Wm & H'ry: Literature, Love, and the Letters Between Wiliam and Henry James (7 page)

Read Wm & H'ry: Literature, Love, and the Letters Between Wiliam and Henry James Online

Authors: J. C. Hallman

Tags: #History, #Philosophy, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #Biographies & Memoirs, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Arts & Literature, #Modern, #Philosophers, #Professionals & Academics, #Authors, #19th Century, #Literature & Fiction

reach.

The Tragic Muse

’s Peter Sherringham reminds Bridget Dormer “of a Titian,” and Nick Dormer later

feels an ineffectual longing to have “a go” at Titian

and Tintoretto.

The Wings of the Dove

’s Susan Shepherd recognizes that the story’s advancing intrigue has become “a Veronese picture, as near as can be.” In both

novels, art betrays consciousness: Miriam Rooth is “apt

to drop” particular observations while “under the sug-

gestion” of Titian or Bronzino, and Milly Theale speaks

at one moment of her mysterious illness “almost as if

under [the] suggestion” of a Bronzino, and at another

finds herself surrounded by Turners and Titians at Lon-

don’s National Gallery, which seem to “[join] hands”

about her and trigger an ensuing reverie.

This last description seems almost to cite a plaintive

remark Wm once made to H’ry as his career trajectory

in science and academia began to take shape. Painting

was slipping farther and farther away:

50

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 50

9/4/12 6:26 PM

But I envy ye the world of Art. Away from

it . . . we sink into a flatter blanker kind of

consciousness, and indulge in an ostrichlike

forgetfulness of all our richest potentialities—and

they startle us now and then when by accident

some rich human product, pictorial, literary, or

architectural slaps us with its tail.

Wm had always approached art more academically

than H’ry, comparing works so as to plot the arc of

art history, attempting to gauge whether it was the

Germans or the Venetians who were the true broth-

ers of Greeks, etc. In 12, he planned an essay that

would apply natural selection to competing schools

of art—artistic Darwinism—but never executed it. By

the time of the writing of

The Principles of Psychology

,

art had receded completely, becoming less overt subject

matter than convenient metaphor. “This chapter is like

a painter’s first charcoal sketch upon his canvas,” he

wrote at the start of “The Stream of Consciousness.”

A field of grass might

appear

green, he allowed a short time later, describing the complexity of subjective sensation, “yet a painter would have to paint one part of

51

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 51

9/4/12 6:26 PM

it dark brown, another part bright yellow, to give it its real sensational effect.”

That art faded into Wm’s background just as it

climbed into H’ry’s foreground expressed figuratively

what had once been expressed literally. In 1, Wm

offered H’ry invaluable criticism in response to a long,

early story. “Gabrielle de Bergerac” employs a now-

familiar Jamesian tool: a foreground “frame tale” in

which a character somehow bequeaths a story to a

notably H’ry-like narrator, and a background tale that

is repeated for the reader. Wm objected to the ending

of “Gabrielle de Bergerac,” which after a long dip into

a background drama returns briefly to the foreground

frame tale. “Very exquisitely touched,” Wm wrote,

“but the denouement bad in that it did not end with

Coquelin’s death. . . . The end is both humdrum and

improbable.” What he meant was that the story could

remain asymmetrical. H’ry didn’t need to return to

the foreground—the story could simply fade into its

background and end there. As it happened, the interest

of backgrounds was a subject actually described in the

background story of “Gabrielle de Bergerac”: a char-

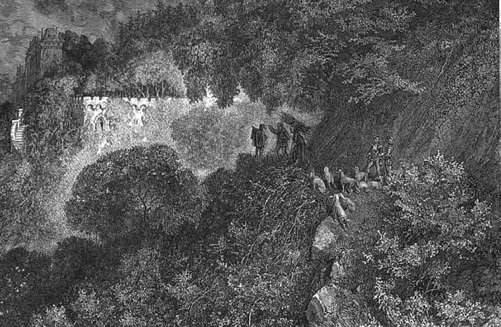

acter recalls Gustave Doré’s illustrations of Charles

Perrault’s

Sleeping Beauty

, in particular an image in 52

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 52

9/4/12 6:26 PM

which three shadowed foreground figures gesture off

to a foggy but better lit castle in the distance. It was

the light

and

the vagueness, the story claimed, that drew the eye to the rear of the image and triggered

the working of the mind:

What does the castle contain? What secret is

locked in its stately walls? What revel is enacted

in its long saloons? What strange figures stand

aloof from its vacant windows? You ask the

question, and the answer is a long revery.

For H’ry, the castle was like the citadel of conscious-

ness forever running in the background of human in-

53

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 53

9/4/12 6:26 PM

tercourse; it was the more compelling tale whirling

behind

whatever simple plots storytellers strung clumsily together. H’ry carefully applied Wm’s advice whenever

he employed the foreground frame tale in the future,

most notably in

The Turn of the Screw

,

which ends the harrowing account of the governess’s haunting with

the dramatic death of a child, and never returns to the

circle of friends who are listening to the story read

aloud around a Christmas fire.

