Woman Hating (11 page)

Women should be beautiful. All repositories of cultural wisdom from King Solomon to King Hefner agree: women should be beautiful. It is the reverence for female beauty which informs the romantic ethos, gives it its energy and justification. Beauty is transformed into that golden ideal, Beauty —rapturous and abstract. Women must be beautiful and Woman is Beauty.

Notions of beauty always incorporate the whole of a given societal structure, are crystallizations of its values. A society with a well-defined aristocracy will have aristocratic standards of beauty. In Western “democracy” notions of beauty are “democratic”: even if a woman is not born beautiful, she can make herself

attractive

.

The argument is not simply that some women are not beautiful, therefore it is not fair to judge women on the basis of physical beauty; or that men are not judged on that basis, therefore women also should not be judged on that basis; or that men should look for character in women; or that our standards of beauty are too parochial in and of themselves; or even that judging women according to their conformity to a standard of beauty serves to make them into products, chattels, differing from the farmer's favorite cow only in terms of literal form. The issue at stake is different, and crucial. Standards of beauty describe in precise terms the relationship that an individual will have to her own body. They prescribe her mobility, spontaneity, posture, gait, the uses to which she can put her body.

They define precisely the dimensions of her physical freedom.

And, of course, the relationship between physical freedom and psychological development, intellectual possibility, and creative potential is an umbilical one.

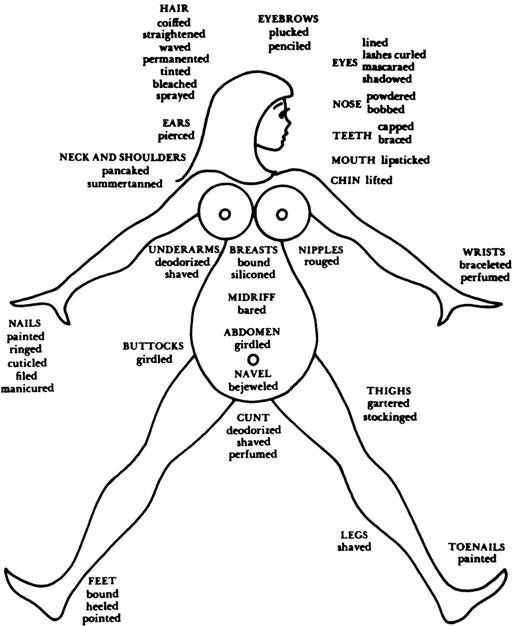

In our culture, not one part of a woman’s body is left untouched, unaltered. No feature or extremity is spared the art, or pain, of improvement. Hair is dyed, lacquered, straightened, permanented; eyebrows are plucked, penciled, dyed; eyes are lined, mascaraed, shadowed; lashes are curled, or false —from head to toe, every feature of a woman's face, every section of her body, is subject to modification, alteration. This alteration is an ongoing, repetitive process. It is vital to the economy, the major substance of male-female role differentiation, the most immediate physical and psychological reality of being a woman. From the age of 11 or 12 until she dies, a woman will spend a large part of her time, money, and energy on binding, plucking, painting, and deodorizing herself. It is commonly and wrongly said that male transvestites through the use of makeup and costuming caricature the women they would become, but any real knowledge of the romantic ethos makes clear that these men have penetrated to the core experience of being a woman, a romanticized construct.

The technology of beauty, and the message it carries, is handed down from mother to daughter. Mother teaches daughter to apply lipstick, to shave under her arms, to bind her breasts, to wear a girdle and high-heeled shoes. Mother teaches daughter concomitantly her role, her appropriate behavior, her place. Mother teaches daughter, necessarily, the psychology which defines womanhood: a woman must be beautiful, in order to please the amorphous and amorous Him. What we have called the romantic ethos operates as vividly in 20th-century Amerika and Europe as it did in 10th-century China.

