“Whirl” returns to Shakespeare, whose influence for

Wm stretched all the way back to his very first letter,

and who, for H’ry, was so “immense” that one “need

not press the case of his example.” The letters cite

Shakespeare often, without quotation marks, such as

when H’ry, in 13, complained of an overfull work

schedule and social obligations: “It is again the whirli-

gig of time.” That this slightly distorted

Twelfth Night

’s original meaning does not seem to have bothered

Wm, who four years later, in complaining of a speak-

ing engagement at a crowded park, hewed closer to

31

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 31

9/4/12 6:26 PM

H’ry’s meaning: “It’s a strange freak of the whirligig

of fortune that finds me haranguing the multitude on

Boston Common.” Wm had a particular fondness for

the word. In 1, writing to Oliver Wendell Holmes

Jr., he claimed that a sadness that had descended upon

him was due to ghosts “dancing a senseless whirligig”

about him, and in an 1 essay he claimed that as soon

as “the whirligig of time goes round,” science would

appear shortsighted for having preferred an imper-

sonal worldview to a personal one. H’ry must have

taken careful note as “whirligigs” appeared serially in

The Principles of Psychology

,

in

The Will to Believe

,

in a speech that H’ry praised in 103 (“your beautiful Harvard address”), and in a plaintive 105 letter regretting the increasing infrequency of their correspondence:

“The wheel of life seems to be whirling for each of us

in such wise that we ‘don’t write.’” A few years later, in

The American Scene

,

H’ry set out to prove that he could stretch Shakespeare’s metaphor just as easily as he had

stretched the stream of consciousness:

The term I use may appear extravagant, but it

was a fact, none the less, that I seemed to take full

in my face, on this occasion, the cold stir of air

32

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 32

9/4/12 6:26 PM

produced when the whirligig of time has made

one of its liveliest turns. It is always going, the

whirligig, but its effect is so to blow up the dust

that we must wait for it to stop a moment, as it

now and then does with a pant of triumph, in

order to see what it has been at.

Of the many attempts that have been made to distill

the brothers’ essential differences, none works quite so

simply or succinctly as the snipping away of “gig” from

“whirligig.” If “whirligig,” as a name for a twirling gadget, relies on Cartesian philosophy and characterizes

the universe as a simple turning machine susceptible to

comprehension and repair, then “whirl” melts the im-

age (for example, “whirlpool”), and proposes that the

only true solace comes from renderings of the whirling

world whose accuracy makes bearable the turbulence

of our own streams. Wm clearly preferred the former:

when he came round to proposing his grand fix for the

problem of truth in philosophy, pragmatism, he de-

fined it, in part, as a “method,” echoing the “method of

truth” that H’ry had found lacking in George Sand. In

preferring the latter, H’ry proposed a different method

for a different purpose. He did not aim for a unified

33

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 33

9/4/12 6:26 PM

theory of truth; rather, adherence to a better, fluid

realism—a realism that did not substitute certainty

and simplicity for the universe’s irreducible spiraling

complex ambiguity—is the thread woven through his

career: it’s the figure in his carpet.

But how exactly should one be a weaver of stories,

when storytelling itself, as H’ry noted in “The Lesson

of Balzac,” tended to organize unruly reality into ruled

scenes? H’ry’s work proposed multiple solutions. Nar-

rators in H’ry’s early stories balk at their own omni-

science (“If I were telling my story from Mrs. Mason’s

point of view . . . I might make a very good thing of the statement that this lady had deliberately and solemnly

conferred . . . upon my hero; but I am compelled to

let it stand in this simple shape”). His dialogue—mad-

deningly, for Wm—focused as much on the chaos of

actual human speech as it did on clearly conveying the

content of the conversations described. Wm recognized

the variety of H’ry’s techniques even if he couldn’t

wholly sign on to them: he lamented the losing of “the

story in the sand” at the end of

The Tragic Muse

, but admitted “that is the way things lose themselves in real

life.” Late in their lives Wm made special mention of

H’ry’s preface to

The Wings of the Dove

: it “throws much 34

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 34

9/4/12 6:26 PM

psychologic light on your creative process.” Here, H’ry

had acknowledged that his goal in the story of a dying

young woman and the small cast of characters caught

in the orbit of her demise was to depict the growing,

changing consciousness of a girl, but to “approach her

circuitously . . . as an unspotted princess is ever dealt with.” He was elaborating on the story itself, and the

novel’s own description of Milly Theale defends his

better realism:

She worked—and seemingly quite without

design—upon the sympathy, the curiosity, the

fancy of her associates, and we shall really

ourselves scarce otherwise come closer to her

than by feeling their impression and sharing, if

need be, their confusion.

They often returned to that word—“impression”—in

both work and letters.

On April 2, 1, H’ry began a letter from Oxford

that would take him four days to complete. He was

replying to a malaise that Wm had been suffering for

some time at home, having been laid low by his back

35

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 35

9/4/12 6:26 PM

and frustrated ambitions. H’ry encouraged him to

“spurn the azure demon,” and take heart from H’ry’s

own “adventures.” How could Wm do that? H’ry sat

down after dinner to record a walk he’d taken earlier

in the afternoon. “I feel as if I should like to make a

note of certain recent impressions,” he wrote, “before

they quite fade out of my mind.” He proceeded with a

story in which he acted as postman, walking through

Oxford’s colleges to deliver a letter for a friend:

It was a perfect evening & in the interminable

British twilight the beauty of the whole place

came forth with magical power. There are no

words for these colleges. As I stood last eveg.

within the precincts of mighty Magdalen,

gazed at its great serene tower & uncapped my

throbbing brow in the wild dimness of its courts,

I thought that the heart of me would crack with

the fulness of satisfied desire.