While H’ry clearly benefited from Wm’s advice, it’s

not at all clear that Wm understood

how

his advice had become useful. Outside of stories, he wanted

nothing

left in the background. This was made apparent in

1, when Wm wrote to H’ry of visiting John La Farge

to view several paintings then still under way. One in

particular,

Paradise Valley

, a broad image of green fields near Newport, absolutely frayed Wm’s nerves. The

painting had begun with a large female figure situated

in the foreground, a white-draped presence occupying

almost two-thirds of the large canvas.

Sometime during the work on the piece, La Farge

had been moved to paint over the figure completely,

leaving only the background and a tiny baby sheep.

Wm couldn’t get his head around it. He understood

54

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 54

9/4/12 6:26 PM

the landscape, which was “as big as all out doors and

flooded with light even in its botchy state.” But he

couldn’t begin to fathom why La Farge had eliminated

the woman in the foreground. “He ought to repaint

a figure in it no matter how ‘quaint’ it will look to the vulgar.”

55

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 55

9/4/12 6:26 PM

They had begun to disagree even about what it meant

to be “vulgar.”

H’ry took his cue from Balzac.

Eugenie Grandet

’s

eponymous heroine, for example, comes from “a class

of females found in the middle ranks of life, whose

beauty appears vulgar.” But Eugenie is not vulgar her-

self: “There was nothing

pretty

about Eugenie; she was beautiful with that beauty so easily overlooked, and

which the artist alone catches.” H’ry spent a lifetime

trying to apply a similar principle to language. In “The

Question of Our Speech” (an address first delivered in

105 to an audience of “

,

or hundred

people” in Philadelphia) he warned of the “vulgarization” resulting

from “common schools and the ‘daily paper,’” and sug-

gested that “avoiding vulgarity, arriving at lucidity” was an art to be cultivated if we hoped to distinguish our

speech from “the barking or the roaring of animals.”

In other words, to be vulgar was to be less obscene

than obvious. For Wm, it had always meant something

slightly different. His pained work on the style of his

Grimm review had struck him as a balancing act be-

tween “pomposity & vulgar familiarity.” He allowed

56

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 56

9/4/12 6:26 PM

that style meant leaving the essential unspoken—of

Turgenev, he wrote in one letter, “[He] has a sense of

worlds within worlds whose existence is unsuspected

by the vulgar”—but he also equated it with the careless

redundancy of writers who fetishized an offhand air. In

13, Wm fretted over “the determination on the part

of all who write now to do it as amateurs, & never use the airs & language of a professional, to be first of all a layman & a gentleman, & to pretend that your ideas came to you accidentally.” A decade and a half earlier,

he had criticized H’ry’s stories for giving “a certain

impression of the author clinging to his gentlemanli-

ness tho’ all else be lost.”

Which was actually prescient. By the late 10s, H’ry

had begun to tire of fiction; drawn by the financial lure of the theater, he had begun dabbling as a playwright.

The public aspect of the experiment discomfited him

from the start. “There wd. be much good for me to

tell you of my Play & its successors if I were to speak of the business in any way,” he wrote in June 10.

“But I must not, for awfully good reasons, & I beseech you not to either.” It wasn’t that he was afraid; it was

that there was decorum to consider. The next month,

he calmly accepted the lackluster performance of his

57

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 57

9/4/12 6:26 PM

most recent novel. A writer couldn’t concern himself

with “popularity,” he wrote. One “must go one’s way

& know what one’s about” and understand that it was

popularity enough if a work made any “audible vibra-

tion.” A few months later, however, he could barely

contain his excitement over the preparations for the

opening of

his stage adaptation of

The American.

He apologized for his “vulgarities” in this regard; he happily related details of rehearsals, of venue, and of fu-

ture plays that might also be put into production. He

had a “kind of mystic confidence in the ultimate life of

the piece,” and claimed he had always known that plays

were the genre to which his work was most suited.

Critics disagreed;

The American

was panned. The show ran only sixty-nine nights; H’ry made no profit from it.

“TELL THIS TO NO ONE,” he told Wm.

He kept at it, frustrating as it was. Over the next

few years, he changed producers and suffered through

endless strings of setbacks and delays. H’ry wasn’t used

to working with others. “They simply kicked me . . .

out of the theatre,” he wrote in 14. “How can one

rehearse with people who are dying to get rid of you?”

H’ry hadn’t even employed a literary agent for the first

fifteen years of his career. “I can

meet

these horrors, in a 58

Hallman_firstpages5x.indd 58

9/4/12 6:26 PM

word, I think (for another year),” he wrote finally, “but I can’t

talk

about them.”

Wm valiantly resisted the urge to remind H’ry that

he had offered him fair warning. Back when H’ry first

showed interest in the theater, Wm related a story of

stumbling across a street poster advertising the attrac-

tions of a play soon to open: “NO PLOT—ALL FUN!”

“What a relief to the intellect to have

no

plot!” Wm wrote. His point was that in writing for the stage one

needed to remain vigilant to “the qualities that the

stage requires.” He advised H’ry to “cold bloodedly

throw in enough

action

to please the people.” In 14, Wm invited several friends to his summerhouse in New

Hampshire to read through several of H’ry’s plays as a

group. They were received, Wm was forced to admit,

“with a certain tinge of disappointment.” The problem

of one was that “the

matter

[was] so slight.” In another, a character failed to “show her inside nature enough.”