This cultural transfer of technology, role, and psychology virtually affects the emotive relationship between mother and daughter. It contributes substantially to the ambivalent love-hate dynamic of that relationship. What must the Chinese daughter/child have felt toward the mother who bound her feet? What does any daughter/child feel toward the mother who forces her to do painful things to her own body? The mother takes on the role of enforcer: she uses seduction, command, all manner of force to coerce the daughter to conform to the demands of the culture. It is because this role becomes her dominant role in the mother-daughter relationship that tensions and difficulties between mothers and daughters are so often unresolvable. The daughter who rejects the cultural norms enforced by the mother is forced to a basic rejection of her own mother, a recognition of the hatred and resentment she felt toward that mother, an alienation from mother and society so extreme that her own womanhood is denied by both. The daughter who internalizes those values and endorses those same processes is bound to repeat the teaching she was taught —her anger and resentment remain subterranean, channeled against her own female offspring as well as her mother.

Pain is an essential part of the grooming process, and that is not accidental. Plucking the eyebrows, shaving under the arms, wearing a girdle, learning to walk in high-heeled shoes, having one’s nose fixed, straightening or curling one’s hair —these things

hurt.

The pain, of course, teaches an important lesson: no price is too great, no process too repulsive, no operation too painful for the woman who would be beautiful.

The tolerance of pain and the romanticization of that tolerance begins here, in preadolescence, in socialization, and serves to prepare women for lives of childbearing, self-abnegation, and husband-pleasing. The adolescent experience of the “pain of being a woman” casts the feminine psyche into a masochistic mold and forces the adolescent to conform to a self-image which bases itself on mutilation of the body, pain happily suffered, and restricted physical mobility. It creates the masochistic personalities generally found in adult women: subservient, materialistic (since all value is placed on the body and its ornamentation), intellectually restricted, creatively impoverished. It forces women to be a sex of lesser accomplishment, weaker, as underdeveloped as any backward nation. Indeed, the effects of that prescribed relationship between women and their bodies are so extreme, so deep, so extensive, that scarcely any area of human possibility is left untouched by it.

Men, of course, like a woman who “takes care of herself. ” The male response to the woman who is made-up and bound is a learned fetish, societal in its dimensions. One need only refer to the male idealization of the bound foot and say that the same dynamic is operating here. Romance based on role differentiation, superiority based on a culturally determined and rigidly enforced inferiority, shame and guilt and fear of women and sex itself: all necessitate the perpetuation of these oppressive grooming imperatives.

The meaning of this analysis of the romantic ethos surely is clear. A first step in the process of liberation (women from their oppression, men from the unfreedom of their fetishism) is the radical redefining of the relationship between women and their bodies. The body must be freed, liberated, quite literally: from paint and girdles and all varieties of crap. Women must stop mutilating their bodies and start living in them. Perhaps the notion of beauty which will then organically emerge will be truly democratic and demonstrate a respect for human life in its infinite, and most honorable, variety.

BEAUTY HURTS

CHAPTER 7

Gynocide: The Witches

It has never yet been known that an innocent person has been punished on suspicion of witchcraft, and there is no doubt that God will never permit such a thing to happen.

Malleus Maleficarum

It would be hard to give an idea of how dark the Dark Ages actually were. “Dark” barely serves to describe the social and intellectual gloom of those centuries. The learning of the classical world was in a state of eclipse. The wealth of that same world fell into the hands of the Catholic Church and assorted monarchs, and the only democracy the landless masses of serfs knew was a democratic distribution of poverty. Disease was an even crueler exacter than the Lord of the Manor. The medieval Church did not believe that cleanliness was next to godliness. On the contrary, between the temptations of the flesh and the Kingdom of Heaven, a layer of dirt, lice, and vermin was supposed to afford protection and to ensure virtue. Since the flesh was by definition sinful, it was not to be uncovered, washed, or treated for those diseases which were God’s punishment in the first place — hence the Church’s hostility to the practice of medicine and to the search for medical knowledge. Abetted by this medieval predilection for filth and shame, successive epidemics of leprosy, epileptic convulsions, and plague decimated the population of Europe regularly. The Black Death is thought to have killed

25

percent of the entire population of Europe; two-thirds to one-half of the population of France died; in some towns every living person died; in London it is estimated that one person in ten survived:

On Sundays, after Mass, the sick came in scores, crying for help and words were all they got: You have sinned, and God is afflicting you. Thank Him: you will suffer so much the less torment in the life to come. Endure, suffer, die. Has not the Church its prayers for the dead.