The chronicle continues likewise for several pages. The

goal of the impressions is to get Wm as close as possible to H’ry’s “throbbing brow,” and thereby enable him to

endure his dark mood. The value of recorded impres-

sions could be applied to art as easily as to strolls, and 36

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 36

9/4/12 6:26 PM

a few months later, now in Rome, H’ry harkened back

to Wm’s complaint about Herman Grimm’s want of

animal spirits in describing his viewing of the paint-

ings of Tintoretto: “I never manage to write but a very

small fraction of what has originally occurred to me.

What you call the ‘animal heat’ of contemplation is

sure to evaporate within half an hour.”

Long before the surviving correspondence begins,

Wm and H’ry gestated together in the womb of art,

forging their brotherhood in wandering turns through

museums in Paris and London. When Wm studied

painting in the Newport studio of William Henry Hunt

in 10—at the time, landscape artist John La Farge was

the only other student—H’ry tagged along, sometimes

dabbling with drawings of his own.

“Your eyes are windows through which you receive

impressions,” Hunt told them, “keeping yourself as

passive as warm wax, instead of being active.” This

maybe helps to explain why Wm abandoned art; biog-

raphers would later describe his personality in child-

hood as marked by “activity”; he was outgoing and

extroverted. H’ry, by way of contrast, was marked by

“passivity”; he was quiet, and lived in a “world of ‘im-

pressions.’” H’ry had no talent as a painter, yet the time 37

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 37

9/4/12 6:26 PM

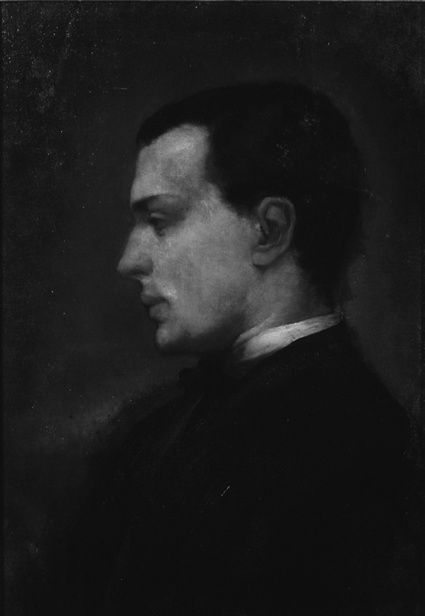

proved formative for him anyway: La Farge, who once

painted H’ry’s portrait, is credited with introducing

H’ry to Balzac and with helping to steer him toward

writing with the observation that all the arts are one.

(

The Tragic Muse

’s Nick Dormer: “All art is one—re-member that, Biddy dear.”)

The great truth and task of the universe, as both

brothers saw it, now seems to congeal: we are all of

us hopelessly awash inside a whipping, whirling, ac-

celerating rush of facts, images, incidents, experiences, 38

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 38

9/4/12 6:26 PM

all of which buffet up against us, strike us, pound us,

concuss

us, leaving us battered, dented,

impressed and

depressed

, until we find a way to usefully surf the whirling current. H’ry was first to fashion a seaworthy vessel in the form of a career, navigating his way to a viable

channel long before Wm did. Wm’s dark mood of the

late 10s—a crisis that appears thinly disguised as a

case study of the “sick soul” in

The Varieties of Religious

Experience

—can be attributed to an inability to plot a singular course through a hurricane of impressions.

Wm famously hoisted himself out of his malaise

with the work of Charles Renouvier and the decision

to believe in free will, but if from there he came to

think that a professional voyage into the science of the

mind would float him to a more comfortable home,

he must have been disappointed. The preeminent phi-

losopher of the mind at the time was Herbert Spencer.

In “Brute and Human Intellect,” Wm dismissed Spen-

cer’s view with a characterization that sounds eerily

like Hunt’s advice: “[Spencer] regards the creature as

absolutely passive clay, upon which ‘experience’ rains

down. The clay will be impressed most deeply where

the drops fall thickest, and so the final shape of the

mind is moulded.” The problem with this was that

39

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 39

9/4/12 6:26 PM

it ignored the will that saved Wm. It implied that all

experiences were the same, which even casual intro-

spection could reject. “My experience is what I agree to

attend to,” Wm argued back. “Only those items which

I notice shape my mind—without selective interest,

experience is an utter chaos.” In other words, once you

hitch a ride on the stream’s conveyor, you have a tool,

you have a rudder, and your consciousness is precisely

that which scoops logical sequence from sensation’s

burbling cauldron. In terms of impressions, Wm took

solace in “an admirable passage” from James Martin-

eau: “Experience proceeds and intellect is trained . . .

not by reduction of pluralities of impression to one,

but by the opening out of one into many.”

The early letters are so full of “impressions” they’re

really rough drafts of essays. Initially, for H’ry—even

though he read “Brute and Human Intellect” in 1—

impressions were less a lens through which one could

inspect psychology than they were a kind of perish-

able commodity. H’ry always wrote for money—Wm