1

Hunger and misery, the serf’s constant companions, may well have induced the kinds of hallucinations and hysteria which profound ignorance translated as demonic possession. Disease, social chaos, peasant insurrections, outbreaks of dancing mania (tarantism) with its accompanying mass flagellation — the Church had to explain these obvious evils. What kind of Shepherd was this whose flock was so cruelly and regularly set upon? Surely the hell-fires and eternal damnation which were vivid in the Christian imagination were modeled on daily experience, on real earth-lived life.

The Christian notion of the nature of the Devil underwent as many transformations as the snake has skins. In this evolution, natural selection played a determining role as the Church bred into its conception those deities best suited to its particular brand of dualistic theology. It is a cultural constant that the gods of one religion become the devils of the next, and the Church, intolerant of deviation in this as in all other areas, vilified the gods of those pagan religions which threatened Catholic supremacy in Europe until at least the 15th century. The pagan religions were not monotheistic and their pantheons were scarcely conservative in number. The Church had a slew of deities to dispatch and would have done so speedily had not the old gods their faithful adherents who clung to the old practices, who had local power, who had to be pacified. Accordingly, the Church did a kind of roulette and sent some gods to heaven (canonizing them) and others to hell (damning them). Especially in southern Europe the local deities, formerly housed on Olympus, were allowed to continue their traditional vocations of healing the sick and protecting the traveler. The Church often transformed the names of the gods —so as not to be embarrassed, no doubt. Apollo, for instance, became St. Apollinaris; Cupid became St. Valentine. The pagan gods were also allowed to retain their favorite haunts — shrines, trees, wells, burial grounds, now newly decorated with a cross.

But in northern Europe the old gods did not fare as well. The peoples of northern Europe were temperamentally and culturally quite different from the Latin Christians, and their religions centered around animal totemism and fertility rites. The “heathens” adhered to a primitive animism. They worshiped nature (archenemy of the Church), which was manifest in spirits who inhabited stones, rivers, and trees. In the paleolithic hunting stage, they were concerned with magical control of animals. In the later neolithic agricultural stage, fertility practices to ensure the food supply predominated.

Gynocide: The Witches

Anthropologists now believe that man’s first representation of any anthropomorphic deity is that of a horned figure who wears a stag’s head and is apparently dancing. That figure is to be found in a cavern in Ar-riege. Early religions actively worshiped animals, and in particular animals which symbolized male fertility—the bull, goat, or stag. Ecstatic dancing, feasts, sacrifice of the god or his representative (human or animal) were parts of the rites. The magician-priest-shaman became the earthly incarnation of the god-animal and apparently dressed in the skins of the sacred animal (even the Pharaoh of Egypt had an animal tail attached to his girdle). There he stood, replete with horns and hooves—the primitive deity, attributes of him echoing in the later deities Osiris, Isis, Hathor, Pan, and Janus. His worship was assimilated into the phallic worship of the northern sky-thunder-warrior gods (the influence of which can be seen in Druidic practices). These pagan rites and deities maintained their divinity in the mass psyche despite all of the Church’s attempts to blacklist them. Some kings of England were converted by the missionaries, only to revert to the old faith when the missionaries left. Others maintained two altars, one devoted to Christ, one to the horned god. The peasants never played politics—they clung to the fertility-magic beliefs. Until the 10th century, the Church protested this willful “devil worship” but could do nothing but issue proclamations, impose penances and fasts, and, of course, carry on the unending struggle against nature and the flesh.